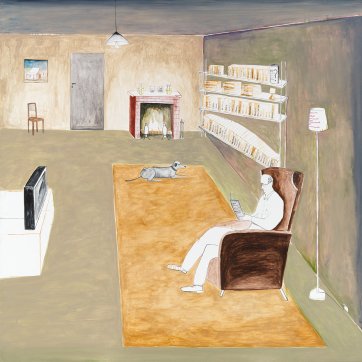

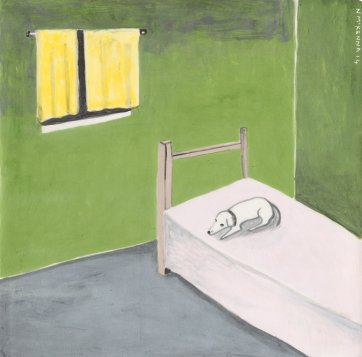

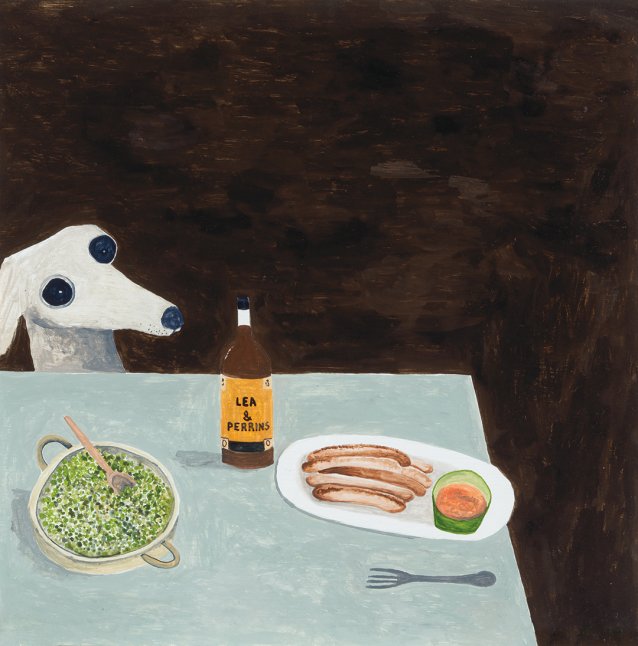

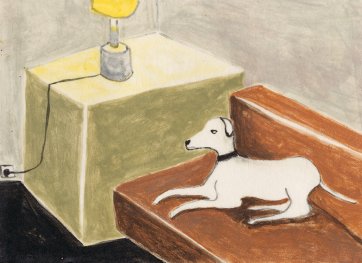

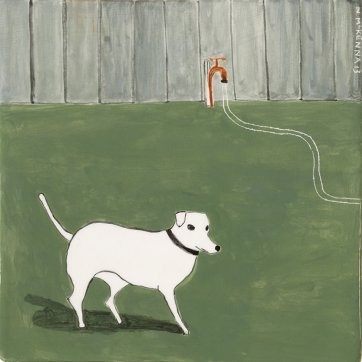

All the textiles and furnishings in Noel McKenna’s pictures are thin and mean. Look at the mustard-ochre towel in Cat at mirror, the yellow curtains and white bedspread in Dog on bed. See the blanket in Sleeping with puppy and the bookshelves, chairs and rug in Quiet room. Everything seems to have been in continuous use since the 1970s. The implied inhabitant of a characteristic McKenna scene leads a cramped, emotional life in a humble and poignantly tidy house. He allows himself the occasional tall bottle of beer with his sausages and peas; drinks tea with his fried eggs and bacon rasher; reads under a standard lamp; sleeps alone.

