There are people who think it’s perverse and unhygienic to let an animal on the bed, and would never entertain the idea. Then there are people who agree it’s perverse and unhygienic, but egg the beast on to hop up. If you didn’t need money, you could lie there for hours scratching its tummy, playing with its ears and waving its germy paws in time to ‘All You Need is Love’.

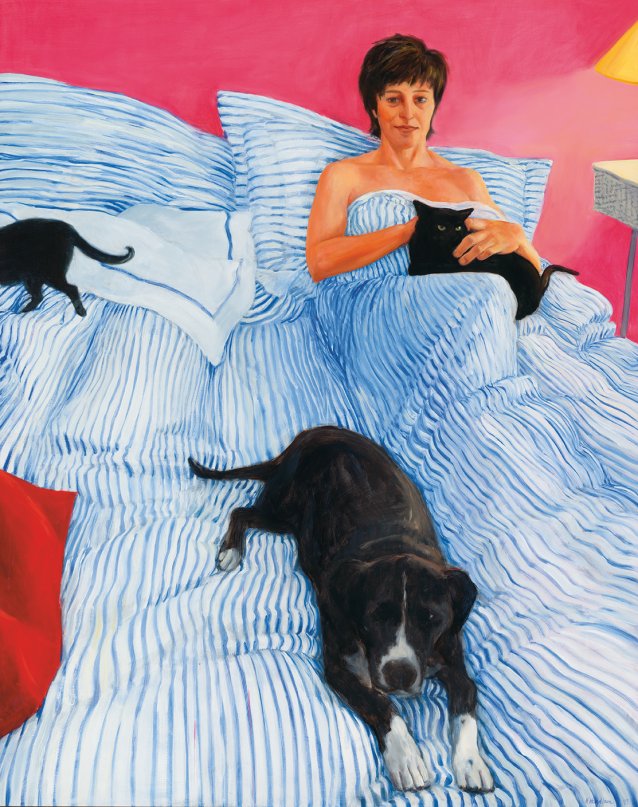

Kristin Headlam didn’t have a dog until she was forty. When she got one, from a rescue facility, she named her Dora Pamphlet and let her on the bed straight away. In 1999, the artist felt an urge to celebrate her happy hours of domestic repose in a boudoir self-portrait with a twist: she made her dog the dominant figure in the composition. It’s hard to get the eyes of a black dog right; yet by way of those eyes and the slightly lowered head, she conveyed the sense of Pamphlet’s characteristic keenness to do the right thing. The cat Hercules – a biter – was cranky, because instead of lying considerately, cosily still, Kristin kept shifting to set up the scene. His ears are flattened, and we sense his tail twitching. His mate Oscar’s intent on embodying the cliché about cats being hard to herd. To cap it all, Headlam set herself the challenge of painting a striped doona cover, which had to be made to curve convincingly over breast, hip and thigh. It all paid off when, in 2000, she took out the Doug Moran prize for portraiture. After her victory, people wrote to tell her how much they liked sleeping with their pets, too.

