The peripatetic career of Ambrose Patterson (1877–1967), Ramsay’s fellow student at the National Gallery School, would lead him to an eventual position as Professor of Art at the University of Washington, Seattle. In Paris for his second round of study, Patterson was sponsored by the renowned soprano Dame Nellie Melba (1861–1931), whose sister Isabella (1866–1950) was married to Patterson’s brother Thomas. Ramsay’s studio was near that of Patterson’s, who shared his with the American Impressionist painter Frederick Carl Frieseke (1874–1939). Working in such proximity, the artists shared compositional ideas, and sometimes used each other as subjects.

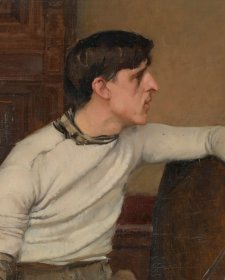

One of two full-length works Ramsay produced of his friend, Portrait of Ambrose Patterson (1901–02) depicts its subject sitting sideways on a chair, arm draped over its back, brushes clutched in his hand. Patterson’s twisting posture, which emphasises his long neck and strong features, was less prominent in the original context. Ramsay gifted the work to Patterson, who later stored it in Belgium where it was subsequently damaged. Years later, Patterson cut the canvas down to the current, much tighter iteration that makes the composition seem out of proportion. Ramsay’s standing within this close group of expatriates was confirmed when he made a spectacular début at the New Salon of March 1902, with four paintings accepted. In a further distinction, usually reserved for members or associates of the Société des Artistes Français, Ramsay’s paintings were all hung ‘on the line’ (at eye level).

In gratitude for Ramsay’s advice and guidance about his own work, Patterson arranged an introduction to Melba, who agreed to sit for Ramsay. Portrait sketch of Nellie Melba (1902) was produced in Ramsay’s studio in March, and the artist would comment of his sitter, ‘She was intensely sympathetic, and I quite fell in love with her ... She actually sat for half an hour for me, to do a sketch, but I was a bit flabbergasted and too nervous to do a chef d’œuvre [masterpiece].’ Impressed with Ramsay’s diligence and growing reputation, the prima donna invited him to paint her in London, with all the social cachet that implied. The small study Sketch of Nellie Melba (1902), painted in the drawing room of her Great Cumberland Place mansion, is all that remains of this brief, halcyon period when Ramsay was on the cusp of realising his aspirations.

Staying with Sir John Longstaff, Ramsay was making the most of his time in London. He had four paintings accepted for the British Colonial Art Exhibition, but then became acutely ill. Diagnosed with the incipient tuberculosis that would eventually kill him, Ramsay’s doctors felt that a combination of two harsh winters in Paris, poor nutrition and overwork had damaged his health. Melba advanced Ramsay the funds for his immediate return to Melbourne, which was thought to be a better climate for recovery. Writing to his Scottish cousin John Lennie in June 1902, Ramsay’s despondency about his enforced retreat was palpable: ‘Just when I have absolute success within my grasp, just when I see the probabilities of my being a successful painter, that it should all be snatched from my grasp’.