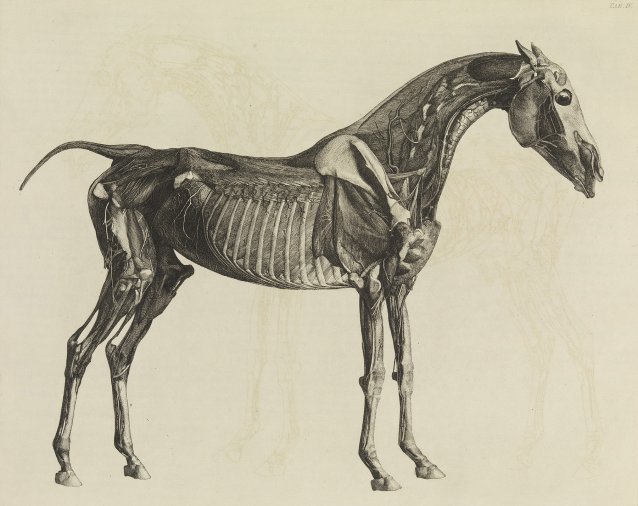

One of the chief aims of George Stubbs, 1724–1806, the late Judy Egerton’s great 1984–85 exhibition at the Tate Gallery was to provide an eloquent rebuttal to Josiah Wedgwood’s famous remark of 1780: “Nobody suspects Mr Stubs [sic] of painting anything but horses & lions, or dogs & tigers.” Yet in his lifetime, the horse was of course as much a problem for Stubbs’s reputation as it was the cornerstone of his artistic practice. He did much to make it so. Though Stubbs was the Vesalius of the horse, and painted some of the greatest equine portraits that exist, within the institutional framework of the London art world he was stuck with the label of “horse painter,” and tried in vain to shed it. His work as an anatomist was at times a problem too, though it brought him into contact with the Hunters, William and John. It was probably Stubbs’s work on midwifery in York around 1751 that caused Sir Thomas Frankland to describe Stubbs in a letter to Sir Joseph Banks as a portrait painter in York “formerly of vile renown.”

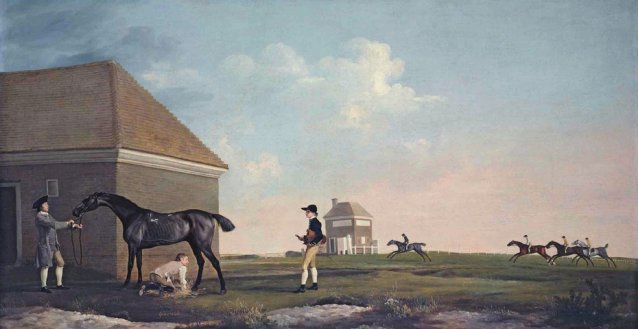

Yet to some degree Stubbs’s artistic reputation still remains comfortably mounted on horseback. Stubbs and the Horse, which was curated by Malcolm Warner, the then senior curator of the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, was smaller, tighter and more sharply focused than Egerton’s panoramic Tate show. It consisted of thirty-five paintings, including twelve portraits of single horses, of which a number are unrivalled masterpieces, such as Lustre, With a Groom, c. 1760–62 (Yale Center for British Art). There were five fine group portraits, including The Duchess of Richmond and Lady Louisa Lennox Watching the Duke of Richmond’s Racehorses at Exercise, 1759–60 (Goodwood), and Sir Peniston and Lady Lamb, with Lady Lamb’s Father, Sir Ralph Milbanke, and her Brother John Milbanke, 1769–70 (National Gallery).