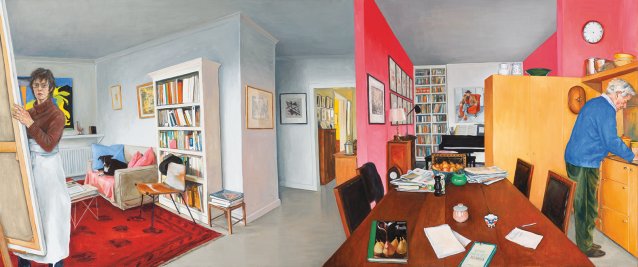

Kristin Headlam’s an observant woman with a high-wattage smile, who lives in an old house behind a solid metal security gate in one of Australia’s coolest suburbs, Brunswick. It’s not far from the University of Melbourne, long-time workplace of her partner, Chris Wallace-Crabbe. Raise the subject of cats with him and he’s likely to bring up Seamus Heaney’s translation of ‘Pangur Bán’, a ninth-century Irish poem about the shared life of a writer – probably a monk– and a white mouser. You get a good idea of the Headlam/Wallace-Crabbe home from the painting About the house: it’s got art and books and art books, comfortable sofas, a baby grand, worn Persian rugs, a big wooden kitchen table, intellectual periodicals, fresh flowers. Along a pink wall hangs an emblem of the union of literary and visual art: Headlam’s series illustrating William Blake’s thrilling poem ‘The Sick Rose’. On the back wall in About the house is a portrait of Kristin’s late father, who used to live in an attached flat. Now it’s guest accommodation, and when she’s not painting, Headlam’s likely to be getting it ready for visitors, shaking out pillows, polishing mirrors and folding towels. Otherwise, she’ll be in her two-storey studio just across from the kitchen.

Just inside the glass door of the studio, next to a sunny window, is a basket for Basil. One day in 2012, Kristin and Chris went to the Lost Dogs’ Home, and saw a puppy with almond-shaped, kohl-rimmed eyes, who sat quietly at the back of his pen while the rest of the inmates clawed at the wire. Loved from the moment they put him in the car, he grew into a speckled beauty – a long-legged leaper and an exceptionally vocal dog, with a great register of sounds, ascending in shock value from a whimper to a growl to a bark to a yelp that’s a violation of the ears. Basil steps out is his first appearance on canvas. It’s a happy picture. The position of his ears, his high back, his outthrust nose and the angle of the lead – he’s preceding Kristin – attest to his satisfaction with his neighbourhood.

Over the course of her career, Headlam’s been much more likely to paint something she’s seen than something she’s imagined; but she doesn’t have to have seen it first-hand. For example, she painted a series of wedding groups, based on clusters she’d observed in Melbourne’s fine parks. On canvas, though, the participants came out mixed with various figures she’d seen in works of art by Velazquez and Goya. It’d come as no surprise to see in one of them a flowergirl standing in the same way as, say, dear little Prince Felipe Prospero does in Velazquez’s portrait of 1659 (there’s a very lively dog in that picture, incidentally).

For years, she painted dismaying and alarming scenes she saw first in the newspapers: soldiers, refugees, the aftermath of a bomb; weightlifters, footballers, bushido fighters; European politicians, the Williams sisters, Cherie Blair; the Howards and the Rudds in dire diplomatic situations. When she stopped painting pictures of terrible events and rictus smiles, she worked through painting corners of her garden in different lights at various times of the year. Recently, in a conscious effort to peel her art away from her own environment, she’s been working hard on a series of fantastical etchings featuring monkeys, owls, foxes, tents, boats and stars, inspired by Chris Wallace-Crabbe’s ‘The Universe Looks Down’.

Headlam periodically becomes bored with one art medium and turns for relief to another. She’s invigorated by watercolour, which calls for a bold approach, yet a light touch. You can’t fiddle with it; one go at it, and the work is either made, or ready to throw away. You drop paint on; you move it around a bit, dab it a little, leave it to dry – but when you come back, it will have moved again of its own accord. Her wombat may be a miracle materialising from the combination of skill and the caprice of the watercolour. But what luck, to get the plane of the face, the solidity of shoulder and haunch; and what skill, to get the gleam in the animal’s tiny left eye! Years after her famous bedchamber painting, Headlam made an affecting watercolour of Pamphlet after she’d been treated for a haematoma of the ear. She’s isolated on the white paper, her subdued little form emphasised by the sad puddle of shadow, her disconsolate face framed by a protective contraption that vets call an ‘Elizabethan collar.’ Headlam was enchanted by the term.