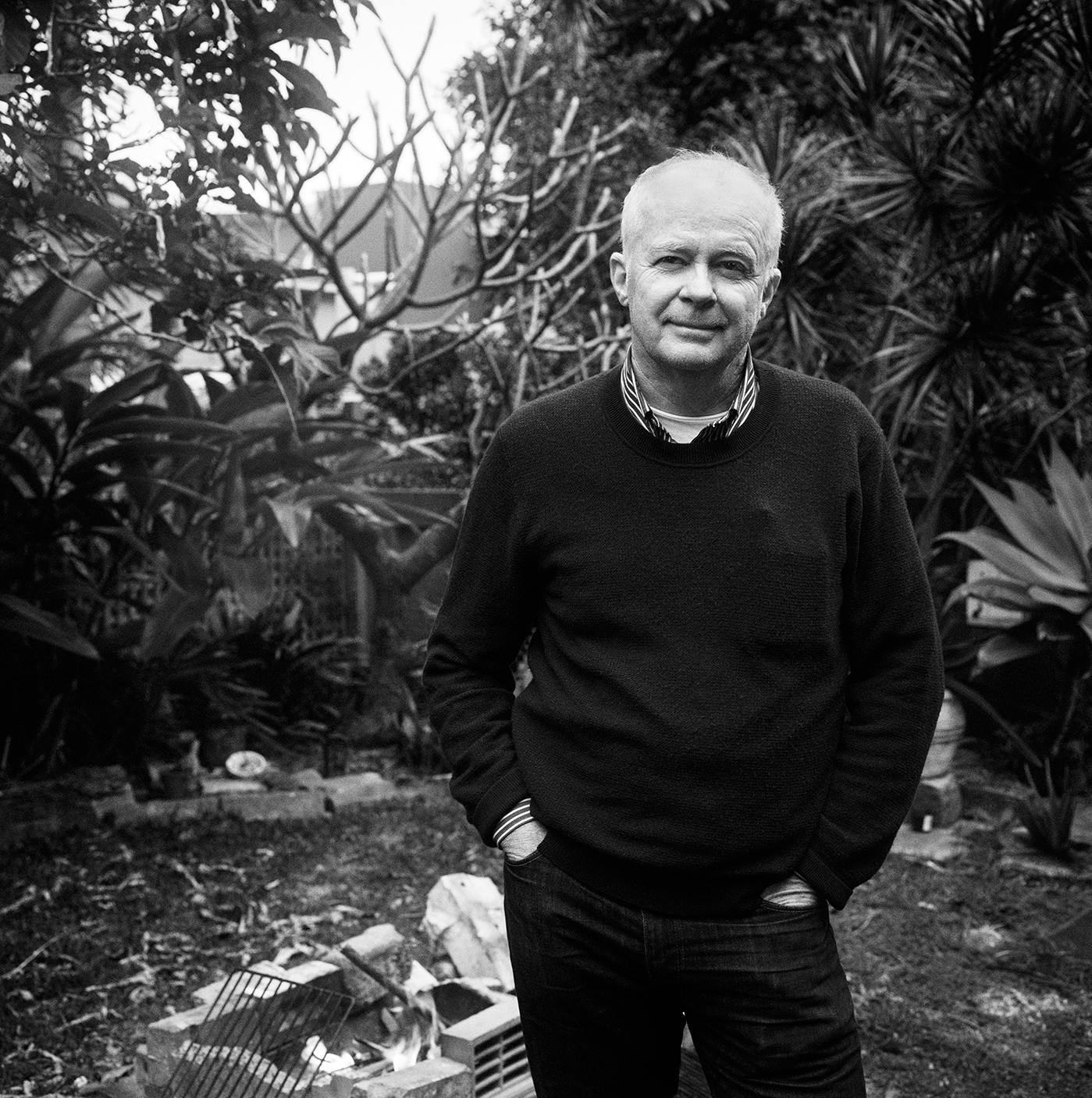

The motifs that recur in McKenna’s collected works set up the expectation that the artist himself is an ingenuous man - a loner, unworldly, an observer on the margins. Truth to tell, in appearance, he is unusually clear-skinned and wide-eyed. He doesn’t drive (then again, neither do a disproportionate number of other people involved in the arts); he corresponds in longhand; and when you open one of his letters (which are startlingly brief), little glossy photographs with white borders are apt to tumble out. He describes himself as an introvert, and some of his pictures, especially the hand-written lists and annotated maps (of, say, public toilets of the Sydney CBD), are eccentrically detailed to the point of obsession.

