Among the many gems of the London National Portrait Gallery’s collection is an arresting painting of the British artist Louise Jopling, made by her friend John Everett Millais in 1879. The result of five consecutive sittings – or standings, more precisely – the work, Jopling said, ‘was considered the finest woman portrait he ever painted’, despite it capturing what she initially deemed an unflattering look, unsuitable for a portrait. By her recollection, the ‘designedly beautiful expression’ she’d worked to project throughout the first two sessions lapsed during the third amidst a conversation on an unpleasant topic, and it was ‘the defiant, rather hard’ look she unconsciously, momentarily wore that Millais preserved instead. This misgiving on Jopling’s part, however, subsequently gave way to owning that the portrait conveyed something infinitely more satisfying than ‘a sugary-sweet expression’, the artist’s swift, unmediated transcription snaring an otherwise intangible impression of his sitter’s strength and substance. The Jopling of Millais’ portrait is indeed no vapid society beauty. She is forthright, steely, intelligent; the confrère of Millais and James McNeill Whistler (among others), not merely one of their subjects. She is a wife who out-earned her husband, the founder of a women-only art school, and a supporter of women’s rights.

The animating signature

by Joanna Gilmour, 21 January 2019

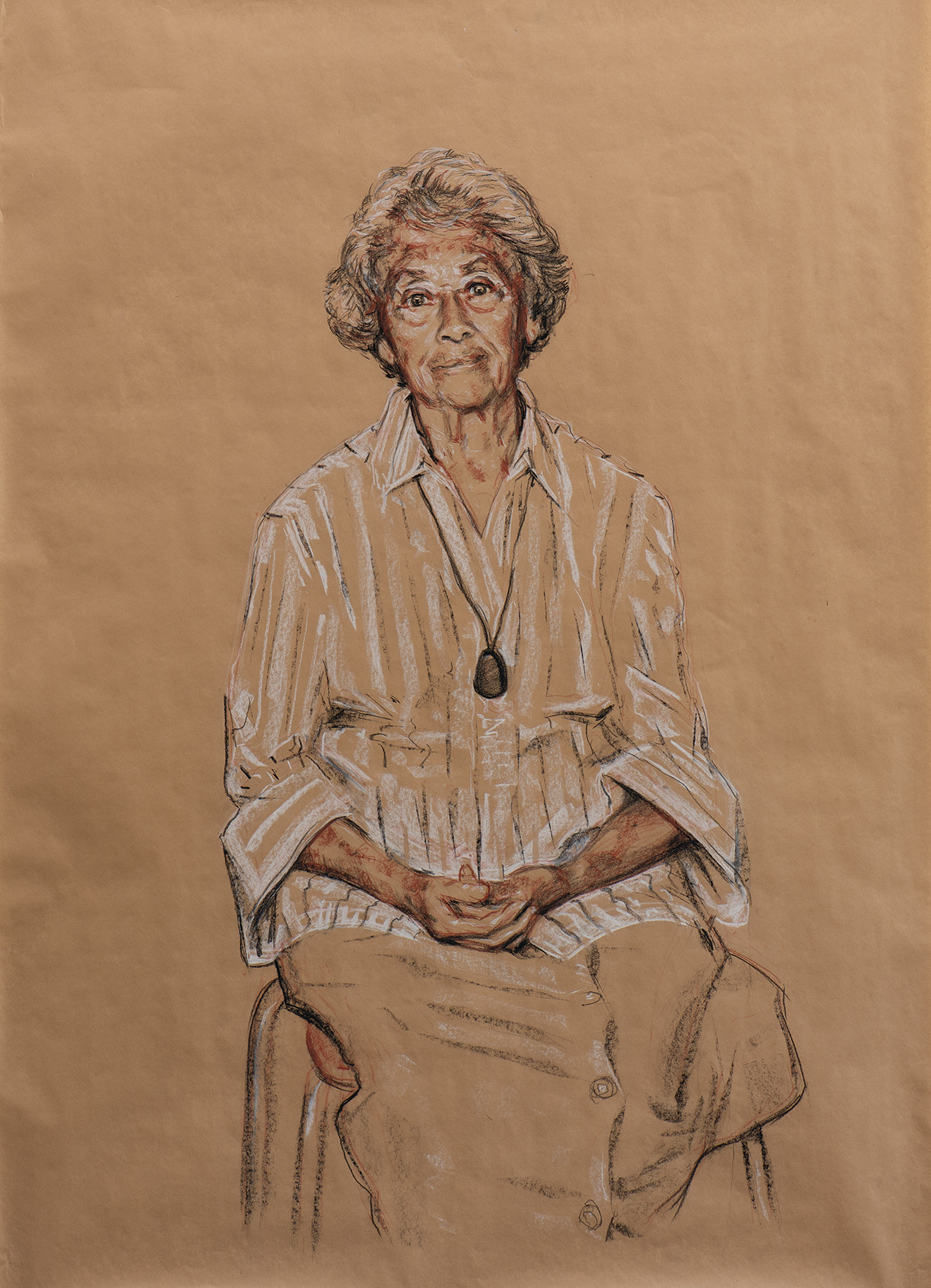

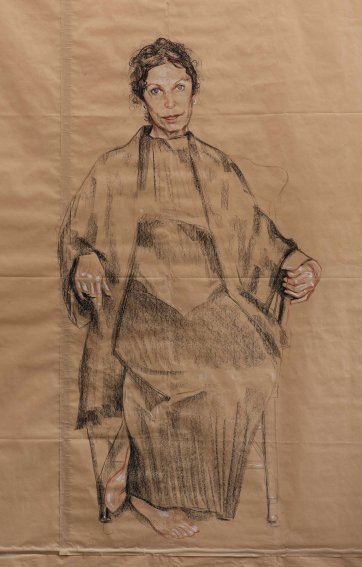

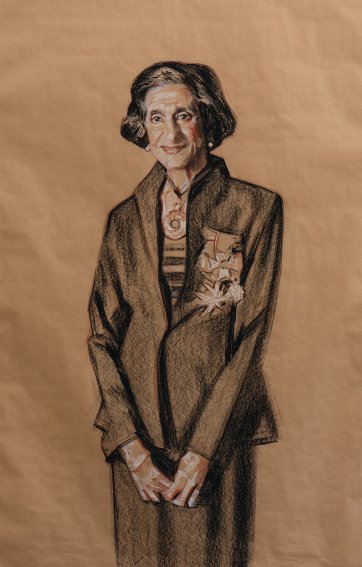

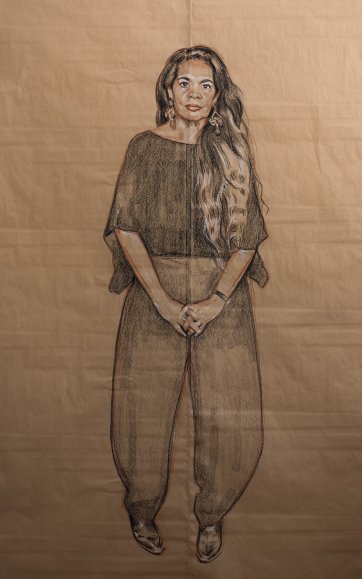

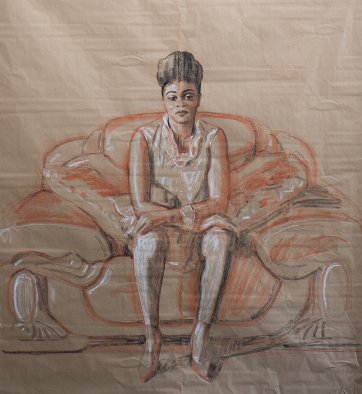

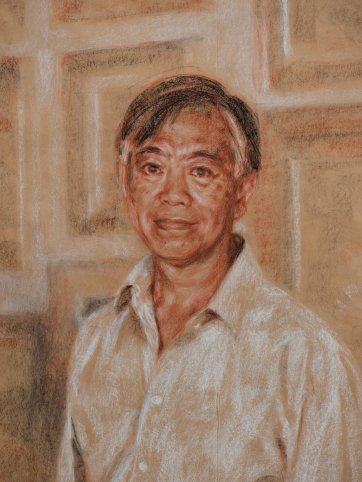

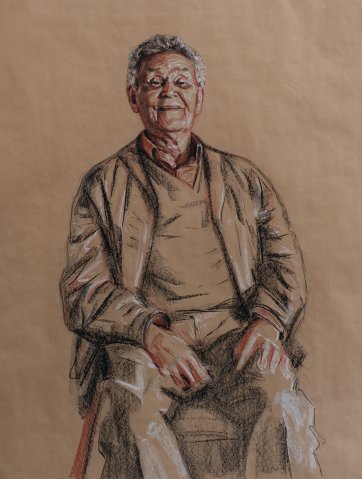

