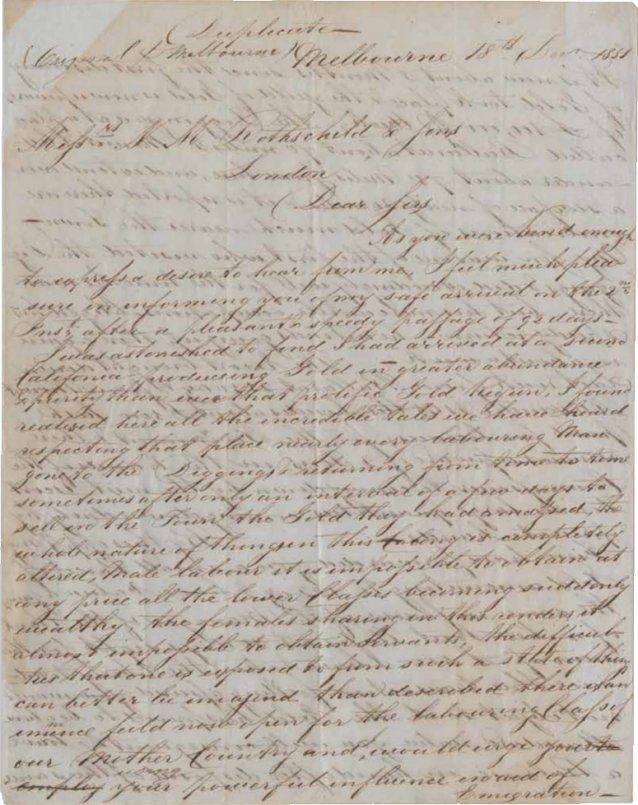

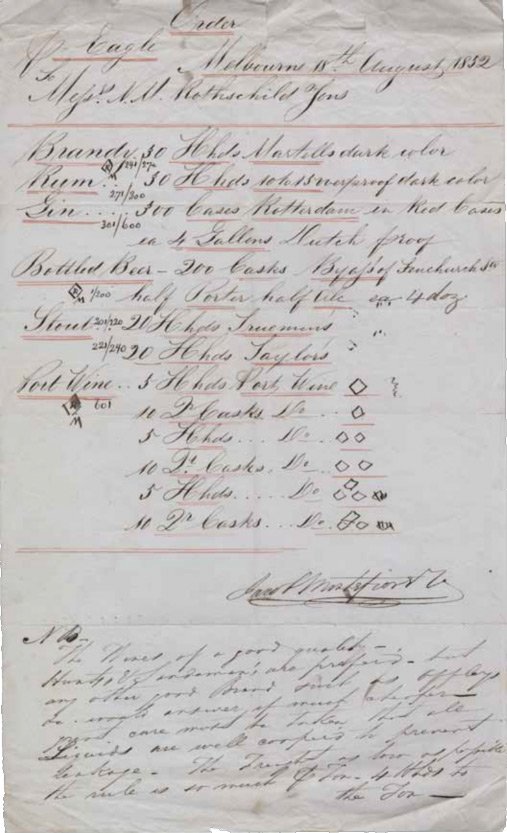

Upon most if not all of these vital necessities the diggers depended, and there were many such shipments. While Rothschilds could supply these goods at favourable London prices, and take advantage of the margin afforded by the dizzying rate of inflation in Victoria, the Montefiores were hit hard by the excessively high costs of doing business there. They were also hit hard by the accumulating cost of borrowing more and more from London in order to convey the goods from Melbourne to the diggings, and to cover a multitude of exorbitant overheads.

Montefiore may have been careful to maintain strict confidentiality in his dealings with New Court, but other merchants in Melbourne certainly caught wind of their relationship. In an unsolicited démarche on 1 January 1852, for example, Reuben (or Rheuben) Barnett consigned three boxes of “gold dust” directly to “Baron Rothschild,” effectively by-passing the Montefiores. Perhaps cheerfully inspired by some New Year’s resolution, Barnett was a lessee of ships on the Bass Strait (Van Diemen’s Land) run and, for the time being, also innkeeper of the Exchange Hotel in Collins Street, Melbourne. In his covering note, Barnett sought from them the safest form of remittance, but also boldly raised the possibility of representing Rothschilds in Melbourne into a glorious future, full of potential. The mark on Barnett’s boxes—the letter “B” inside a magen david—together with his signature in fairly hesitant Hebrew, made an obvious claim upon the Rothschilds’ attention. This he reiterated a little later in a separate follow-up letter, explicitly claiming in a postscript that he was once well known to Nathan MAyer Rothschild himself—a claim that was presumably impossible either to disprove or to verify. It is not clear whether this Rheuben or Reuben Barnett is the same “Polish Jew” a watchmaker, who was convicted in 1843 in the Central Criminal Court of receiving £100 of India silks and sentenced to seven years’ hard labour and afterwards transported to Van Diemen’s Land. It is possible. We know very little else about Barnett’s Melbourne business, except that he brought criminal charges against the master of his vessel the Jenny Lind (Argus, Saturday, March 26, 1853), but not long afterwards appeared several times in the Insolvent Court in Melbourne in 1853 and again in 1856 (Argus, Tuesday, July 5, 1853, and Thursday, June 26, 1856).[10]

