The catechist and the cricketer

by Stephen Valambras Graham, 6 July 2021

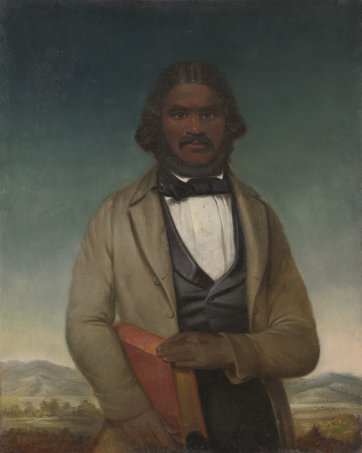

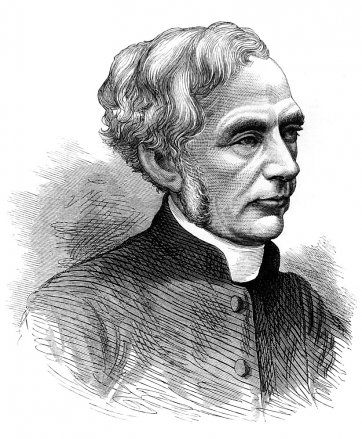

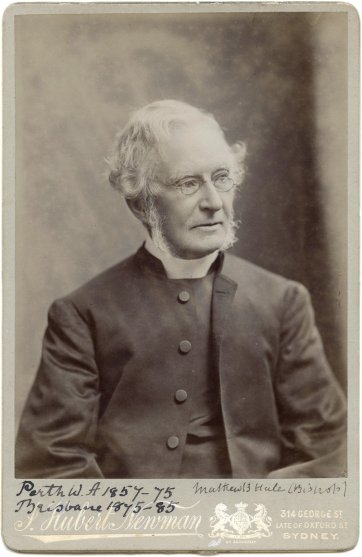

Mathew Blagden Hale, Archdeacon of Adelaide, established the Poonindie Training Institution for Aborigines near Port Lincoln towards the end of 1850, a social experiment forcefully recounted in Peggy Brock and Doreen Kartinyeri’s Poonindie, the Rise and Destruction of an Aboriginal Agricultural Community. During his tenure at Poonindie, Hale commissioned portraits of two pupils, Samuel Kandwillan and John Nannultera, from John Michael Crossland, an artist making a name for himself in the young colony as a society portraitist. Kandwillan came to his studio during a trip to Adelaide in February 1854 when he participated in a game of cricket at St Peter’s College. Nannultera visited the artist in October of that year while staying with the Elder family in Adelaide. These two iconic works, mapping the contours of colonial integration (super)imposed upon Aboriginal identity, have been on display together as part of the 2020-21 rehang of nineteenth-century Australian art at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA), Belonging: Stories of Australian Art.

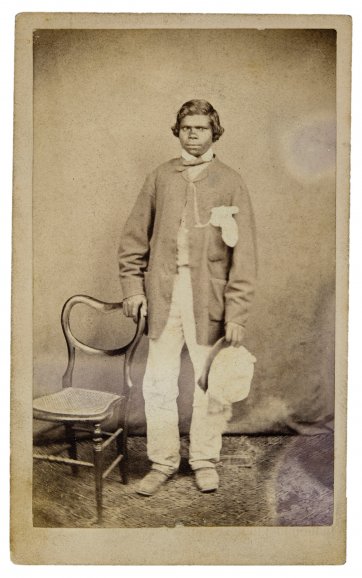

Costume and clothing as material forms of historical evidence, argues art historian Marcia Pointon in Portrayal and the Search for Identity, play a fundamental role in the construction of the subject’s identity. Augustus Short, Anglican Bishop of Adelaide and a good friend of Hale’s, certainly stressed the importance of dress code. Appropriate appearance and behaviour reflect, he claimed, a civilised and Christian interior life. On his first visit to Poonindie in 1853, Short was met at Port Lincoln by Hale and several residents from the institution. In his report to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, he made this sanguine comment about his Aboriginal hosts: ‘I was agreeably surprised to see them nicely dressed in the usual clothing worn by settlers; cheque shirts, light summer coats, plaid trowsers [sic], with shoes and felt hats – articles mostly purchased with their own earnings. They were better dressed than the labouring class in general at home.’

