Twin chics

by Joanna Gilmour, 6 July 2021

The experience of seeing artworks in the flesh was one of the many pleasures we had to relinquish for a while during 2020. Galleries and museums were locked down and exhibitions were virtual. We became more acquainted with methods of accessing art from a distance and had to content ourselves with reproductions of paintings in books or online. Hardly ideal when you’re devising an exhibition, especially one like Australian Love Stories – an exhibition that seeks to negate the notion that portraits are little more than faithful or dispassionate transcriptions of an individual’s outward appearance. So, having been in thrall for the past several months to reproductions of Carla Fletcher’s luminous portraits of fashion designers Jenny Kee and Linda Jackson, to finally be able to linger over the real things has been something of a revelation, a timely object lesson in the truism that one should never take things at face value. Splendid evocations of the style and spirit of their subjects and multilayered in both the figurative and literal sense, they are affirmations as well that the best portraits are those which are deeply and inextricably infused with feeling.

‘My connection with both Jenny Kee and Linda Jackson has been deeply pivotal as an artist and a human being in general’, Fletcher said in 2016, when her portrait of Jackson saw her shortlisted for the Archibald Prize for a third consecutive year. Fletcher calls the work the ‘twin soul’ of her portrait of Kee, a 2015 Archibald finalist and the portrait which initiated a vivid shift in the artist’s practice. Though Melbourne-born Fletcher has featured regularly in prestigious portraiture competitions since graduating with distinction from RMIT – the Lester Prize, the Shirley Hannan National Portrait Award and the Portia Geach Memorial Award, as well as the Archibald – her portraits of Kee and Jackson represent a mesmeric departure from the large-scale, exquisitely rendered drawings that had been her prize finalists previously. For her first tilt at the Archibald, in 2010, Fletcher created a two-metre wide drawing of blues musician C W Stoneking, primarily in pencil and pen on a layer of white acrylic paint, using a single colour – red – for his bowtie only. Her portrait of actor Joel Edgerton, executed in pencil and acrylic and a finalist in the Lester Prize (formerly the Black Swan) in 2011, likewise involved minimal colour, rendering Fletcher’s consummate draughtsmanship all the more striking. Speaking about her portrait of Stoneking in 2010, Fletcher explained that as an artist she has always being interested in ‘the fundamentals’, specifically drawing, and that she complemented her formal study of the discipline at art school with sessions alongside a Melbourne plastic surgeon so that she might deepen her understanding of anatomy. ‘I studied like the Old Masters but in a contemporary context’, Fletcher says.

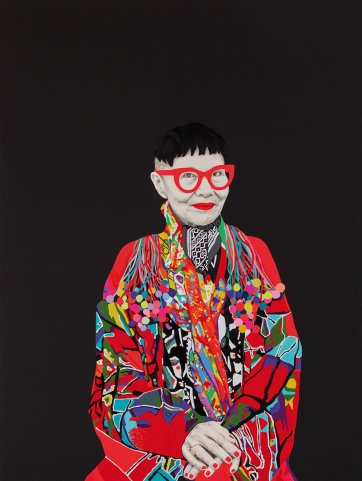

Like the portraits of Stoneking and Edgerton, the images of Jenny Kee and Linda Jackson demonstrate Fletcher’s remarkable skill in drawing, with the sitters’ faces and hands precisely, tightly delineated in pencil and graphite and then punctuated with intense shards of colour: Kee’s radiant red fingernails; Jackson’s glacially blue eyes and the glittering opal on her right ring finger; their incandescent lips and glasses. But all restraint – and similarity with earlier works – ends there, as their figures erupt out of inky backgrounds in glorious textures and colours, as if in tribute to the effect of the pair’s creative partnership on the largely derivative Australian fashion scene of the 1970s. They first met at a gallery in Paddington in 1973. Jackson had studied fashion design and photography in her native Melbourne before travelling to New Guinea, Asia and Europe and absorbing the techniques found in everything from traditional textiles to haute couture. Kee, who grew up in Bondi, was 26 and had returned home after spending much of the 1960s in London, working in vintage fashion at the Chelsea Antique Market. Soon after getting back to Sydney, Kee recollects, ‘I was told I had to meet an extraordinary Melbourne woman called Linda’. Jackson remembers likewise: ‘People kept saying to me, “You have to meet Jenny” … And they were right; when I first met her I just thought, “That’s Jenny, that’s her.” It was like I’d been waiting for her.’