The portrait itself, then, offers a salutary example of what might ensue when an artist embraces the mystery of the ‘graphic moment’. This is a phrase Australian painter Mathew Lynn uses in reference to his process – or specifically the part played by the immediacy of drawing in capturing what he calls ‘an inner animating signature’ and the ‘immediate intuitive flash’ which guides him in the representation of his sitters. For Lynn, drawings provide the conduit to a ‘pleasing deeper rhythm’, and a direct, simple way of responding to what he senses of his subjects in the course of what might be intermittent or abbreviated sittings. Though not exclusively a portraitist – his recent output, for instance, includes a series of ineffably soothing, softly lit scenes of the escarpments near his home in the Blue Mountains – Lynn is easily one of Australia’s most distinguished and accomplished exponents of the genre. Since obtaining his master’s degree from the University of New South Wales in 1996, he’s been a finalist in the Archibald Prize fifteen times and runner-up twice (1997 and 1998), and has taken out the People’s Choice Award and Packers’ Prize. In addition, among an exhaustive list of accolades, Lynn has been a finalist for the Doug Moran National Portrait Prize, the Black Swan Prize, the Shirley Hannan National Portrait Award (which he won in 2010), as well as the Jacaranda Acquisitive Drawing Award and the Dobell and Adelaide Perry Prizes for Drawing. His sitters – some whom he is drawn to, others who commission him – include eminent curators Tony Bond, Hetti Perkins and Franchesca Cubillo; Dame Marie Bashir; AFL legend Bob Skilton; actress Anna Volska; NSW premier Gladys Berejiklian; artists Wendy Sharpe and Guan Wei; novelist and human rights advocate Tara Moss; singer David Lehā; Congolese community figure Justine Ndayi; paediatrician Dr John Yu; Blue Mountains elders Aunty Mary King and Uncle Merv Cooper; scholar and sinologist Pierre Ryckmans; and recently, for the National Portrait Gallery, businesswoman Catherine Livingstone.