Short’s materialist take recognised the importance of environment in shaping character, bringing, in his words, Aboriginal residents at the institution ‘out of darkness into light’. Dress and decorum opened the gates to God’s domain. Writing on 7 February 1854 about the cricket match at St Peter’s College where Kandwillan took seven wickets, the newspaper correspondent for the South Australian Register paid particular attention to the apparel worn by the Aboriginal members of the team, noting: ‘They are smart lads, sporting their handsome white and coloured shirts, their gossamer coats and well polished shoes, in a way that speaks wonders for their industry and civilization – the former having supplied them with the means and the latter with the wish to obtain such luxuries.’

The journalist delivers a glowing tribute to the Poonindie ‘lads’ and to their absorption of middle class, acquisitive values – indeed the aspirations of the newspaper’s readership.

In Crossland’s portrait, Samuel Kandwillan has exchanged his cricket whites for the costume of an educated gentleman. He wears a high-winged collar with silk cravat knotted in a thick bow. Only the turned down points or ‘gills’ of his shirt collar are visible above the neck-tie. A buff-coloured frock coat with V-notch lapels is fitted close to his body and he is dressed in a shirtfront of white linen with vertical pleats and lapelled waistcoat. His smart side whiskers meet under the chin and his hair has been carefully waxed and flattened. Kandwillan clasps the Bible, with both hands, close to his waist.

On his visit to Poonindie, Short went on to describe the ‘native manner [as] naturally shy, reserved, and incommunicative, but gentle and unimpassioned’. The emotional qualities of Crossland’s portrait echo the Bishop’s observations. We know from a letter written by Mathew Moorhouse, the Protector of Aborigines, to Hale, the day after the cricket match at St Peter’s, that Kandwillan only stayed for one sitting and was anxious to make a hasty return to Port Lincoln. We can read this impatience in his restraint and diffident demeanour. Broad sections of paint thin enough to lay bare the weave of the canvas issue further evidence of the deftly completed artwork.

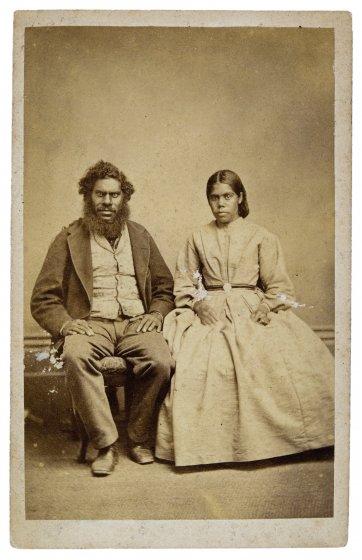

The recent discovery of a series of photographic portraits held in Hale’s papers at the Library of the University of Bristol and documented by historian Jane Lydon in Calling the Shots: Aboriginal Photographies, substantiates the Archdeacon’s desire to record the mission and its residents and confirm his role in status-making. His marketing talent is demonstrated by a decision to use the latest techniques of visual documentation. One of these remarkable portraits (from an unidentified photographer) is clearly of Kandwillan. An early example of the ambrotype, a relatively inexpensive commercial photographic process, it must date from the mid-1850s, before Hale’s departure in 1856 to fill the See (diocese) of Perth.

Kandwillan’s features are immediately recognisable in this photograph of a man radiating confidence and sophistication. He is seated on a high-backed chair, his left arm resting on an open book – the Bible? – placed on a side-table. Absent is the stiffness and shyness of the Crossland portrait; in this photograph Kandwillan appears relaxed and elegant, befitting his role at the mission. With his wife Martha Tandatko and nine catechumens, Kandwillan was baptised by the Bishop of Adelaide at Poonindie on 10 February 1853. One of the ‘trained scholars … of the Adelaide [Native] School’ wrote Short, Kandwillan ‘was capable of reading the Prayers and Lessons in the Chapel on Sunday mornings during the absence of the Archdeacon’, and with ‘so much propriety’ did he conduct the divine services, that settlers in the neighbourhood ‘used regularly to attend’. Indeed, Kandwillan’s competence and strong moral character are praised in reports from the mission. Acutely aware of the moral dangers represented by settlers on the frontier, the Bishop of Adelaide recollected in his published account of a much later visit to Poonindie in 1872: ‘The natives were moral in their conduct, and able to resist temptation when sent with drayloads into Port Lincoln. It is remembered how “Conwillan” on one occasion having loaded his own dray with goods from a coasting vessel according to orders, was found by the Archdeacon rendering the like service to a settler, whose teamster was lying intoxicated on the beach.’

