The only living Australian artist who could plausibly be said to be a household name in this country, Ken Done AM, recently made a gift of two striking paintings to the National Portrait Gallery. The first is his spare and restrained representation of his friend, the Pritzker Prize-winning architect Glenn Murcutt. The second, a self-portrait in Done’s customarily riotous palette, is the first cubist-style portrait to come into the collection.

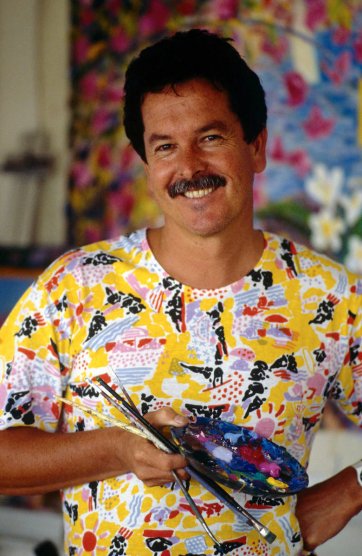

Born in 1940, Done spent much of his childhood in the New South Wales town of Maclean on the Clarence River. As a teenager, he spent nearly five years at art school in Sydney. Snaffled by an advertising agency in 1959, he soon worked his way into a position with marketing giant J Walter Thompson in London, winning a Cannes Gold Lion in 1967 for a campaign for Campari. Having painted ‘all the time’ for many years, at the age of forty he renounced his profession to focus on his art, setting himself up in a studio beneath his house overlooking Chinaman’s Beach on Sydney’s lower north shore. Soon, as the father in him came to terms with the need for regular income, the marketing man in him reasserted himself. His wife Judy became his business partner and product adviser, and before long his stylised, colourful representations of Sydney’s beaches, harbour, animals and flowers bloomed and proliferated on bikinis, bibs and vases. By 1987, when Rennie Ellis photographed Done in one of his own t-shirts against the backdrop of one of his large, vivid canvases, Done had an annual turnover of several million dollars.

In the Bicentennial year, when Australians were urged to join in the ‘celebration of a nation’, Done’s brash, naïf iconography was a perfect fit with the mood that was officially encouraged. In an article about the branding of Sydney in the 1980s, cultural commentator Susie Khamis outlines how the Australian Bicentennial Authority used Done’s services for particular items and occasions – such as the Australian Pavilion at Expo ’88 – while other designers ‘drew liberally from the Done style’. Either way, she writes, ‘1988 saw the almost panoramic influence of the Done brand’. Further, Khamis links the extraordinary success of Done’s bright merchandise to Sydney’s rapid rise, between 1985 and 1990, to a holiday destination with international pulling power. Indeed, in 1992, a mere twelve years after he had first exhibited his art and painted a dozen t-shirts to promote the show to the press, Done was made a Member of the Order of Australia for tripartite services: to art, design and tourism. The following year, he was named Australia’s Goodwill Ambassador to UNICEF.

Done’s instantly-identifiable branded products are marketed as Done Designs. His paintings, which are rather less well-known, provide the creative source of those products. In contrast to any number of artists – Monet and Van Gogh being but two – whose works have been posthumously appropriated for mugs, mouse-mats and calendars without the creator’s deriving any personal benefit, Done’s art has evolved in parallel with his merchandise in his own lifetime. Of crucial importance to Done is that the income he has derived from Done Designs has enabled him to pursue his determination to develop as a painter.

Ken Done not only acknowledges, but candidly quotes, his artistic influences – including Henri Matisse, Pierre Bonnard and David Hockney – by incorporating their names into details of his paintings, such as Long View of the Cabin I 1992 showing monographs on the three artists stacked on a shelf, or titles of his works, such as Lunch with Bonnard I 1994. Some years ago he told George Negus that he was quite susceptible to sneers at the ‘derivative’ nature of his ‘commercial’ art. ‘I’d be tougher than I really am if I told you that it didn’t hurt sometimes’, he said. After nearly three decades, the body of painting Done has amassed since 1980 can be seen as a visual diary of his immersion in the output of successive artists; his paintings tell the story of how he has come to see his own lived world through the colours and forms of his international predecessors. Terence Measham, former Director of Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum, has suggested that ‘the subject of [Done’s] art is not just the life that he lives, but also it is the art that he likes’. In Australia Done has exhibited at several well-respected galleries, including the late Judith Behan’s Chapman Gallery in Canberra and Philip Bacon’s elegant space in Brisbane. He has held scores of solo shows, many of them abroad. Yet relatively few dealers have sought to represent him. The simplest explanation is that the commercial arm of his practice has enabled him to afford to exhibit and sell his own paintings in his own harbour-side gallery – which, in turn, has shackled him to Sydney, the subject of so many of his works. Although his designs are no longer ubiquitous, as they were in the 1980s, his business remains robust and his paintings still sell well, particularly in Japan, where his instinct for colour, pattern and composition was discerned from the outset.