Noel McKenna deeply admires Joseph Cornell, a brilliant American artist who lived all his life a virgin in his mother’s meagre house; but he doesn’t lead Cornell’s kind of existence. He has a stylish, forthright wife and two fine young adult sons. Their home is in the eastern suburbs of Sydney, in a large modern house with a security gate. It’s full of the paraphernalia of family: bikes, bags, sporting gear, food, birthday cards. It’s neither minimal, nor particularly tidy. The artist’s studio is underneath, spilling across several spaces into the very capacious garage. The chaos of the studio – mostly comprising papers – astonishes even the visitor well-used to artists’ studios. McKenna’s up-to-date with events in the art world, and follows the careers of many contemporary artists. He’s a regular contestant for art prizes: he’s had works hung in the Sulman exhibition many times, and bagged the award in 1994 with a picture of his younger son dressed as Batman (he’s also won the Art Gallery of New South Wales trustees’ prize for watercolour five times). He’s represented by high-end galleries in Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide and Brisbane, as well as one in Ireland; he travels frequently, locally and overseas; at present, he’s preparing works for a show in Paris.

McKenna grew up in Brisbane, where he was educated by the Sisters of Mercy and the Christian Brothers. He studied architecture at university, but, not being very good at some of its technical aspects, switched to art school. Ray Hughes had set up as a gallerist in the city in 1969, and Philip Bacon opened his gallery five years later. In 1978 he was living impecuniously in a house a few streets up from Philip Bacon’s gallery, and he went there to see a Margaret Olley show. An imposing basket of fruit was set up in the entrance and as he left the gallery he put some mangoes and a pineapple in his bag. Philip’s mother must have seen him; she chased after him on the street, but couldn’t catch him. Whether or not the incident soured his chances of an exhibition in his home town, the artist left Brisbane for Sydney the following year. Knowing nobody in Sydney, he lived in group houses, one after another. At the time along Elizabeth Street there were old buildings divided into little offices, and he rented one to use as a studio. As the rag traders began to desert Surry Hills, he took studio space there. He went back to art school for a while; gradually, he met other artists.

On his sixtieth birthday, McKenna recalled a recent session at which he had his photograph taken with a racehorse for the Sun Herald. He confesses he’s not very good around horses; on this occasion, he clicked his tongue, and the beast pricked up his ears and pawed the ground, anticipating a run. The trainer was exasperated. Yet horses have been central to McKenna’s work from the start. His first solo exhibition was a show of etchings of the animals, at Garry Anderson’s gallery at the bottom of the Macleay Regis building in Potts Point. McKenna had a second solo exhibition with Anderson before the gallerist died of AIDS in 1990. By then the artist had married, and been signed to Bill Nuttall at Niagara in Melbourne, where he still shows. Soon he had a show at the Greenaway Gallery in Adelaide, where he also still shows, and in 1994 he had the first of his two solo exhibitions at Roslyn Oxley9 in Sydney – an assortment of horses painted on plates, with dainty dotted borders. In 1996, he went over to his current Sydney gallerist, Darren Knight.

