With a mum who was married to a tradie, you’d think it a fair chance that the baby Jesus would have grown up with a dog in the house. The adult Jesus is often characterised as a shepherd, ministering to his flock – a responsibility that calls for a four-legged assistant. But nay! Jesus had no dog trotting beside him on his rounds, and neither did any of his disciples. There are no favourable references to dogs in the Bible. In both Old and New Testament, dogs are synonymous with vileness, snaffling the blood of Ahab, snarling over the corpse of Jezebel and returning so dependably to eat their own vomit that the atrocious habit was inscribed in the Proverbs.

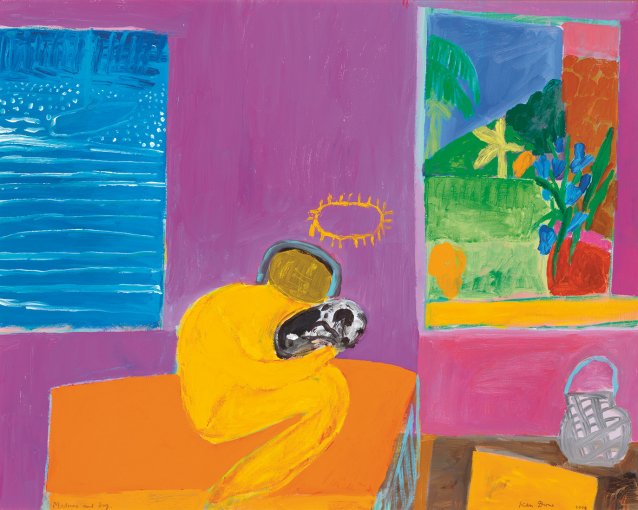

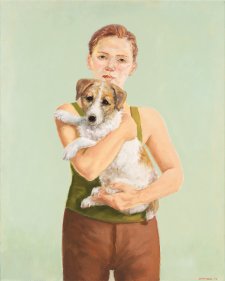

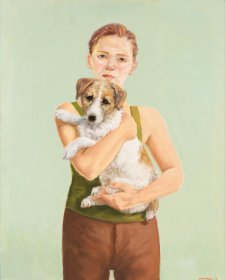

So it is that in a way, one work by the most genial and best-known of living Australian artists, Ken Done, is amongst the most blasphemous paintings in Australian art. Few if any historical paintings of the Madonna, a favourite character of Christianity and Western art alike, depict her with a dog. But in Madonna and dog, the Madonna, modelled by Ken’s wife since 1965, Judy – upon whom he’s bestowed a radiant halo – holds their dog, Spot, his curled, snoozing form proffered slightly, like an offering. Like many of Done’s works, it’s brash, cheerful and decorative; it’s also characteristic of Done’s works in that consideration of its elements, one by one, brings rewards. The body Ken’s given Judy looks to have evolved from his long study of the paintings of Henri Matisse; the colours look that way, too. As usual, Done hasn’t fussed very much over the details of Spot, but he’s captured the peaceful presence and blameless soul of the animal. In a doting, proud and protective pose, Judy tilts her head so her chin points to the yacht in the Done painting on the wall, and her left temple grazes Spot’s shoulder. A few scratches delineate her elegant brown face; her dark hair curves around her cheek to disappear down her back. It all looks so effortless and spontaneous that some might resent any scholarly considerations. Others, though, might be pleased by the suggestion that Judy’s head could have been born out of Done’s familiarity with a sculpture, made by Constantin Brâncuşi in 1910, called – non-coincidentally – Sleeping muse.

As a former advertising man, Done’s a whiz with punchlines and taglines; but its provocative title notwithstanding, Madonna and dog is only partly a joke. Done’s home on Sydney Harbour is the only church to which he belongs. As he looks at the water, the vegetation and the creatures of the harbour, he gives thanks for the life he lives. He’s a devoted parent; his family is the bedrock of his existence; his pets are family. The paintings of the great artists are his hallowed documents and relics, his hundreds of art books the texts over which he pores. It was at an exhibition of paintings by Matisse that he experienced his epiphany; a young man, then, he knew he’d seen his future. So, the painting of his wife and dog against a wall of supercharged pink and violet is a serious reflection on the profound influence of home, family and art on his imagination. It’s a deep tribute to Judy as muse and object of household worship; to the innocence of Spot; and to the glorious art of Matisse. It is funny, though.