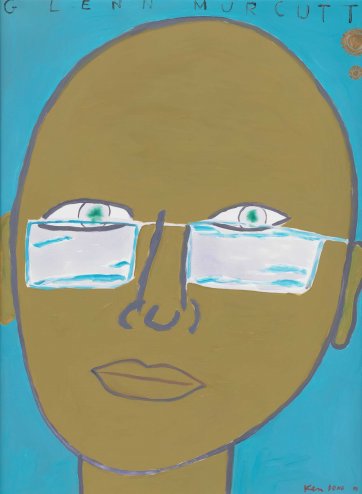

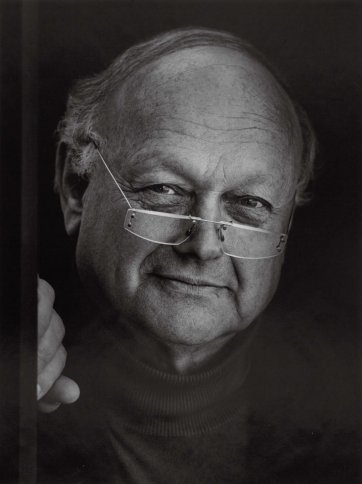

Done has painted a number of portraits, of himself, of friends and of figures he admires. He has been an Archibald finalist four times and has also been the subject of portraits by three other artists, which were hung in the Archibald exhibitions of 1992, 2000 and 2009. The two portraits acquired by the National Portrait Gallery were both painted in 1992. One, an Archibald finalist, is a portrait of the architect Glenn Murcutt, who has worked on two house projects for Ken and Judy Done. In 1992 Murcutt won the Alvar Aalto Prize from Finland as well as the Gold Medal of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects; his Pritzker Prize, the world’s pre-eminent architectural award, came ten years later. Keen for the portrait of Murcutt to accord with the personal style of his khaki-clad sitter (he says wryly that the top of his friend’s head reminds him of the curve of a typical Murcutt roof), Done kept the work very simple. The details of the architect’s face are reduced to lidless and browless eyes, nose and lips; the water is reflected in his signature half-spectacles. Floating in the blue sky over his head are the sun and moon, which sit beneath the architect’s name like golden medals or seals.

Done’s self-portrait is a more complicated work, in clashing hues of yellow, red, electric blue, cobalt and forest green. There are spots and stripes; the nose is a cord of yellow paint extruded straight from the tube. A particularly unusual feature of the portrait is its three multicoloured non-matching eyes: one pink, blue and yellow, one yellow and black, and one blue with a yellow centre. Close inspection of the eye on the right discloses an animal hair trapped in the thick paint. Probably shed from a paintbrush, it just might be a relic of Spot, the much-loved mutt who appears in some of Done’s most charming paintings, notably Spotty and I walking around the rocks I-IV 1992. Like the dirt and dog hairs that adhere to some Central Desert canvases, it reminds us that paintings are created in a defined place, in a particular personal context – in this case the harbour-side ‘Cabin’, occupied, for much of the time, by only Done, painting doggedly, and his pet, who would bark twice, says the artist, if the canvas turned out well.

The three eyes are portals to the cubist character of the self portrait, in which Done has merged a profile with a full face representation. Although he has painted his trademark moustache only once, two smiles traverse it, one in full face, a red banana shape, and one in profile, its yellow outlines loosely containing a few slashes of white teeth. Securing the picture a place amongst icons of Australian cubist portraiture are the Opera House on Done’s left cheek, and the Harbour Bridge on his forehead, like a set of patriotic wrinkles. The Opera House has been a boon for Done. Many artists have painted the harbour, but none has depicted the Opera House as he has. He says ‘I’ve drawn [it] straight. I’ve painted it in white, yellow, blue, pink, magenta, emerald, turquoise…purple and black. I’ve painted it soft, hard edged, ethereal, misty, blatant and bold. Upside-down, sideways and inside out.’

The degree to which Done personally identifies with the Opera House and the Bridge is indicated in the title of this self portrait, which is Me. Yet the straightforward title of the work belies its more complicated intention. The style and technique are both a blend and a radical extension of the approaches Done took to previous self portraits, including the stripy profile in Meeting Michael Jagamarra Nelson 1989 and the full face in Thinking about what to paint 1990. Done describes Me as at least in part a painting about the difficulty of painting, and there is a feeling of contemplation, wariness or watchfulness about the man in the portrait that he produced. Showing two Dones at once, or two perspectives on one Done, it can be interpreted as a painting that examines how what a person is famous for entangles and intersects with, overlaps and obscures who he is, who he wants to be, or what he would like to be remembered for.