A 1986 ‘micro-documentary’ about McKenna is viewable on the internet, along with other more recent footage of the artist. In the short film he’s painting horses – in a markedly more washy style than he uses these days, and on a large scale – and talking about how his father used to take him to the racetrack. ‘Being a painter is a bigger gamble than being a punter, in terms of getting a collect’, he observes in voiceover. Indeed, to make ends meet, he worked by night for much of the 1980s at the Cosmopolitan Café and Twenty One in Double Bay – the kinds of places beloved by locals for their club sandwiches. At thirty, McKenna spoke of how unfashionable his paintings were – yet predicted that ‘in the long term, I’ll come to the fore’. He has. Every year since 1992, on the Horses’ Birthday, 1 August, he’s painted a horsey scene in watercolours on a sheet of paper a bit bigger than A4 size. Now, the ongoing works in the 1 August series are for sale as a set. The asking price – for the completed works, plus any more McKenna might make – is about the same as tickets for a couple and their dog to spend thirty-three nights sailing on the Queen Mary II from Southampton to Fremantle, with the people occupying the top stateroom and the dog sleeping in a premium ground-level cage, having worn himself out on recreational activities planned by the ship’s kennelmaster. Art patrons’ decisions on how to deploy considerable discretionary income determine whether McKenna ‘gets a collect’ now. That said, some of his works are surprisingly affordable – because they’re surprisingly small.

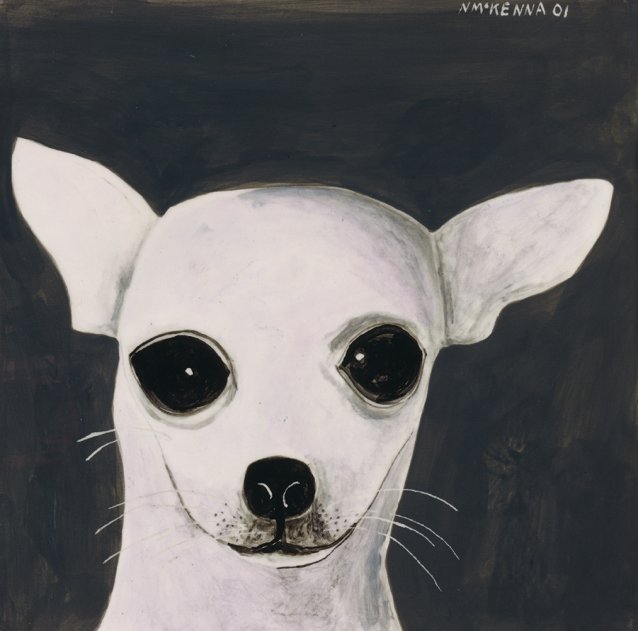

It’s a matter beyond dispute that in the entire history of Australian art, it’s Noel McKenna who’s painted the liveliest rendition of the head of a Chihuahua. McKenna turned his attention to the tiny beast in 2001, and with the smile on its dial, its glistening protuberant eyes and its thin wings of ears, it may be the only Chihuahua painted on a 20 x 20 cm ceramic tile in the world.

The artist started working on ceramics in 1993 – a time when there was a craze for paint-it-yourself ceramics. As he walked around Newtown,he spotted a place where you could select a blank white plate or jug from a range on offer, and decorate it under guidance. The first time he ventured in, he sat painting meekly while the female proprietor gave him instructions, telling him he was leaving the paint too thin. As it transpired, he was to go there for years, catching a couple of trains from Bondi, where he lived at the time. It was mostly women who went; he recalls that they sat around a big table and ‘gossiped’ as they painted. He sat in a corner, painting literally hundreds of plates and jugs, leaving them to be fired at the store and picking them up a week or so later. About ten years after he painted his first plate – a horse leaping in the middle, a delicate embellishment around the perimeter – he bought his own kiln, and now he paints his blanks in his own studio. Innumerable tiles hang around his home, and cluster in the homes of his devoted collectors. One of them says he started amassing McKenna’s tiles because he was able to hang them in his bathroom, the only place in the house where there was room for more art.