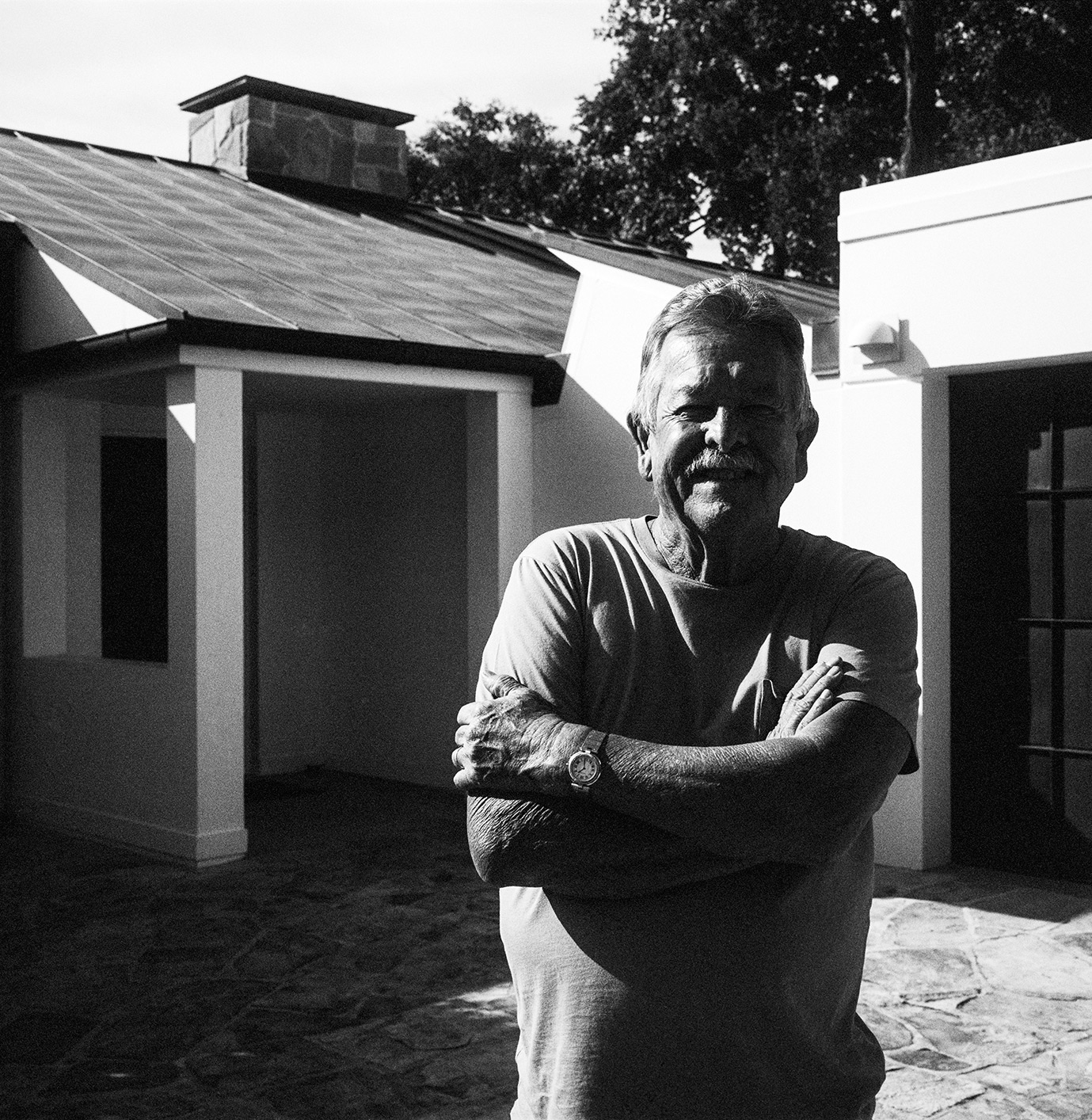

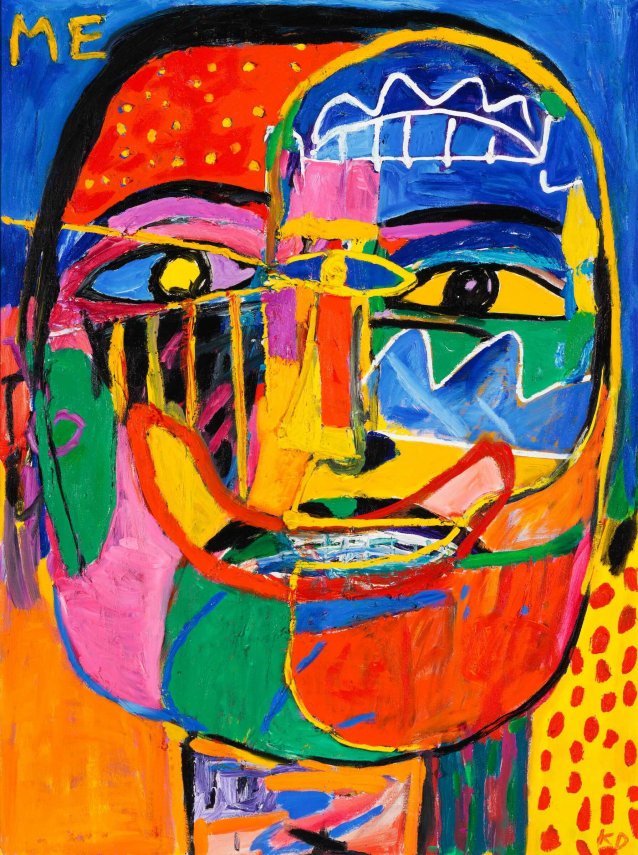

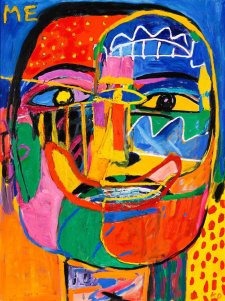

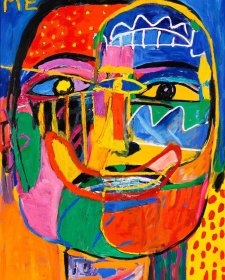

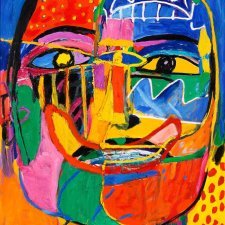

It’s no secret that Ken Done lives in a particularly attractive part of one of the world’s sparkliest cities, Sydney. The sparely-furnished home he and Judy share is literally dazzling, its glass front admitting every particle of light that blazes down and bounces up from the water and the sandstone. A stepped path winds by way of a series of terraces from the house, past the studio where he paints – looking out through one window at a strip of bushland, through another to the harbour – to a small Federation-era house (‘the Cabin’), next to Chinaman’s Beach. There are olive and orange trees in his garden, and there’s a cave, near which are carved stones commemorating his dogs, and also his parents. In this environment, Done’s painted many of the works for which he’s particularly well-known: bright, sunny pictures in blue, white, pink and yellow, dotted with yachts and bathers; seagulls; frangipani and hibiscus; ferries; the