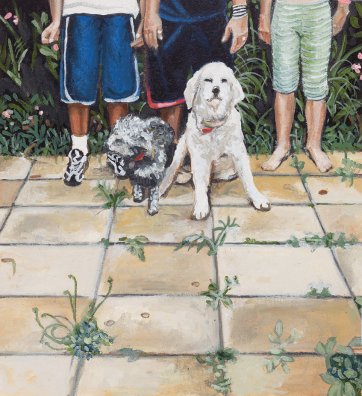

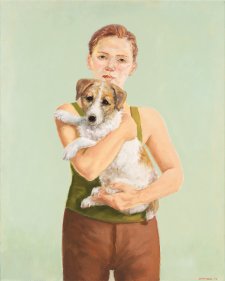

Robyn Sweaney may have painted a few dogs in their day, but by and large, she’s a house painter. Around the slumberous streets of her town of Mullumbimby, not far inland from Byron Bay in the fecund far north of New South Wales, there are a lot of small weatherboard and fibro homes. Some are nondescript, their standard of upkeep neither here nor there. A few are thrillingly dilapidated, home to hoarders or stoners, strangled by vines and squeezed along the periphery by palms, she-oaks, paperbarks. As an artist, Robyn isn’t interested in the ones that have got away. On her bike rounds in the cool of the morning, she looks out for the houses as neat as pins, maybe with a couple of scrupulously trimmed bushes, a statue or two, an arch for roses to climb. Outside the ones that tell of a battle against vegetal exuberance, she brakes. Such places find their way into her moody pictures. The only painting of Robyn’s with weeds between the pavers is one of her own three kids, posing in her own yard with the family mutts.

Robyn’s lived in Mullumbimby for decades, but she isn’t a small-town girl. She grew up in Melbourne, the daughter of an advertising man who would have preferred to be painting. They lived in the aspirational suburb of Mount Waverley, which boomed in the 1960s, in a rectangular, flat-roofed house designed by émigré architects John and Helen Holgar. They had Danish furniture, and the five children romped all over a red woollen Grant Featherstone lounge suite that eventually fell apart, unable to take any more Araldite. They had two Siamese cats; somewhere along the line there was a boxer dog called Rahni, and later two terriers, Wuff and Snuff. In spite of Snuff’s ominous name and a couple of close shaves – once, he jumped out of a moving car, and another time, on a long road trip, he was accidentally left behind at a petrol station – he outlived Wuff.

In 1978, Robyn graduated with a degree in arts and crafts, which equipped her to teach. When her first child was very little, she began painting bright jewellery and little boxes, no bigger than a pack of cards, which she sold through the Crafts Council shop. During a year in England, she charmed the inhabitants of the dark isle with their gaiety, too. In due course, the family moved to northern New South Wales, and they obtained a couple of dogs. Over ten months, by investing in a babysitter for three hours a week, she put together works for her first solo exhibition in Byron Bay; it opened when her third child, Bella, was eight months old.

When Bella was seven, her father departed. Abruptly, everything that happened in the household was Robyn’s to deal with. Thrust into a permanent reality of single parenthood, she began teaching at a local TAFE college, and working in retail, too, so she could cover the holiday periods when her income evaporated. Teddy, a tiny, scruffy terrier, was run over twice and racked up big vet bills; Seal, a golden retriever, had two litters of puppies. Eventually, in a scene straight out of a Henry Lawson story, Robyn had to dig Seal’s grave in the heavy soil of their back yard, and no matter how long she toiled at it, she just couldn’t seem to make it big enough.

It was only when her hands were full with her children, and she couldn’t paint, that Robyn Sweaney felt a passionate impulse to paint on canvas; but it took her a long time to come to terms with what to paint. Sometimes she set up still lifes of fruit on her kitchen table, and painted them in gouaches with quick, free strokes; once or twice she put her brush down and left the scene, and came back a few minutes later to find the children had raided the fruitbowl. As they got older, her kids urged her to paint, not only because they loved her but because they wanted her attention diverted from their own plans.

As she could usually neither afford materials, nor commit to prolonged projects, Sweaney’s development as an artist was a constant process of surging and halting. Any time she did spend money on equipment she felt like she was gambling; the outlay might come to nothing. A TAFE teacher in a little town, she lacked connections in the Sydney and Brisbane art scenes. She told her students that whether they put the picture out there, or put it under the bed, the trying, the doing of it, was the thing. Because she kept on painting what she could, when she could, opportunities came, in time. She entered prizes, big-city gallerists found her, group shows turned into solo shows.

She’d found a subject that absorbed her, which was her own environment, and the expression of its inhabitants’ taste in their decoration of front yards and entryways. Some people took her depictions of neat little dwellings to be critical of domesticity, in the mood of John Brack’s The new house from 1953 (which could have depicted a couple in Mount Waverley, in fact). She knows that the neatness of the façades might hint, to some viewers, of dark scenes within (even the word façade is sinister). It isn’t as if she hasn’t heard of David Lynch. But her approach is probably closer to that of Howard Arkley, who neither celebrated nor repudiated suburbia, setting out instead to get people to pay attention to the shapes and colours of structures they’d once passed obliviously.

