This is my last Trumbology before, in a little more than a week from now, I pass to my successor Karen Quinlan the precious baton of the Directorship of the National Portrait Gallery, after five supremely happy and rewarding years in the saddle (at the wheel, on the bridge?—take your pick). I have been looking back over the full run of 56 (with extras) and find to my astonishment that they cover the following more or less portraity topics, and a few that don’t really warrant a mention.

I started off with St Bernard of Clairvaux; the genera banksia and grevillea; Jane Austen’s Persuasion and Northanger Abbey in Sydney; the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary, and the late Dr Ursula Hoff. There were Dame Nellie Melba; one of James Gillray’s caricatures of Sir Joseph Banks (ours); the mixed pleasures of turning fifty, and statistics relating to the number of former prime ministers still living at any time since Federation. There was Anna Matveyevna Pavlova and the eponymous dessert, New Zealand’s premier cultural export. There were Josiah Wedgwood’s Sydney Cove Medallion; aspects of a childhood largely spent at Metung on the Gippsland Lakes; the selfie stick and the swizzle stick; the bellwether William Bligh in Australian history; the centenary of ANZAC; the mid-Victorian Sydney lyricist “Desda,” and the really terrible fruits of her, well, fruity collaborations with Maestro Ernesto Spagnoletti.

I examined the earliest ads in the Sydney Gazette. I dilated upon the only soldier at the Battle of Waterloo who was born at Port Jackson—Andrew Douglas White. There were Magna Carta; the ways in which Australian scientists and medicos punch above their weight in the world; Uluru and Kata Tjuta; The Queen; an ancient Major Mitchell cockatoo known as Cocky McGrath, and Cocky’s celebrated encounter with HRH The Duke of Edinburgh on the gravel drive at Government House, Melbourne.

Then came Thomas Woolner, the only member of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood who ever came to Australia; Louise Dyer of the Maison L’Oiseau Lyre; the late Robert Oatley AO; radiance, Moses, and Lord Kitchener of Khartoum. I then noted the centenary of the Easter Rising in Dublin, and the fact that in Regency Britain the quality of a portrait and the quality of the likeness were not necessarily the same thing at all. There followed Edward Lear’s “Inditchenous Beestes of New Olland”; Alfred Tennyson’s Enoch Arden; Pokémon Go (remember that?); an excursion into the obscure but delicious realm of dendrochronology; the late Mollie Murphy, and the Emperor Maximilian and Empress Carlota of Mexico.

This is to say nothing of Angkor Wat; His late Holiness Pope Shenouda III of Alexandria; my stalwart bear, the estimable Brownie, or Sir Stamford Raffles. And let us not forget The Chattri near Brighton in Sussex (effectively a sort of absorption of the Imperial narrative back into the South Downs, the heart of primitive England); photography (daguerrotypes); the arts of Latin America, specifically those seventeenth-century gun-toting angels in the Viceroyalty of Peru; dementia; the Conversation Piece; John Church Dempsey, and Charles Dickens’s Bleak House. Nor indeed Queen Victoria; the active and the contemplative life; The Rothschild Bank in New Court, St Swithin’s Lane; indexing (the art of); Central Java and the lotus; time and memory.

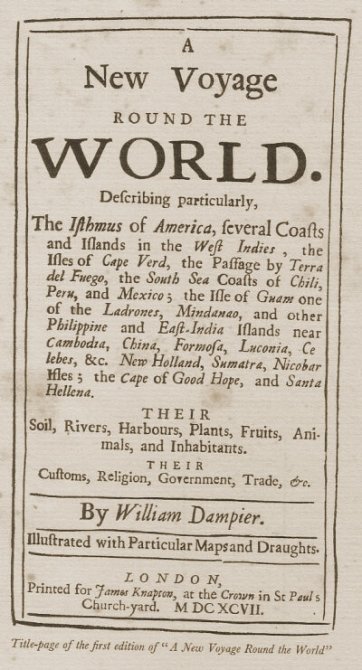

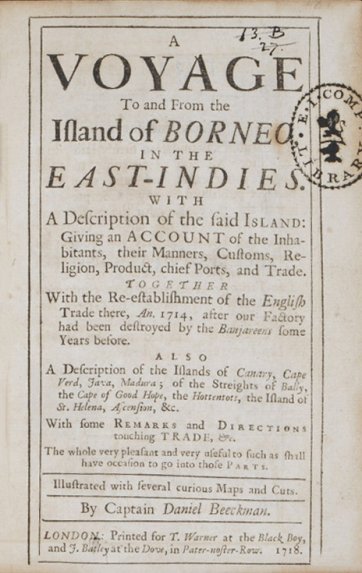

And let us not forget the House of Cartier; the platypus and Ovid in Hobart Town; the quest for equivalents in the present of costs and prices in history, or the Black Death. I see now that I lean towards the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but that should come as no surprise. They are the cultural territories where I feel more or less at home. Not too much should be made of any particular adjacency in this curious sequence. I was usually working to a hard monthly deadline, and casting about for an interesting subject—interesting above all to me, mindful of the fact that what you write cannot very well be interesting to other people unless it began by being interesting to you.

There are tributes and other topical matters, mostly arising from anniversaries. But what is so striking to me about the latter is that my tenure has extended slightly farther at either end that the full duration of World War I. Near the beginning, for example, I noted the fact that the fateful dominoes were sent clattering by the assassination in Sarajevo of the heir apparent to the Austro-Hungarian throne. We have just marked, less than three weeks ago, the centenary of the signing of the armistice on Marshal Ferdinand Foch’s railway carriage in the forest of Compiègne in Picardy at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918. Was ever a greater human catastrophe compacted into so brief a period, only slightly more than four years, 100 years ago? By strong contrast, it is now more than seventeen years since the destruction of the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan.