Bridge; the Opera House. That said, there, too, he’s painted drizzly days; series of Japanese submarines captured in Sydney Harbour; series arising from trips to Vietnam and Antarctica. Each Anzac Day he paints a grim black and grey canvas to honour his father, who was a bomber pilot in the Second World War. And there, he’s painted self-portraits, in different phases of life, and in varying phases of both self-analysis and painterly experimentation.

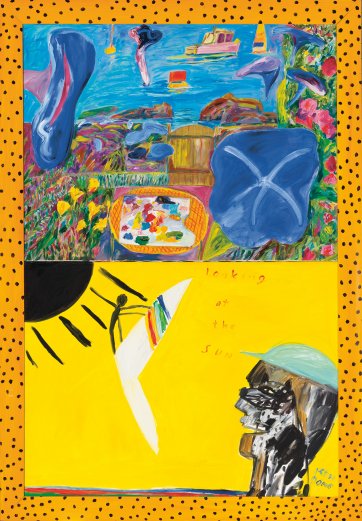

Done’s Walking the dog shows the tanned artist, smiling goofily, taking long strides in the fresh air. Spotty scurries alongside, his expression keen, his legs in a flurry. Though rotund, his shape is aerodynamic, tail in line with his back, ears flattened in the sea breeze. A few tiny white marks could be whiskers or nose hairs, but either way they enhance his endearing air of enquiry. The dynamic duo are back by the water in Looking at the sun. As Ken calls out to his son Oscar, who’s windsurfing, Spotty sits, resigned to waiting. Man and dog are so attuned to each other, they share the eye fixed on their son and brother on the water.

