Christmas Island

This is my last Trumbology before, in a little more than a week from now, I pass to my successor Karen Quinlan the precious baton of the Directorship of the National Portrait Gallery.

Stubbs and the horse

One of the chief aims of George Stubbs, 1724–1806, the late Judy Egerton’s great 1984–85 exhibition at the Tate Gallery was to provide an eloquent rebuttal to Josiah Wedgwood’s famous remark of 1780: “Noboby suspects Mr Stubs [sic] of painting anything but horses & lions, or dogs & tigers.”

The Thyssen Art Macabre

Books seldom make me angry but this one did. At first, I was powerfully struck by the uncanny parallels that existed between the Mellons of Pittsburgh and the Thyssens of the Ruhr through the same period, essentially the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

The Black Death

The best horror stories are real. A flea sinks its proboscis into the skin of a sick black rat, feeds on its blood, and ingests lethally multiplying bacteria.

The personal and the historical

Where do we draw a line between the personal and the historical? Although she died in Melbourne in 1975, when I was not quite eleven years old, I have the vividest memories of my maternal grandmother Helen Borthwick.

The cost of living luxuriously

In 1904, the Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna of Russia purchased as a gift for her sister, Queen Alexandra, a fan composed of two-color gold, guilloché enamel, mother-of-pearl, blond tortoiseshell, gold sequins, silk, cabochon rubies, and rose diamonds from the House of Fabergé in Saint Petersburg.

Embrace your inner nerd

The southern winter has arrived. For people in the northern hemisphere (the majority of humanity) the idea of snow and ice, freezing mist and fog in June, potentially continuing through to August and beyond, encapsulates the topsy-turvidom of our southern continent.

Humdinger

At a meeting by teleconference of the National Portrait Gallery Foundation last week, I found myself reporting that our forthcoming exhibition So Fine is going to be “a humdinger,” whereupon Tim Fairfax chuckled and said that he hadn’t heard that expression for years.

Poise and Carats

I keep going back to Cartier: The Exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia next door, and, within the exhibition, to Princess Marie Louise’s diamond, pearl and sapphire Indian tiara (1923), surely one of the most superb head ornaments ever conceived.

The National Portrait Gallery's 20th Anniversary

Last month we marked the twentieth anniversary of the formal establishment of the National Portrait Gallery, the tenth of the opening of our signature building, and the fifth of our having become a statutory authority under Commonwealth legislation.

The stately lotus

I spent much of my summer holiday at D’Omah, on the outskirts of Yogyakarta. Lotus and waterlilies sprout in extraordinary profusion in artful ponds amid palms and deep scarlet ginger flowers.

Indexing, the art of

The first index I created was for my first book, and, to my astonishment, that was almost twenty-five years ago.

Maria Caroline Brownrigg

At first glance, this small watercolour group portrait of her two sons and four daughters by Maria Caroline Brownrigg (d. 1880) may seem prosaic, even hesitant

The Rothschilds, the Montefiores, and the Victorian Gold Rush

Some years ago my colleague Andrea Wolk Rager and I spent several days in the darkened basement of a Rothschild Bank, inspecting every one of the nearly 700 autochromes created immediately before World War I by the youthful Lionel de Rothschild.

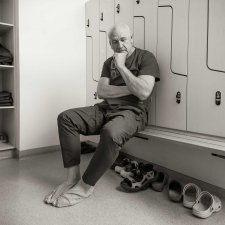

An active and contemplative life

From Cicero through St. Augustine and Coluccio Salutati right up to the present day, we have regularly weighed the significance, respective merits and competing priorities of the “active” versus the “contemplative” life. Can they coexist?

Queen Victoria

Last Sunday I had the privilege of appearing at the Canberra Writers’ Festival in conversation with Julia Baird. The subject of our session was Julia’s recent biography, Victoria the Queen: An Intimate Biography of the Woman who Ruled an Empire.