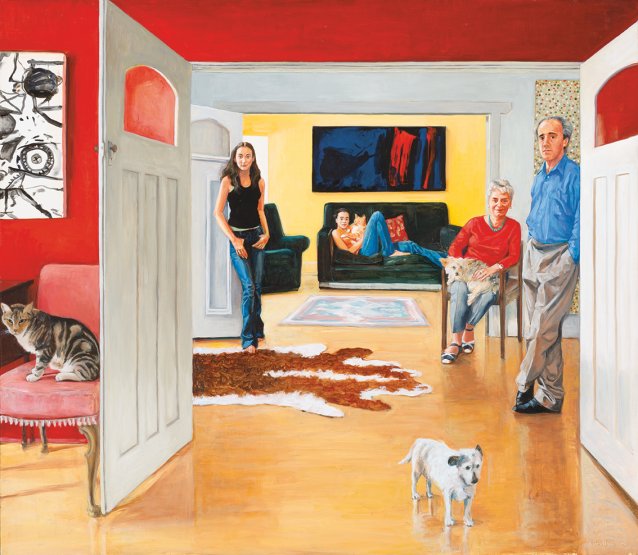

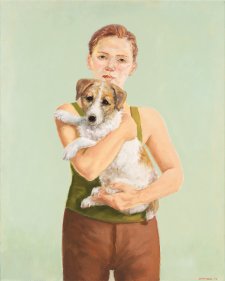

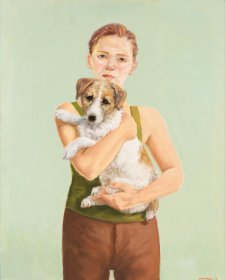

Between 2005 and 2007, Headlam made three major portraits on commission: two were set in the homes of her friends Charles Nodrum and Hermina Burns, respectively, and one in her own house. Nodrum, who’s Headlam’s courtly English-born gallerist (the new term for what used to be called an artist’s ‘dealer’), likes to refer to the dramatis personae in his commissioned family portrait. Indeed, Headlam’s constructed the picture to resemble a theatre set, its props confined to a few pieces of furniture and a mere fraction of the pictures that Charles’s amassed over his many years in the art game. The ‘actors’, though, seem transfixed by the painter, herself; they’re all looking at her (or us, if you like) very keenly. Though he has an air of casual command (and the ‘swagger portrait’ has a long history in Western art), Nodrum’s expression is diffident compared to those of the three women in his household. The elder daughter, Anna, her stance a feminised form of her father’s, projects her beauty challengingly at the older woman painter. She’s near the door; but at the same time, her toes dig in and grip the hide of the rug. We infer that while, for the most part, she’s ready to leave, she adheres to the comfort and familiarity of the household. Kate, the younger daughter, is a long way in the background, clutching her cat Honey in her arms. We read her position as Headlam’s indication that in life, Kate is yet to come forward.

In keeping with the stilted nature of the picture, the huge cat on the pink chair looks rather stylised – that is, not very real (although that said, there is a type of domestic cat that has just those sorts of stripes, called, excruciatingly, a toyger). Nodrum recalls that Max really was a cat of gargantuan size, writing that ‘he patrolled his territory with the watchful eye and rhythmic stride of the best of his kind’. Mrs Nodrum is the picture of agreeableness; she calls to mind Jacques-Louis David’s Comtesse Daru, one of the most beguilingly complacent figures in European art history. She has her hands full with Tiny, who was perpetually quivering with nerves; like all the other family members, he’s looking intently at the artist. Clearly, the one in the foreground is the senior dog; whatever else it may be, the family portrait is evidently a tribute to Emma, once tirelessly playful, now a stiff-jointed, vacant little animal, her tail down, her coat thinning, who looks fixedly at nothing.

