Standing by a window with a child, we point to a kangaroo outside and brightly ask ‘What’s that?’ If they don’t say ‘A kangaroo’, we tell them that’s what it is. Going around a gallery with a child, we point to a painting of a dog and brightly ask ‘What’s that?’ If they don’t say ‘A dog’, we tell them that’s what it is. We don’t say it’s a shape inscribed by an artist that’s popularly understood to signify a dog. That’d only serve to foster a smarty-pants. As we get older, we accept, mostly, that the old way of seeing things won’t do; but a lot of us still look at art as if it’s only there to point to some reality beyond it.

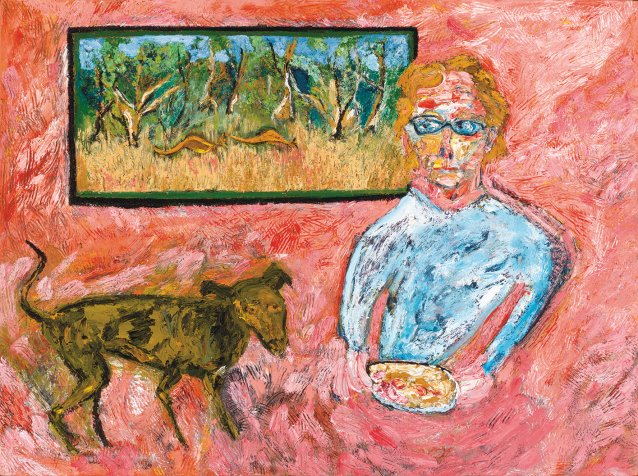

As a Brisbane schoolgirl, Davida Allen covered her naked body in paint and rolled around to make art. She still loves the smell of oil paint, and she’s keener than ever to put her bare hands in it. She’s an intensely personal painter, her subjects including what she sees while bushwalking, her yearnings and imaginings, her grandchildren. In 1986 she won the Archibald Prize with a portrait of her tetchy-looking, shirtless father-in-law. Yet her luxuriation in her medium underpins most of her paintings, which have a marked quality of materiality.

Coming to Kangaroos as a substantial object bearing symbols inviting interpretation, the viewer identifies a human torso, its bespectacled head slightly more feminine in appearance than masculine, which floats in a pink ground. Conventional signs for floor, wall, furniture are absent, yet he infers an interior scene because in the upper half of the canvas he encounters a painting of the bush on a blue day, two logo-like ‘kangaroo’ shapes in front of a cluster of tree-symbols. The figure’s ‘arms’ are short and stiff, there are no certain markers of shoulders or elbows, the ‘hands’ are simply flurries of pink. Between them is a disc toward which a happy-dog-shape, ‘tail’ aloft, is oriented. Processing these painted symbols into characters, he attempts to build a narrative, but comes up short.