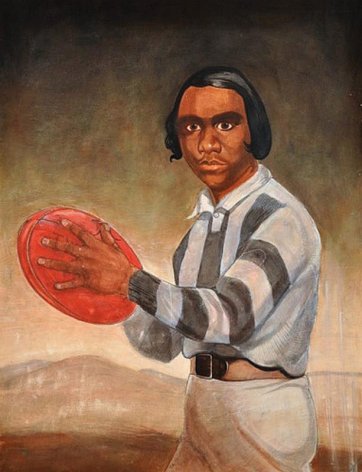

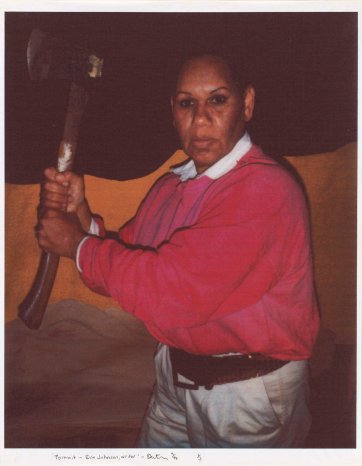

While the oil portrait of the lay preacher communicates well-groomed conservatism, the young John Nannultera strikes a heroic pose. His portrait has directly inspired artists and poets. Tim McMonagle has created his version as The Poonindie Footballer. The artist Destiny Deacon redefines the image in a photo portrait of writer Eva Johnson, and poet Les Murray pays homage to the sitter’s resilience in his poem ‘The Aboriginal Cricketer Mid-19th century’:

Good-looking young man

in your Crimean shirt

with your willow shield

up, as if to face spears

Murray’s image in these first lines from the poem points to the cross-cultural combat that was lived experience for these young men. They were the first generation of Aboriginal men growing up like ‘strangers in a strange land’, the biblical phrase borrowed by Tom Adams, one of the Poonindie residents, in a letter he wrote to the Archdeacon. The poet’s reference to Nannultera’s striped flannel shirt – sometimes referred to in the nineteenth century as Crimean shirts – under his crimson blazer, may also be an allusion to the war in the Black Sea peninsula which Britain entered the year the portrait was executed. In an emotive letter written to his Archdeacon on March 23, 1854, Bishop Short seethed: ‘All here [in Adelaide] breathes war, and a desperate war, for the powers of Steam and Artillery have given added oral power to the means of destruction. The Czar seems absolutely mad with ambition and fanaticism.’ Nannultera is the Christian crusader as sportsman.

‘Portraiture’, writes Pointon, ‘is poised between resemblance and transfiguration’. In a description of the portrait of Nannultera in Australian Pastoral: The making of a white landscape as ‘a figure of grace and humility’, art historian Jeanette Hoorn employs the image of the saint. The numinous beauty of the portrait is enhanced by the unearthly and minimalist quality of the landscape in the background, spreading its glow into a bruised cerulean sky. The painter achieves a remarkable balance between vigour and elegance in the athletic stance of his subject. Shapely buttocks, agile hips and rounded shoulders are revealed by his close-fitting clothes, soft leather belt and three-quarter profile. Transcendence is here circumscribed in masculine terms. His bearing, reminiscent of Greek contrapposto sculpture, reveals Crossland’s classical training, as does the confident modelling of his features and use of polished light falling on his forehead and youthful face.

Hale, a cricketer himself, introduced with enthusiasm this game for gentlemen at Poonindie, and the skill of successive teams is reported by visitors to the mission. The Bishop of Adelaide admired ‘their neatness in fielding and batting’ as well as their good humour and courtesy on the playing field. On the importance of the game in bringing Aboriginal people into the fold of masculine Christian civilisation, Short eulogises, ‘To those who have any doubts as to the identity of the manhood in the white and black-skinned races it may be satisfactory to learn, that the same hopes and fears, the same zeal for the honour of the Institution, the same pride in the cricketing uniform and colours, … animated on this occasion the quondam [ie former] denizens of the wilderness … proving incontestably that the Anglican aristocracy of England and the “noble savage” who ran wild in the Australian woods are linked together in one brotherhood of blood – moved by the same passions, desires, and affections.’

The passage crystallises the attitude of Hale, Short and many in the evangelical community, a view that recognised no essential difference between races – a view that would soon shatter in the wake of social Darwinism.

Vehicles for mission propaganda, these paintings of ‘redeemed natives’ serve to display the positive results of ‘civilised’ training and Christian teaching the two men received at Poonindie. While Kandwillan and Nannultera became models of discipline rendered socially visible by the art of portraiture – chaste heroes, if you will, of cultural accomplishment – the portraits are filled, nonetheless, with a poignancy and a stillness and a sense of the impenetrable.