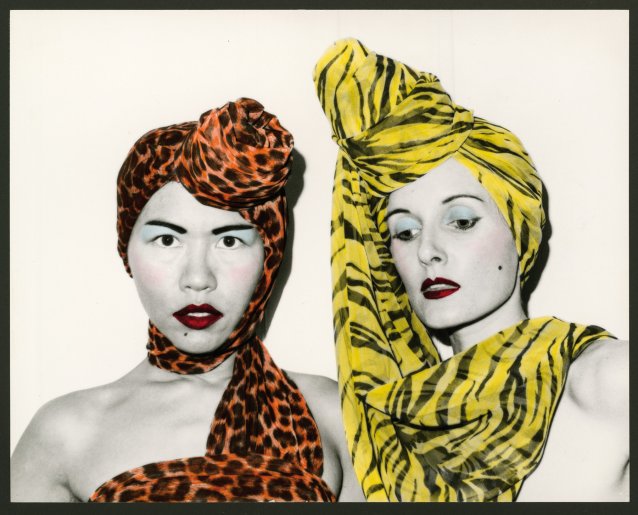

‘We felt connected immediately’, Kee says. ‘Ours was a creative version of a first love, a union so passionate it was almost like an affair.’ In addition to a shared passion for vintage styles and reverence for the artistry and skill inherent in the bespoke and the handmade, Jackson and Kee connected through a deep love of nature. ‘She became my muse’, says Jackson. ‘We spent a lot of time in the Australian bush together ... she would dress up and be the focus of my early photography.’ Kee recollects these occasions as ‘really divine meditative experiences, it wasn’t like big fashion shoots; it was just Linda and me, wandering in the beautiful nature that we loved’ – and then conceiving ways of translating their discoveries into wearable art.

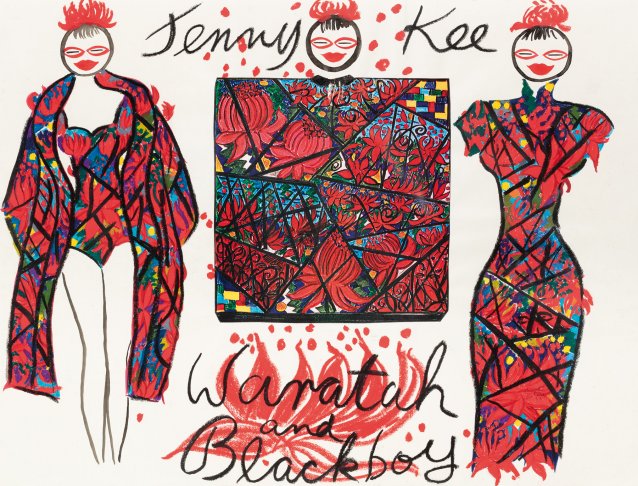

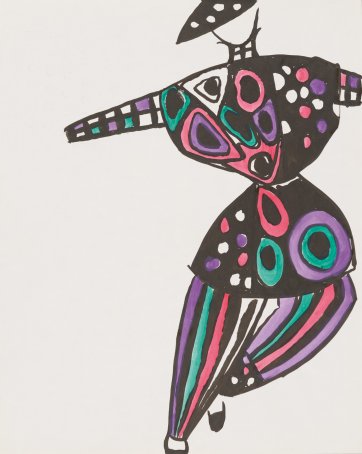

Just as significantly, their profoundly collaborative and bountiful friendship started amidst the optimism of Australia in the Whitlam years – and thus in a cultural climate that was apt to embrace their exuberant sartorial celebrations of beach, bush, desert and reef. From the outset, Jackson’s and Kee’s creations were distinct in their blithe, bold use of Australian motifs and iconography: a blue linen suit appliqued with the sails of the Sydney Opera House, for instance; a silk chiffon slip decorated with hand-painted images of tropical fish; the Scribbly Gum tunic shedding strips of silk bark; or the chunky, handknitted dresses and jumpers adorned with rosellas, koalas, waratahs and sprigs of wattle. ‘Talk about “It’s time”. It was time for those clothes’, Kee says. ‘We were free to do what we wanted. We didn’t want to be European, we wanted to be ourselves’, Jackson said in 2019. ‘And we were doing something more outrageous here than they were doing anyway.’ Or, as Kee has recalled of her original ideas for Flamingo Park, the boutique they opened in Sydney’s Strand Arcade in 1973: ‘I wanted it to be like nothing else on the planet’.