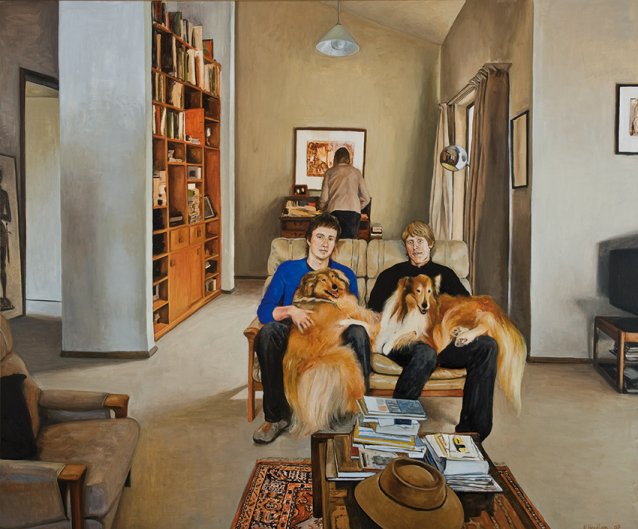

In style, the most natural of the three portraits is the painting of Andrew and David Burns with their collies, Maggie and Penny. On the table in the extreme foreground is the hat worn by their late father Graham, a literary academic. In the background is their mother Hermina, a high-school assistant principal who was effaced, at the time the portrait was painted, by grief. Elements of the elegant house are painstakingly represented, but there’s a sadness to the very light in the work. On the left side, where she could have left a void, Headlam’s included part of a brass rubbing – an impression taken from a figure on a tomb. The dead knight, the woman turned away, strike the elegiac bass chords of the painting. The lively treble is all in the dogs and the young men, whose chins sit exactly on the longitudinal halfway point of the picture. The boys’ faces are very tiny, but exquisitely painted: see the blue eyes on one, the brown on the other. The collies appear very light and rather slippery in their silky furs; they drape very gracefully, almost fishily, over the boys’ laps.

About the house was painted for the University of Queensland’s self-portrait prize, in which participation is by invitation only. The painting offers enjoyment on several levels. Most of us like a peek into other people’s houses, and here – our viewpoint high, a bit like a surveillance camera’s, with the fisheye effect intensifying that sense – we see Kristin painting; Chris making her a cup of tea; and Pamphlet, now advanced in age, observing the action from the spot on the sofa prepared for her.

Again, though, in About the house Headlam refers to Velazquez and Goya, amongst other interests and influences. She’s signed the work in a tricky way, on a note on the table, a bit like Goya signed his own name into the ground between the slippers of the Countess of Alba in his portrait of her. And she’s painted herself on the left side of the composition, behind a stretched canvas on an easel, as Velazquez did in his endlessly puzzling court portrait, Las Meninas. It’s open to anyone with an internet connection to explore that fascinating picture (the Prado’s is definitely one of 101 websites to visit before you die). One question that tantalises many of its admirers is what the painter in the picture can see on the canvas in front of him in the picture. Suffice to say that in Las Meninas, Velasquez shows himself at work on an enormous stretched canvas that seems to be about the same size as Las Meninas itself. By contrast, in About the house, Headlam works on a stretched canvas as big as she is; but the painting About the house is less than a metre in height. In other words, while Velaszquez conceivably painted himself painting Las Meninas, the painting About the house seems not to show Kristin working on About the house.