In the course of discussing his own plates, McKenna mentions Eric Ravilious, an English watercolourist who was employed by Wedgwood to decorate crockery in the 1930s. Until a few years ago, Ravilious’s work was regarded in the English art world as rather lightweight, the stuff of Christmas cards and book illustrations, an ‘escape to simplicity’. Come 2011, however, Paul Laity could write in the Guardian that Ravilious’s paintings ‘are never cosy and never merely pretty or tasteful . . . they are a strange combination of bleak, odd and enchanting’. Laity’s is an observation that applies equally to McKenna’s productions. There are certainly affinities between some of McKenna’s paintings and some of Ravilious’s – for example, the English artist’s well-known pictures Train landscape 1940 and The bedstead 1938, and his Friesian bull of 1935. Ravilious’s Westbury horse 1939 even has a googly eye just like McKenna’s Dog at dinner table, whose thin snout elevates as he detects fumes of bacon (that said, McKenna’s own dog, Rosie, has pretty bug-eyes too, and greyhounds, such as his former racing dog, Melman, are renowned for them).

Many of McKenna’s works are humorous and forlorn at the same time. The viewer who laughs outright at a painting might be reproved, gently, by the artist for not noticing it’s sad, if only by implication. In the 1990s, he put together a well-known series of paintings of posters publicising lost pets. People used to collect the posters for him. He says he still has piles of them in the studio, and looking at the studio that’s easy to believe. (It must be one of the most significant collections of old papers and miscellaneous magazines in the country; although Noel says he knows where everything is, for the visitor, even the kiln is hard to find.) A lost-pet notice wrings the heart of any pet owner. However, a work of art that is a straightforward transcription of such a poster - the lost animal drawn by McKenna from its photograph and the accompanying information copied faithfully down - is more amusing than sad. The situation depicted isn’t funny; the idiosyncratic enterprise of the artist is. Noel tells the story of one such painting, of a lost puppy; as usual, he’d included a phone number. Someone asked him why he’d chosen to inscribe Martin Sharp’s phone number on the painting, assuming, probably, that it was some sort of in-joke. It wasn’t; it turned out the artist Martin Sharp had lost his pup, and put up the ad, and McKenna had simply copied it detail for detail, as he always did. He still has the work, which is now a rather poignant artefact of Sydney’s art history.

