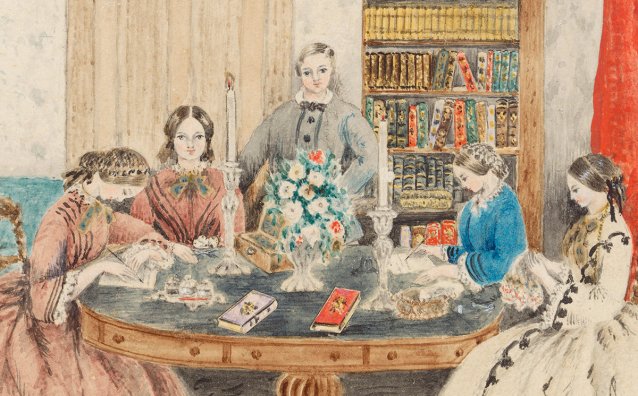

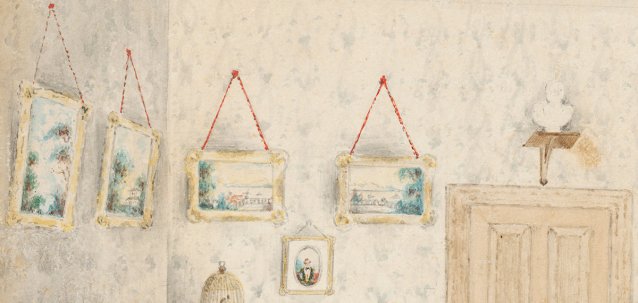

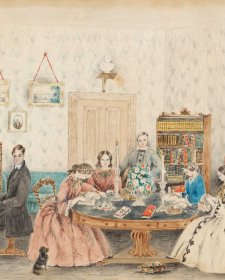

At first glance, this small watercolour group portrait of her two sons and four daughters by Maria Caroline Brownrigg (d. 1880) may seem prosaic, even hesitant. Yes, it is the only known work by a relatively able amateur with no more training than was conventionally meted out to young British ladies in what passed for a genteel, certainly gender-specific late-Regency education. However, securely fixed to the drawing-room of “Yarra Cottage,” Carrington, on the north shore of Port Stephens in the Hunter Region of New South Wales in 1857, this picture stands at the intersection of a number of grand colonial, indeed imperial narratives.

In 1971, the late Linda Nochlin published one of the most influential art-historical essays of our time. Its title “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” was not a rhetorical question. Rather, it was originally put to Linda Nochlin by the art dealer Richard Feigen, and it steered her towards a distinguished career of feminism in art history. Her essay was an attempt both to answer the question and to dismantle its premiss. The present painting, a remarkable survival, would have strengthened her case on both grounds.

As with so many of their peers, the Brownriggs’ path through the British Empire was peripatetic. Maria Caroline was the daughter of a Captain Matthew Blake who by 1829 was stationed with his family at the Cape of Good Hope. There, on 19 January of the following year, she married Lieutenant Marcus Freeman Brownrigg, R.N. (?1800–1884), the second son of Major-General Thomas Brownrigg of Medop Hall, Gorey, Co. Wexford. General Brownrigg’s more famous brother General Sir Robert Brownrigg, Bart., G.C.B., was for a time Military Secretary to the Duke of York and subsequently third British Governor of Ceylon under the old Honourable East India Company dispensation. Born in Dublin, Marcus Brownrigg was a typical product of the middling ranks of the Anglo-Irish ascendancy for whose relatively impecunious younger sons the Royal Navy, the Church of Ireland, Trinity College and the law provided conventional berths, normally secured by patronage.

Maria Brownrigg is scarcely knowable by any means other than the present painting—wherein lies much of its value—and through the career of her husband. No letters from or to Maria have yet been identified in the archives; she is barely a shadow at her husband’s side, which is, alas, not unusual for many mid-Victorian colonial women. However, even by nineteenth-century HEIC and Colonial Office standards, the Brownriggs’ life-long itinerary was impressive.