As Robyn made more works for exhibitions and competitions, she and five other women set up an art gallery and education space in Mullumbimby; they stayed together for six years, and learning to use a computer and applying for grants were the first steps of her journey into arts administration. In 2005, the women approached the Tweed Regional Gallery in Murwillumbah with a proposal for an exhibition in which they’d ‘respond’ to works of art in its collection with works of their own. Sweaney was inspired by a playful print by Geoff Harvey, called Just Walking the Dog. In the suite of small works that eventuated, she combined elements of her developing house-painting practice with vignettes of human and canine activity in her neighbourhood. She donated two-thirds of her Walking the Dog series to Tweed, where, a few years down the track, she was to spend four years as education officer. By the time she left the gallery in 2016, to paint full-time, she’d had a dozen solo shows.

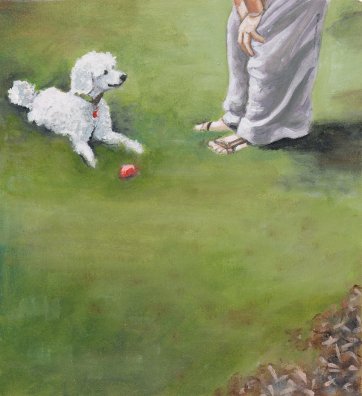

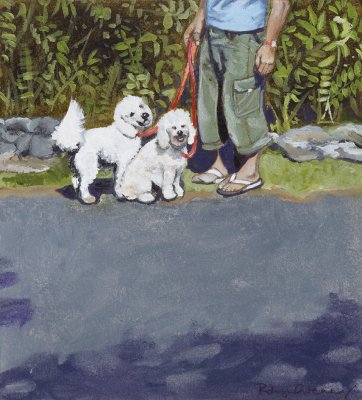

The twelve pictures in the Walking the dog suite comprise a kind of dog’s-eye view of Mullumbimby. Most of the human subjects are in open shoes, or barefoot. We can’t see faces of any of the people in them. Like a dog, the viewer looks to their thongs, slides, trainers and sandals; unlike a dog, she reads their footwear and the hems of their garments as signifiers of their ages, demographics and personalities. Robyn and her neighbours see them differently. There’s the doctor, who left his wife; his ex recoiled from the picture because the way he stands in it is so very typical (Robyn had the tact to represent his dog slinking away from him). The man in work boots was a very attractive gardener; appropriately, flowers bloom near him, and his dog gazes at him adoringly. Robyn can see it’s Jane stooping to negotiate with her perky poodle, Max, over possession of the red ball; all we know for sure is that Max intends to snatch it before she can. Plucky three-legged Hercules holds his tail aloft, for balance, perhaps. In the park, Robyn met a comfortably-upholstered woman with two Pomeranians; the dogs’ tongues matched her skirt. Knowing she was running out of people with dogs for the series, a friend encouraged Robyn to knock on a stranger’s door one morning – he was a guy who parked his car on the grass. He took a long time to come out, and when he did, still fastening his towel, she had a horrifying feeling she’d interrupted him in flagrante delicto. She stammered out the scope of her project, and he let her photograph him with Zed. Often, in her house paintings, she manipulates elements to her own purposes, moving an aerial here, a shrub there (and eliminating gnomes, which she hates to paint, these days). In this awkward case, she honoured Zed with his own numberplate.

The joy of these paintings lies not only in their invitation to compare the personalities of the dogs (note the drama of Neighbours, in which the shih tzu-type dog half in, half out of his own gate can’t wait for the terrier-type dog to move on). The joy lies in the light; in the textures of grass and asphalt; in the blurred and sharp edges of paths and roads; in the dotted areas of flowers. You can smell the air and feel the difference in temperature between glare and shadow. Fitz, sniffing at the manicured divide between grass and concrete, doesn’t seem keen to move onto the hot surface; the sun beats on the toes of his owner, in her animal-print skirt and gladiator sandals. Several of the dogs wear very broad grins – maybe too broad, in the case of the white Pomeranian (as well as the bulldogs, vectors of sociability in Sunday afternoon), but the occasional exaggeration balances the overall carefulness of the pictures. In every case, there’s the sense of life going on. Yet the shadows, too, and the fallen leaves evoke the passing of time. The artist, looking in 2016 at the works she painted in 2005, pauses over personalities who’ve evaporated. Not only most of the dogs, including her own, are dead, but some of the human figures, too; or else they’re different, disabled, gone from the town. The conversations are over.