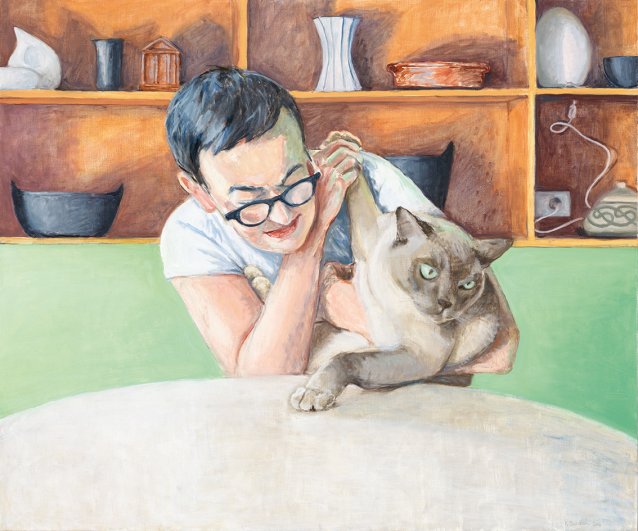

It’s not unusual for a woman to be painted in a domestic interior with a cat in her arms. It is unusual, though, for a painting of a woman with a cat to be about their tempestuous entanglement. In 2006, Kristin and her friend, the artist Louise Forthun, went together to the Lost Dogs’ home in North Melbourne. Louise had set out with modest ambitions, but amongst the ragtag alleycats at the shelter they spied a creature who looked like - and indeed was - a high-born Tonkinese: Jimmy. Kristin was insistent that he was the one and that Louise would be bagging a bargain. It’s something Kristin admits to feeling a bit rueful about, now. It seems that in his obscure infancy, Jimmy developed firm ideas about the life he was destined to lead: he grew the black heart of a hunter and nourished a wild soul. But his fate was to be de-sexed, microchipped, wormed and cherished for life. In what amounts, then, to a double portrait, Headlam has captured Jimmy in an explosive, twisted pose, back legs braced against Louise’s right arm, his big paw straining for purchase on the table and his bile-green eyes ablaze. Louise, with her left arm locked around his abdomen, seems to be checking under his arm, for a tumour or a flea; her fine eyebrows are drawn together in consternation; her lips are set in resolute benignity as she grasps the squirming beast. Jimmy has the right half of the canvas all to himself; his big head looms crossly toward the picture plane. ‘All the while his round bright eye fixes on the wall’, the scribe wrote of Pangur Bán, who had a job: extermination. Jimmy has only to purr when Louise cuddles him, but his feline integrity prevents it. Such are the complexities of interspecies and intraspecies relationships across the centuries.

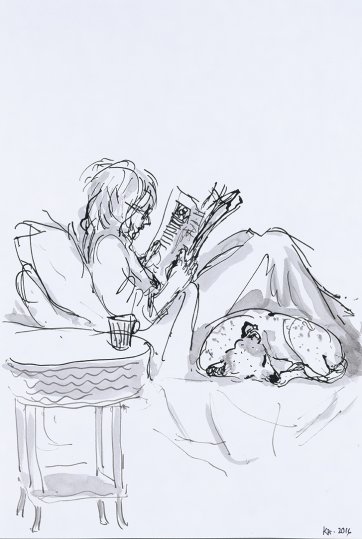

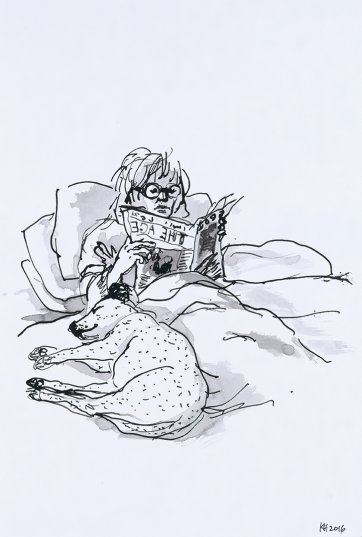

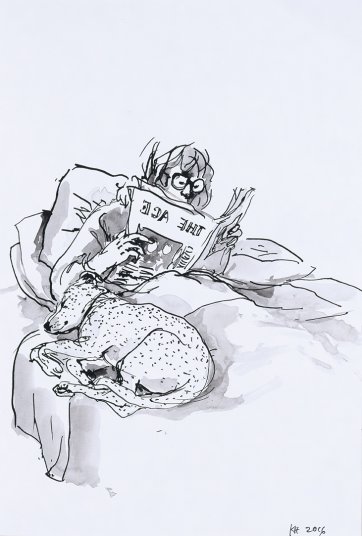

When Kristin began to draw Basil in her sketchbook, after living with him for three or four years, she began with him on the bed (a couple of drawings in the Scenes from a dog’s life were ideas for prints, which is why the typeface on the paper is reversed). The drawings, looking like New Yorker covers, started out as experiments with different ways of portraying Basil’s spots, which are diffuse, with no clear edges. By the time she painted Basil steps out, she’d worked her way to a confident treatment of his coat. Later, putting her drawings of Basil together, she saw that they’d make a nice series. Calling the four dozy morning pictures ‘aubades’, which is the term for poems that are set in the morning (John Donne’s aubade is one of the most romantic poems in English, and WH Auden’s one of the most sobering), she added a quartet of works to round out Basil’s day.

The process helped Kristin, as well as us, to get to know Basil. She knew his face by looking at him and holding his head in her hands. But it wasn’t until she painted his face that she felt, by way of her eye through her moving hand, where his ears sit on his head in relation to his eyes; whether he had a dip in the middle of his forehead, like Pamphlet did; where his spots really lay. She sees him anew, now, just as it’s open to us all to see real things in a fresh way once we’ve studied their painted representation.