Evidently, for the time being the Rothschilds preferred to deal with the Montefiores instead—and they were wise to do so—but their confidence in their Melbourne cousins was not limitless. To obtain an independent assessment of the progress of their investments in Victoria, the bank despatched from California to Melbourne a trusted employee, the peripatetic clerk John Luck. His brief was discreetly to monitor the Montefiores’ transactions—even to the point of furnishing unofficial audits—while, at the same time, scouting independently for new business opportunities, and also trading on his own account, using a line of credit naturally furnished by the bank on the basis of equal caution. These practices were identical in California, South America, and many other places where the bank sustained relatively informal agency arrangements, so the Montefiores were not at all unusual in being watched closely. In the end, they became hopelessly over-extended, and in 1855 faced bankruptcy, defaulting on substantial advances from the London branch. The Rothschilds’ agent Jeffrey Cullen sailed out to Melbourne to act as fireman.[11]

What is now clear is that the decision of the firm of N. M. Rothschild & Sons in 1852 to secure the lease on the Royal Mint Refinery in London must have been driven at least in part by the immense flow of gold from Victoria. The Paris branch had in any case refined bullion since 1827, when James de Rothschild opened his smelter in the quai de Valmy. Indeed Michel Benoît Poisat, James’s business partner in that venture, eventually oversaw the technical aspects, equipment and staffing of the London refinery.[12] In 1835, the bank drew up a contract with the Kingdom of Spain to market the output of the Almadén mercury mines, thereby securing a vital ingredient in the gold-refining process. And it is no accident that many of the Montefiores’ reports from Melbourne were translated and sent to Paris, presumably to assess the viability of extending to London the firm’s production of gold bullion. And in the broadest sense, what this capsule of Australian correspondence so deftly illustrates is the capacity of the bank to think and act globally, on a dizzying scale as well as on the almost microscopic, the better to reinforce, support and nourish a growing network of mutually sustaining, and enormously profitable interests. In the ten years from 1851 to 1861 most of the 25.2 million ounces (787 tons) of gold extracted by hand from the creek beds, escarpments, gravel pits and stony hills of central Victoria passed through the hands of N. M. Rothschild & Sons in London. This was worth far more to the firm than every one of those shipments of hogsheads of middling-quality Sandamans pale sherry, pickles, Barcelona nuts, raisins, and currants, and even the losses incurred by their well-meaning and by no means incompetent Melbourne cousins by marriage.

Footnotes

[1] I am most grateful to Melanie Aspey and all the staff of the Rothschild Archive in London for their warm hospitality and generous assistance in preparing this article.

[2] The best concise histories of the gold rush in Victoria are still Geoffrey Serle, Golden Age: A History of the Colony of Victoria, 1851–1861, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1963, and Geoffrey Blainey, The Rush That Never Ended: A History of Australian Mining, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1963. To these may now be added Bruce Moore, Gold! Gold! Gold! A Dictionary of the Nineteenth-Century Australian Gold Rushes, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2000, and a host of more specialist books and articles.

[3] Mary Howitt Walker, Come Wind, Come Weather: A Biography of Alfred Howitt, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1971, p. 37.

[4] Rothschild Archive, London, XI/38/7/6.

[5] Except by Niall Ferguson, The World’s Banker: The History of the House of Rothschild, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1998, pp. 578–80. For the Montefiore brothers, see Israel Getzler, “Montefiore, Joseph Barrow,” in Douglas Pike, ed., Australian Dictionary of Biography, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, vol. 2, 1967, pp. 250–51; Martha Rutledge, “Montefiore, Jacob Levi,” in Douglas Pike, ed., Australian Dictionary of Biography, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, vol. 5, 1974, pp. 270–71; George F. J. Bergman, “Montefiore, Eliezer Levi,” in Douglas Pike, ed., Australian Dictionary of Biography, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, vol. 5, 1974, p. 269.

[6] RA XI/38/7/1.

[7] Amy Woolner, Thomas Woolner, R.A., Sculptor and Poet: His Life in Letters, London: Chapman and Hall, 1917, and New York: E. P. Dutton, 1917, repr. New York: AMS Press, 1971. My new edition of Thomas Woolner’s goldfields journal with introduction and scholarly apparatus awaits publication.

[8] In Exodus 22:21 and Deuteronomy 10:19 we find, "love ye therefore the stranger: for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt" (KJV). Nevertheless it seems far more likely that Montefiore used the term here to describe gentiles (the vast majority). I am grateful to Rabbi John S. Levi for his assistance on this point.

[9] RA XI/38/7/5.

[10] See “Barnett, Reuben (Rheuben),” in John S. Levi, These Are the Names: Jewish Lives in Australia, 1788–1850, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press (The Miegunyah Press), 2006, pp. 68–69.

[11] Ferguson, p. 578.

[12] Michele Blagg, “The Royal Mint Refinery, 1852–1968,” The Rothschild Archive, Review of the Year: April 2008 to March 2009, London: The Rothschild Archive, 2009, pp. 48–49.