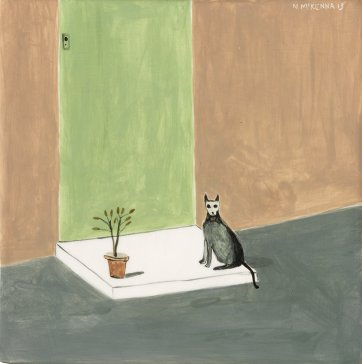

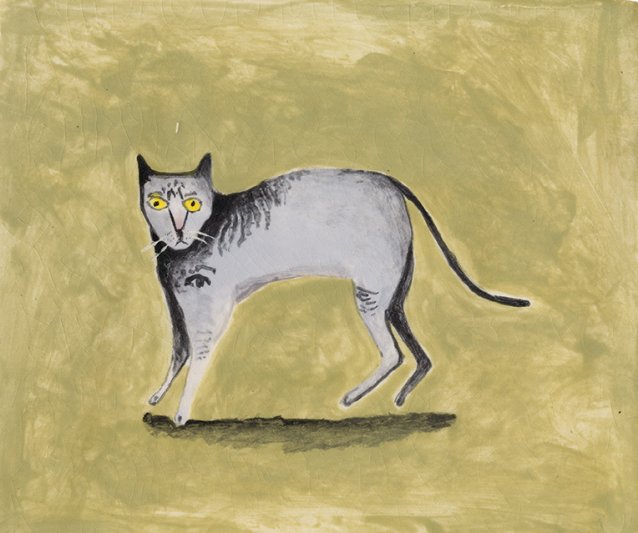

No one has ever painted a cat – an animal renowned for grace –in such a ridiculous position or at such amusing scale as McKenna has in Cat surprised. The jury’s out on whether video compilations of cats alarmed by cucumbers are funny. By contrast, Cat surprised is a licence to laugh; only the cat’s back legs are off the ground, indicating surprise, as the title makes clear, not terror. McKenna loves cats, finding them mysterious, with their own ways. When he lived in Brisbane as a boy he tried to tame a few wild ones; he used to save scraps for them, buy tins of food with the money he made on his paper round, bring kittens home. In an upper stratum of the archaeological site of his studio is Rolf Harris’s Picture Book of Cats, on the cover of which a grinning Harris, in a floral shirt, clutches a young Burmese whose eyes are practically popping out of his skull. Once just kitsch, now creepy, it’s grist for the mill of the artist, who takes a lot of his subject matter from printed materials. If you think that Girl and cat, say, has a bit of a sixties air about it, you could be on to something; he may have sourced the image from an old book, magazine or record cover.

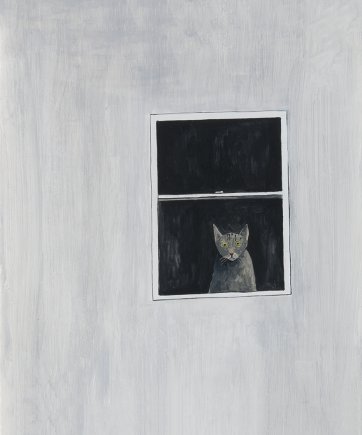

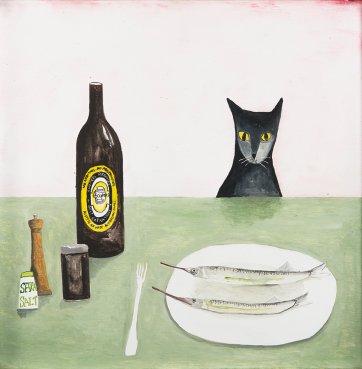

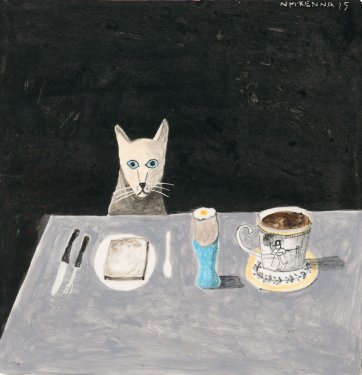

Girl and cat is very unusual, amongst McKenna’s works, in both its close perspective and its female subject. It’s droll because the cat has its forelegs pinned by the girl’s arm, and because of the similar expression of ennui in their four big eyes. The cat on tippy-toes in Cat at mirror was taken from a run-of-the-mill cat picture on the internet. The artist added the animal’s scrawny legs, the counterbalance of the tail, and the archaic sink; we chuckle at having caught the cat looking at itself crossly. The big window frame in Cat inside looking at me emphasises the tiny head of the animal, an offended expression on his face. The wide-eyed Cat at table’s transfixed by the garfish on the plate, but its right ear swivels slightly, as if it’s gauging the risk of hopping up to nab the meal. By contrast, the cat in the tile Cat at table has a faraway look, as if it intended to explore the possibilities of the table but then started thinking of some bigger issue in its life.