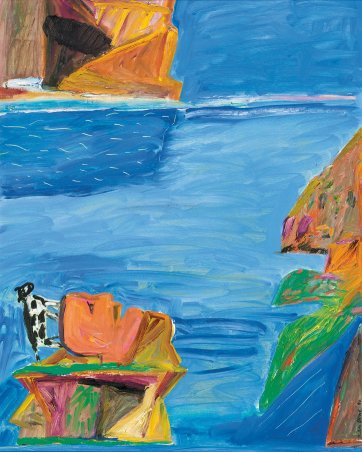

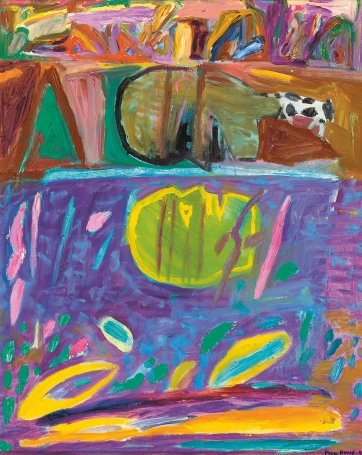

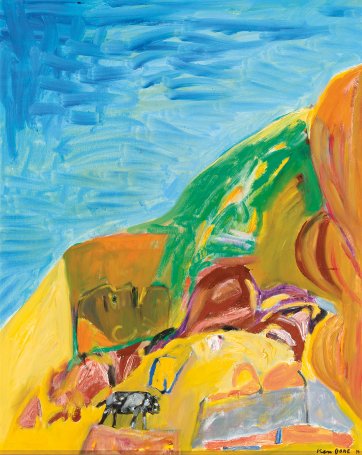

A series of four paintings conjures what it’s like to walk, thinking, with a dog off-leash. Spotty and I walking around the rocks sees Ken pacing, introspectively, as Spotty trots hither and thither. In places, Ken is so absorbed in the landscape he seems to turn into rock, himself. In the second painting the man stares at his own reflection in a pool, but he seems agonised at what he sees. (You could say he’s Narcissus’s antithesis, if it weren’t so hard to say.) Spotty trots on, insouciantly. The third is no less about Ken and Spotty and their real location on Sydney Harbour than the other works in the series. However, at the same time, it returns us to Done’s creative conversation with European artists of the early twentieth century – in this case the fauve-turned-cubist, Georges Braque. A moment online demonstrates how closely the composition of Spotty and I walking around the rocks III resembles that of Braque’s Glass on a table. The planes in the early work have become blocky rocks in Done’s picture; the dark shadow in the centre left of Braque’s painting is adapted to the dark shape of Spotty in Ken’s. At this point, the figures of Ken and Spotty merge, and we’re dismayed to see the little dog turn black, his head and tail hanging, as the man overshadows and absorbs him. After this crisis in the narrative, it’s a relief to see Spotty released from Ken and his moods, sniffing out his own business in Spotty and I IV. We might have some idea of the issues that preoccupied the middle-aged Ken in 1992. For specifics, we can consult the artist’s engaging autobiography. But what even the humblest dog knows, notices, and wonders about, remains a supreme mystery to us.

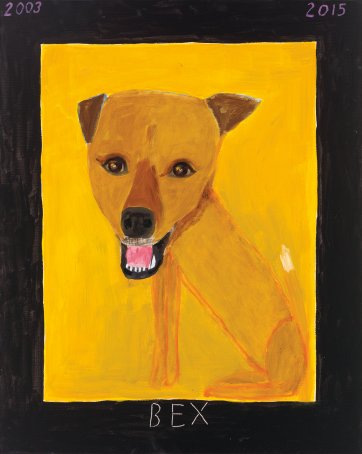

Done pays tribute to all the major dogs in his life in his series of four loving portraits. All four of the animals are cheerfully disproportionate. His own dogs Sammy and Spot ‘pose’ in his memory. To evoke the mood of looking through old photograph albums, he’s painted Samantha surrounded by an archaic oval ‘mat’, and Spot with photo corners. Samantha came into Ken’s and Judy’s lives in 1970. Ken had been thriving in London’s advertising world; in some of his major campaigns, for booze and girdles, Judy had been the photographic model. The weather got them down, though. Judy told Ken she wanted to go home and get a cocker spaniel and a baby, so they came back to Sydney. Ken resumed work. Soon, secretively, he arranged for a litter of cocker spaniel puppies to participate in a photo shoot. He invited Judy to come and watch, then told her she could take one home. That puppy grew into the barrel-chested butterball Sammy, who sits in her portrait with her feet planted apart, both ensuring stability and conveying a sense of it. A certain stolid wisdom’s implied by her crimped ear fur, recalling a judge’s wig. Not long after, the couple got Camilla, their baby. By the time the Dones got Spot, they were a human family of four, who set out excitedly in the car to get a puppy. On their first outing they ended up at a place they didn’t like the look of, and almost caused a breakout. At the second, they found Spot, who grew into the epitome of canine geniality and kept Ken company when he left the advertising world to shut himself in his studio and paint. Done’s self-portrait from 1992, now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, has one of Spot’s hairs stuck in the paint.

Sketching in the outline of Spot’s portrait in 2016, Done put his ears in the wrong place to begin with. He chose to leave the traces of them, because they convey the idea of movement, as do the smudged areas under his chin and beside his foreleg and back. His tail’s like a club, thicker at the tip than the base; but we read it as a thin tail wagging. Through all these elements, as well as the white highlights in his kohl-rimmed eyes and the smile on his dial, Ken evokes Spot’s eternal eagerness to join in. Bexley and Indi were the Dones’ granddogs, tails and ears up, tongues bared. Although Bex had a rogue lower canine that sometimes alarmed children, clearly he and Indi both were well-meaning. Only a kind man could paint such endearing mutts. In the great tradition of Done’s work, they express good things about Australia.