It’s entirely apposite, then, for Fletcher to have created portraits of the duo that, side by side, form a modern-day altarpiece, a pair of works which seem to radiate a mystic presence while joyfully documenting the powerful terrestrial sources of their subjects’ inspiration. Reflecting the delicacy, texture, tactility and craftsmanship that distinguishes Jackson’s and Kee’s creations, Fletcher utilised collage to form the sitters’ figures, dress and accessories, layering pieces of archival, glossy and self-adhesive papers to clothe them in the glowing colours, patterns and shapes of their own works. The technique, in fact, mirrors the designers’ own creative methods: their intuitive, reflective sketching; the process of assemblage and layering of fabrics and imagery intrinsic to the tailoring of individual pieces. Or, as Kee has explained of her Black opal and White opal fabrics – chosen by Karl Lagerfeld for a collection he created for Chanel in 1983: ‘Karl was entranced by the way I collaged my clothes with patterns and prints’.

Jackson, who has described her first visit to the opal-mining towns of Lightning Ridge and Yowah as one of the turning points in her career, is depicted wearing an opal neckpiece she designed in collaboration with Adrian Lewis Jewellery and Berta Opals. Her sleeves and headscarf are fashioned from a fabric in molten pink, orange and purple tones; and her shimmering, doublet-like garment is overlaid with a delicate shawl formed from multiple Sturt’s Desert Pea shapes. Kee is cloaked predominantly in a vibrant red – the colour of her beloved waratah – punctuated throughout with contrasts, including patches of charcoal black and shoots of green to suggest both the bushfires which have imperilled Kee’s Upper Blue Mountains home and the regeneration that has followed them. Fletcher travelled there for a weekend sitting, joining Kee on the precipitous descent into the Grose Valley at Blackheath and collecting ochre she later ground down and incorporated into the background of the portrait. ‘She asked me what version of her I wanted’, Fletcher remembers, ‘and when I thought about what I wanted from the work ... I wanted to get the highest frequency possible for her energy, and I think that involved the colour, and she just got it.’ Indeed, Kee has described the waratah as her totem, ‘the brazen red goddess of the bush’. ‘I am always astonished that such beauty can spring from such devastation. I see waratahs as the essence of fire – from the destruction comes rebirth. From personal tragedy, I have been reborn through representing the waratah in my art.’

By invoking the transformation and transcendence inherent in collage, Fletcher has created portraits in which the key elements – sitters, artist, story and medium – are perfectly integrated; and which, in their colour and iconography, synthesise an iconic and enduring friendship with the spirituality, joy and prescient environmental sensibilities which are at the core of the duo’s creative work. Though made for the Archibald Prize, these are vastly more than just ‘portraits painted from life, with the subject known to the artist’ – as blandly stipulated in the Prize’s terms and conditions. In complete contrast, they are examples of portraits in which the sense of connection between artist and subject is palpable, and which give credit to the notion that portraits can somehow capture the presence, individuality and essence of those we love and connect to most.

Related information

Australian Love stories

Family, friends, fanatics and foes (and everything in between!)

Previous exhibition, 2021Reconnect and reflect with our new major exhibition, Australian Love Stories (in real life!) as we explore love, affection and connection in all its guises.

Portrait 65, Autumn/Winter 2021

Magazine

Hugh Ramsay, the fashion of Jenny Kee and Linda Jackson, Peter Wegner's centenarian series, John and Elizabeth Gould's family connections, Karen Quinlan's top five portraits and more.

Splendid, many-splendoured

Magazine article by Sandra Bruce

Sandra Bruce gazes on love and the portrait through Australian Love Stories’ multi-faceted prism.