The Brownriggs spent the first two years of their married life in Cape Town, before Marcus, a first lieutenant aboard H.M.S. Sparrowhawk, was posted to the Nore Station. This may have been the first time the Brownriggs ever set foot in England, but their sojourn, probably in Kent, did not last for long. In 1834, Marcus went on half pay, was promoted Captain, and only once re-entered active service in later years. Their first child, Marcus Blake Brownrigg (the young man seated here at the piano) was born in London in 1835, and shortly afterwards Brownrigg was appointed confidential agent at Mauritius for Messrs. Cockerell & Co., a predominantly East India trading firm in the City of London. They duly sailed to Port Louis where Marcus Senior’s sister, Martha Henrietta Danford (d. 1845), already lived with her husband and family. Soon afterwards, the Brownriggs continued on to Bombay. It seems likely that, although he had died in 1833, the lingering influence in East India Company circles of Marcus’s powerful uncle, Sir Robert Brownrigg, drew them there. Certainly, in 1836 Brownrigg set up a new “house of agency” for Cockerells in Bombay. He soon became Chairman of the local Chamber of Commerce and a Director of the Government Bank. This turned out to be the apex of his mercantile career.

In the meantime, by 1839 Maria had produced three daughters—Emma Blake, Annie Henrietta and Katie; she must have been more or less constantly pregnant; the children arrived at more or less ten-monthly intervals. She (and they) were fortunate to survive the depressing prevalence of memsahib and Anglo-Indian infant deaths from dysentery, or worse. A second son, Crosbie Blake, soon followed, as well as a fourth daughter Carrie. In 1843, the Brownriggs left Bombay and sailed to Liverpool where Marcus established a new branch of Cockerells. Whether this was a case of over-reach, or else the new enterprise fell foul of the free-trade crisis during and after the Irish Potato Famine (which also affected Scotland), the Liverpool business soon failed, and by 1847 the firm’s local creditors managed to recoup only about seven to ten shillings in the pound.

Intriguingly, at this low point Brownrigg accepted a fresh commission in the Royal Navy. He may have had no choice, and it seems likely that patronage played a part in steering him toward the opportunity. This time, Brownrigg was stationed in Plymouth until 1851, when he was gazetted Commander. Soon afterwards, he was in Glasgow with the Colonial Land and Immigration Commissioners, which post appears to have prompted him to apply for the General Superintendency of the Australian Agricultural Company’s million-acre pastoral and coal operations at Port Stephens and Newcastle, New South Wales. He gave his age as 50. It certainly helped that a cousin of his, J. S. Brownrigg Esq., M.P., was the Company’s Chairman of Governors, and also sometime Chairman of the Bank of Australasia.

In November 1852, the Brownriggs (accompanied by two servants) arrived in Sydney via Melbourne aboard a vessel that had brought them all the way from London. There they joined Marcus’s brother William Meadows Brownrigg, a surveyor, but stayed initially at Government House as guests of the Governor, Sir Charles Augustus FitzRoy. Soon afterwards the family was en poste at Port Stephens. It is worth noting that this was the third colonial outpost to which Brownrigg proceeded in which members of his own family were already embedded.

Not knowing much about cattle, or indeed the extraction of coal, Commander Brownrigg was obviously ill-suited to his position. In 1856 he was dismissed for incompetence, and was also sued—an early, but by no means the first, instance of colonial private enterprise demanding a somewhat higher degree of ability than was exacted or indeed expected by successive colonial secretaries in Sydney. On the other hand, his dismissal was so regretted at Newcastle, in particular, that a public meeting of gentlemen was organized and a friendly address to Brownrigg was adopted by acclamation. Others followed, as well as a lively, probably embarrassing, correspondence in the Sydney and Hunter press hotly defending Commander Brownrigg’s management of cattle, in particular, and deploring the loss of a gentleman at Port Stephens whose family had set such a conspicuous example of Christian piety. True, such effusions may have been merely conventional, but this last observation certainly redounded to the credit of Maria Caroline Brownrigg.

When Maria executed this group portrait in 1857, Commander Brownrigg was absent in Sydney attempting to clear his name, and the family had moved to “Yarra Cottage,” Carrington, on the north shore of Port Stephens, a discreet distance from the household of his newly-appointed successor. Rather like Elizabeth Macarthur and many other colonial ladies who preceded her, in her husband’s absence Maria was effectively placed in charge of household, servants, convicts, children, horses and livestock. Commander Brownrigg was evidently more or less successful because by 1859 the family had moved to “Glencoe,” Rollands Plains, on the Wilson River near Port Macquarie, and Brownrigg was police magistrate, secure in a relatively undemanding office under the crown. There, their second daughter, Annie Henrietta, married William Cowper, son and namesake of the Australian Agricultural Company’s former chaplain, with whom they had obviously worshipped and socialised at Port Stephens.