Lynn has said that he creates his portraits so as to concentrate the viewer’s attention on the face, with the support of something essential in body language, using drawing as a means of capturing the ‘spark – almost like a vision’ which comes from his encounter with the sitter. Whereas Velasquez’s restrained, full-length portraits have previously been cited as Lynn’s antecedents, parallels with Millais, Whistler and contemporaries like William Merritt Chase are equally instructive. This is not because of their low-keyed palettes and minimal backgrounds that allow the sitter, as Millais put it, ‘to stand back in [their] own atmosphere behind the frame’, but because of that quick, unaffected and confident sensibility that evokes the graphic moment and the connection between artist and sitter, sitter and artist, no matter how fleeting or subtle the spark may be. The result, as reviewer John McDonald has previously explained of Lynn’s work, is ‘direct and seamless’ portraits characterised by ‘a hint of psychological penetration’ and wherein the sitters – divested of excessive symbolism or allusion and the other perceptible methods employed to communicate something of someone’s history or character – are strikingly yet quietly present, resonant and affecting. For Lynn, the portraitist’s craft is to ‘give the right entry into a persona’, and to honour ‘how the fruition of an entire life … can be written in the face and the body, without even saying anything’.

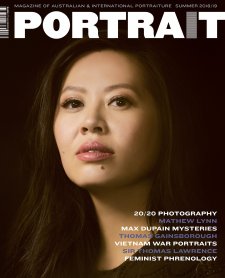

Related information

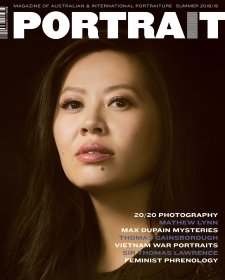

Portrait 61, Summer 2018/19

Magazine

Max Dupain's unknown portrait subjects, phrenologist Madame Sibly, Indigenous-European relationships, Thomas Gainsborough and more.

The Lawrence lustre

Magazine article by Angus Trumble

Angus Trumble salutes the glorious portraiture of Sir Thomas Lawrence.

The jungle look

Magazine article by David Gist

David Gist steps beyond the public relations veneer of Australia’s official Vietnam War portrait photographs.