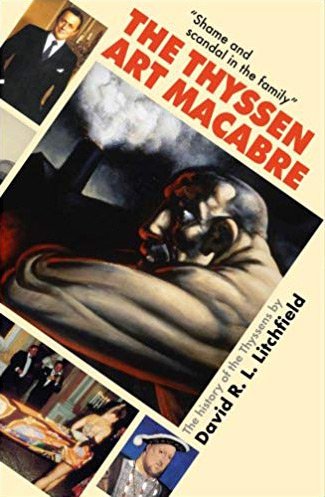

Books seldom make me angry but this one did. At first, I was powerfully struck by the uncanny parallels that existed between the Mellons of Pittsburgh and the Thyssens of the Ruhr through the same period, essentially the last quarter of the nineteenth century. But that is where the resemblance ends. Upon re-reading this piece just now, which was first published in The Times Literary Supplement (with a few irritating edits that I take the liberty, here, of reversing), I’m really struck by a strength of tone, notes even of indignation, that feel most unfamiliar to me. I’m a pretty equable sort of bloke. Nevertheless, the sharp tone of this piece was genuine and I’m proud of it.

The Thyssen Art Macabre

David R. L. Litchfield

in collaboration with Caroline Schmitz

Quartet Books, 2006

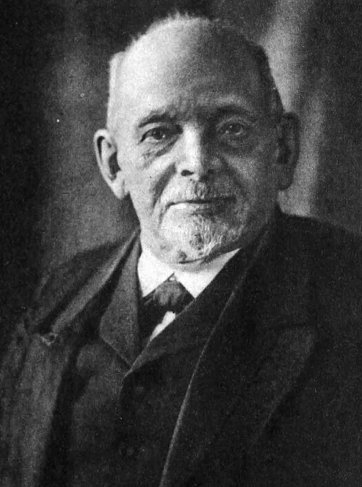

Beginning in the third quarter of the nineteenth century, in a province about to be transformed by heavy industry, with shrewd talent for business and sheer hard work, the sons of the sober proprietor of a minor local bank devote their life to building a huge industrial conglomerate. Buoyed by an unlimited international demand for coal and steel, and by the absence up to a certain point of income, company or wealth tax or planning regulations of any kind or effectively unionized labour; supported by equally ambitious joint-venturers; barely interrupted by the slump of the 1890s—and not even particularly incommoded by the First World War, on the contrary: it was great for the banking and steel branches of the family business—the mesh of intertwining companies they create generates profit on a scale hitherto unknown, such that the shareholders’ vast wealth is almost impossible to calculate. Their banking, steel, coal, gas, oil and transport interests continually refinance and stoke one another, bringing about unstoppable expansion, causing the whole region to become one of the industrial power-houses of the continent.

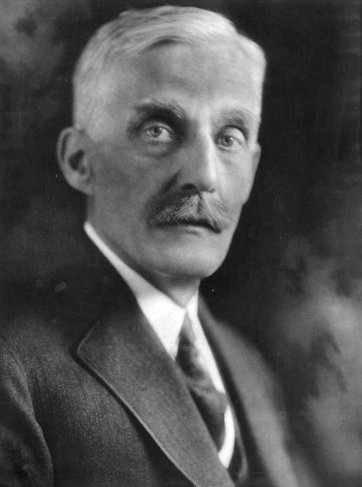

One brother, short, thin-voiced, frugal in his personal life, emerges early as the dominant personality; his knowledge of and hold over the concern is total. His marriage collapses, at a time when divorce was wholly scandalous. In old age, he becomes interested in art. Dutch paintings hang in the small, but comfortable apartment they keep in the nation’s capital; a large but cold principal residence remains within walking distance of the office, not far from belching factories. His handsome, well-educated son and heir inherits his interest in fine art, but disappoints the father by not inheriting his single-minded passion for business above all else. After the old man dies, universally regarded as one of the greatest industrialists of the age, the son’s art collecting activities accelerate and become exceedingly ambitious. He also is finally able to indulge his passion for bloodstock, partly freed from his remote, self-disciplined father’s disapproval.