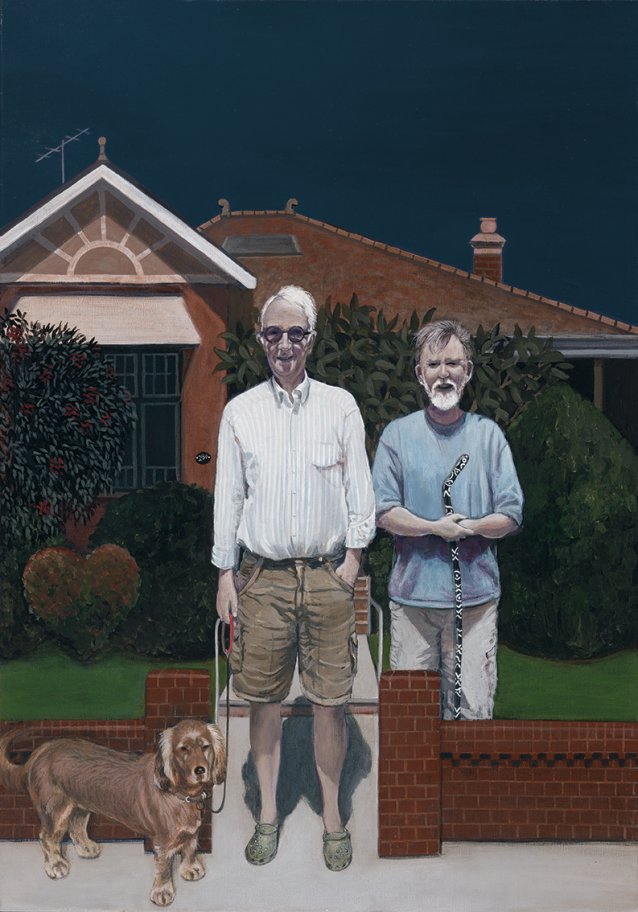

Looking from the Walking the dog series painted in 2005, to Peter Fay, Robin Evans and Milly from 2013, it’s noticeable that as she’s got older, Robyn’s paintings have become more detailed and harder-edged. Compare the shrub on the left of the painting of Peter and Robin to foliage behind the poodles Romy and Penny in the earlier series; or the finely-applied, silky fur of Milly to the gesturally-indicated pelt of Arnie. The differences show there are several ways to call attention to a painting’s ‘paintedness’; leaving visible strokes, as on the dog’s coat and the paling fence of Bronson from Walking the dog, is one way, and using tiny brushes to paint individual leaves in precise, repeated shapes is another. Robyn’s more likely to do it the second way now, partly because she has more time, but partly because of the feeling that the meticulousness of the inhabitants of the houses she represents calls for an equivalent approach from her – even if her painting arm hurts, sometimes (luckily, there are plenty of massage practitioners in the area). While the homeowners strive to create a good impression, impressionism isn’t the way to paint gardens like theirs.

Robyn struggles to pass over details, which is why she prefers weatherboard houses, and especially fibro ones, to brick ones: she’d have to paint every brick, literally counting them on the façade. And it’s always the façade – she eschews the peculiar angle, the glimpse into a comparatively untended part of the dwelling, to honour the way the owners present the front elevation. Although the Walking the dog paintings are oil on paper, these days she frequently uses artists’ acrylics, finding the new generation of such quick-drying, easily cleaned-up paints ideal for her very precise practice. She began using them because she worried about the impact of fumes of toxic solvents and oils on her children, but she found that they suited her practice of applying many layers to her works, and thinly glazing them. She never thought she’d use them, because they used to be horrible; but they evolved. Now, she says, the only disadvantage of using synthetic materials is the hint of prejudice against them persisting amidst the art world’s old guard.

As her children flew the coop, and she prepared to paint full-time, Sweaney sold her family house, and downsized to a place opposite a lush reserve a bit back from the main drag. It has a flat that she’s made into a bright studio. Her furniture’s a mixture of antiques and clean-lined pieces that could have come from her own family home in Melbourne. You can see that she prowled through the second hand shops of the region while they were still a jumble of treasure, snapping up vases from the 1940s and 50s, lamps from the 1960s, kitsch in pristine condition, dolls’ shoes, some half-funny, half-poignant paraphernalia of housewifery. On the walls are a mix of old and new paintings and prints, abstracts and airy landscapes. She’s replanting the garden, which has winter suntraps and summer shade. On the front steps are a concrete kookaburra and a wrought-iron plant stand. Friends have sometimes hinted that if she got a dog, she might meet a man, but she’s content, for now, without a partner of any species. There was a point where she opted for a break from close caring, and found she liked it, for the time being anyway. Instead, living across from the riverside path she sees people walking their dogs all day. She squirrels their images away, for future paintings. No longer part of her domestic joy and obligation, nor her heart’s balm and burden, dogs have become part of her landscape.

4 portraits

Related people

Related information

The Popular Pet Show

Previous exhibition, 2016This exhibition expresses the joy and warmth that many of us derive from our animal companions, and celebrates their trusting, unpretentious ways, with portraits of Australians and their furry, feathered and fluffy friends.

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!

Support your Portrait Gallery

We depend on your support to keep creating our programs, exhibitions, publications and building the amazing portrait collection!