The rhythms of time, the patterns with which events unfold, do not necessarily accelerate in parallel with the daunting pace and colossal amount of digital communication with which we contend today. As I prepare to sign off, however, I feel that in the spirit of the approaching holiday season a festive cracker is in order, and in passing it into your hands, dear reader, may I thank you for accompanying me on this wonderful adventure. I wish you all a fond farewell.

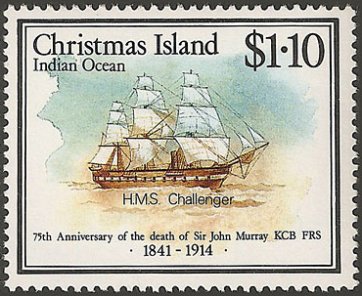

Christmas Island

10° 29’ 28.43” S, 105° 37’ 22.73” E

i migliori fabbri

To the staff of the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra

—past and present—

to whom I owe a profound debt of gratitude

for their generous support and hard work

over the past nearly five years,

which have been among the happiest

and most rewarding of my life,

this little bon-bon is humbly and respectfully dedicated.

A. T.

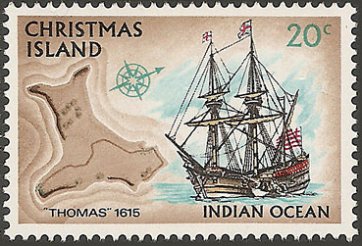

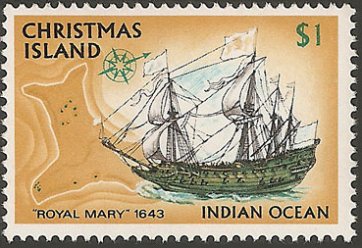

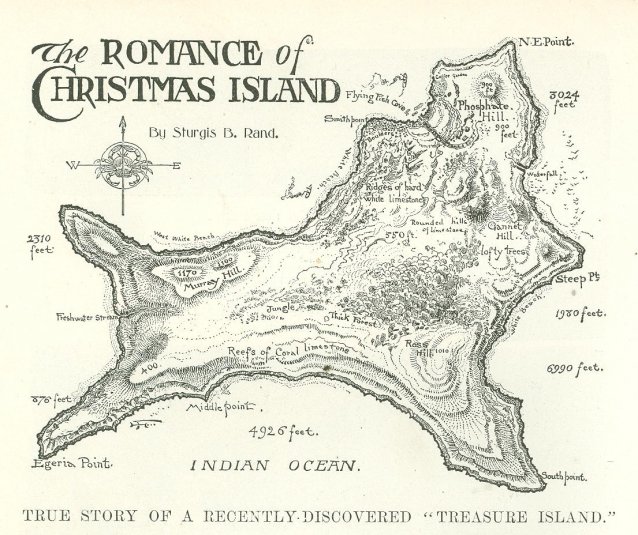

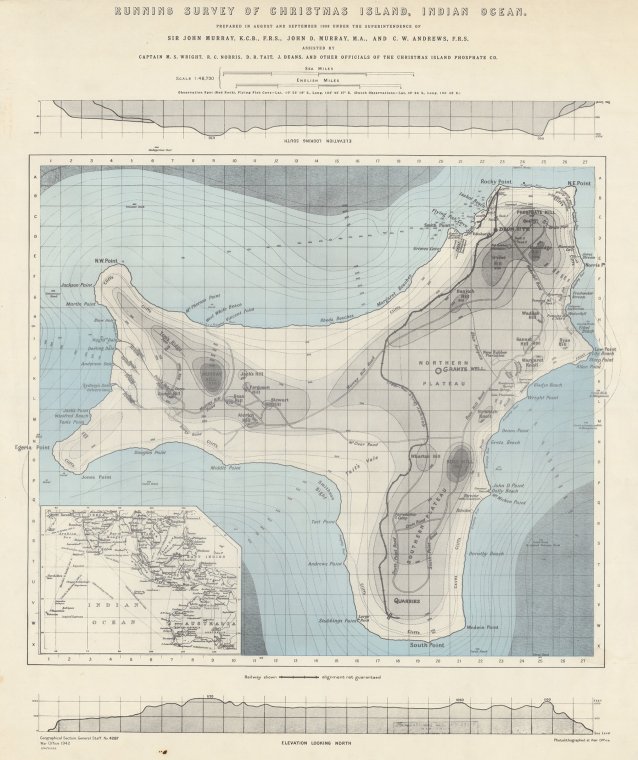

Canberra

Christmas Island is in the Indian Ocean, 364 kilometres (226 miles) south of Jakarta, Indonesia, 1,211 kilometres (815 miles) south of Singapore, and 2,621 kilometres (1,629 miles) northwest of Perth, Western Australia. It is 134 square kilometres (52 square miles) in area, and 70% of this is predominantly pristine tropical rainforest. Its coastline is approximately 72 kilometres (45 miles) long. The highest point above sea level is 361 metres (1,184 feet). The climate is tropical, with annual rainfall of approximately 2,000 millimetres (79 inches), most of which is concentrated into the November to May wet season. The island lays claim to an exclusive fishing zone of 200 nautical miles (370 kilometres). Much of this stretch of ocean is greater than three miles (2,640 fathoms, or 15,840 feet) deep. The present permanent population is approximately 2,070 (65% Chinese, 20% Malay, 10% European and 5% Indian and Eurasian).