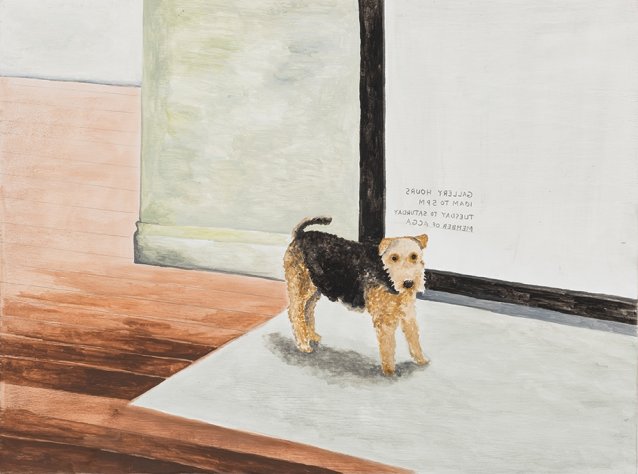

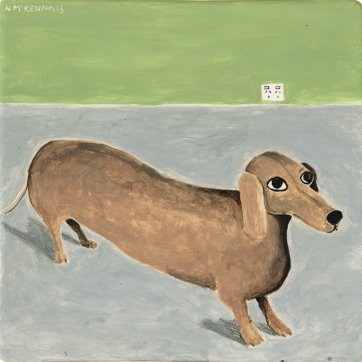

McKenna’s done a few commissioned pictures of dogs, including his Brisbane gallerist Bruce Heiser’s imperious Asta of Annerley, but he’ll only undertake the commission if he likes the dog. Apart from Asta, who appears to be posing very regally for his portrait, adopting an expression of disdain, all the animals in his pictures seem to have been caught unawares. Sometimes they’re just brooding, like Dog on back step, who’s like a dumb teenage jock, devoid of original thought, awaiting a game. Sitting room’s little greyhound, lying in a similar position on the settee, seems the wilier of the two. Like a lot of McKenna’s animals, he doesn’t have defined feet. The three-legged dog hops jauntily across the lawn, tail aloft; again, like a lot of McKenna’s animals, he has sticklike legs.

So does the dog in Quiet room, a painting that brings together many of the enigmatic aspects of McKenna’s work – indeed, unusually, the question mark on the vessel on the top shelf draws attention to the indeterminacy of the scene. From a distance, the picture suggests loneliness; the closed door looks like the punctum, the little detail of a picture that makes us the saddest. The all-white, bespectacled man is a cipher; the dearth of furniture points to the infrequency of visitors. Although the signifiers of cosiness are there, in the form of packed bookshelves and fireplace, the attenuated room looks chilly. And yet . . . a close look discloses the titles of the ‘books’ (which, as is usual with McKenna’s books, look more like box folders); they’re the names of artists he could reasonably be assumed to admire. On the mantelpiece are Iittala Aalto vases and a photograph with two people in it. The man alone is reading about conversations, at least. Things are looking up, then; and at last, the painting provokes a smile, because the dog is lying in a Sphinx pose in the reverse direction to the man, looking intently at the wall, in a silly position too far from either man or fireplace. Books and art mean nothing to him.

On his travels in Finland, looking at structures by Alvar Aalto, McKenna developed a taste for saunas. On his return to Sydney, he found that the city’s amenities weren’t for him, so he had one installed in his studio space. He goes in there a couple of times a week. Just near the wooden booth, separated by piles of books and papers, is a fish tank that only has guppies in it. Noel likes them, commenting that they’re easygoing little fish. You might say that a man who declares a fondness for guppies is taking his predilection for the ordinary and unremarked to extremes. Then again, it wouldn’t be surprising if guppies proved to be the next big thing; like the tender-yet-stark, nostalgic-yet-unsentimental works of the once-unfashionable artist, they may ‘come to the fore’. It wouldn’t be the first time McKenna had been stealthily on-trend.

9 portraits

Related people

Related information

The Popular Pet Show

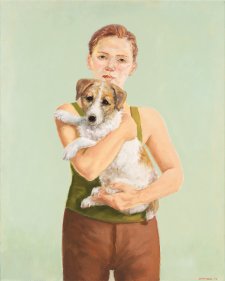

Previous exhibition, 2016This exhibition expresses the joy and warmth that many of us derive from our animal companions, and celebrates their trusting, unpretentious ways, with portraits of Australians and their furry, feathered and fluffy friends.

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!

Support your Portrait Gallery

We depend on your support to keep creating our programs, exhibitions, publications and building the amazing portrait collection!