Some elements common to the Poonindie portraits expose traces of their Aboriginal past. Kandwillan and Nannultera are set in a landscape. The low horizon brings the figures forward, lifting the ‘subjects out of time’ as Eve Buscombe described it in her study Portraits of the Aborigines, and Kandwillan’s backlit frontal pose against a cloudless sky, increases the sense of monumentality. The dull copper and yellow ochre colouring and surreal barrenness of the cricketer’s landscape is reminiscent of Russell Drysdale’s rusty palette in many of his outback paintings done a century later. Since the two men worked and lived on the land, this decision by Crossland references their status, yet no signs of agricultural activity can be detected, nor even clear indication of a human presence in the landscape. Has Poonindie as part of the rural economy been replaced by an attachment to Country?

For Nannultera and Kandwillan, they are not (only) handling props,

but cultural weapons. Kandwillan clutches the Bible close to his body; Nannultera’s grip on the cricket bat is firm. Their object-ness gives them confidence: a game of cricket is won or lost, and faith cannot be stolen. In 1854, the year the portraits were painted, the Poonindie community, wrote Hale in the Adelaide Times on 27 February, was engaged in a struggle, and its residents ‘living examples of what man is when struggling to emancipate himself from the fetters of sin, and the bondage of former evil habits’. Hale recognised the strength but also the intense vulnerability of his project. In many ways, the process of assimilation is a reflection, not of passivity, but of Aboriginal people’s ability to sustain a presence and determine a revised future within the colonial settler culture that was so swiftly replacing their own: a strategy of resemblance rather than the repression of difference.

Hale certainly intended the two portraits to complement one another. Samuel Kandwillan, a catechist of the Natives’ Training Institution, Poonindie signifies achievements of the mind and moral character. Nannultera, a young cricketer of the Natives’ Training Institution, Poonindie signifies physical attributes and accomplishment in sport. Indeed, besides wheat, moral discipline and cricket were Poonindie’s most notable exports. While the portraits may have functioned as role models for the residents if they were on view at the mission, the paintings stayed in Hale’s possession, remaining with him until his death in 1895.

The portraits also tell a story about their benefactor standing in the shadows of the mounted canvas. They authenticate his pastoral work and indicate Hale’s genuine affection for and lifelong commitment to the residents of Poonindie. Evidenced by his book, The Aborigines of Australia, being an Account of the Institution for their Education at Poonindie, in South Australia, Hale considered the mission his greatest achievement. Like Short, he revisited it in the 1870s and was deeply saddened to hear of its demise only a few weeks before his death. In his last letter to the ‘dear people lately belonging to the Poonindie mission’, Hale encouraged them to ‘let it be seen by the holiness of their lives that they had once belonged to the mission’. Many nineteenth-century images of Aboriginal people were intended as records of a dying people – an ante-mortem analysis of a moribund race, as artist and critic Blamire Young once expressed it. Hale’s social experiment, radiating light rather than pessimism, finds visual expression in these portraits of a lay preacher and cricketer. In a letter dated 31 December 1850, Hale set out his thoughts on the destiny of his pupils. Once they had absorbed the teachings of Christ he would, without wishing to retain residents on the mission, ‘permit them to go forth beyond the reach of our influence, just at the moment when it is, more than ever, important that the influence acquired should be turned to good account’.

Rather than colluding with the mood of his times and accepting a role for Aboriginal people as bystanders in their own country, Hale’s vision, echoing Short’s ‘brotherhood of blood’, aspired to a fraternity promoting Aboriginal Australia’s welfare and pride, albeit on his – Christian – terms. In her book of essays Romanticism and its Discontents, novelist and art historian Anita Brookner once used the phrase, ‘this is not Art as consolation, so much as confirmation’. A similar determination no doubt motivated Hale to commission these paintings. These visions of harmony and strength – spiritual and physical – confirmed the present and, importantly in Hale’s mind, would herald a bright future.

The two portraits entered the collection of the National Library of Australia from the London-based New Zealand-born collector Rex Nan Kivell. In recognition of the work’s aesthetic and cultural significance, Nannultera’s portrait is today on permanent loan to the National Gallery of Australia. In Belonging: Stories of Australian art, which reconsiders cross-cultural conversations in Australian art, the works are reunited – the ghosts of Poonindie would have something to celebrate. While Hale’s hope for the integration into colonial society of a Christian Aboriginal community never materialised, through their portraits, the catechist and the cricketer have found voices of their own, not forgotten.

Related information

Portrait 65, Autumn/Winter 2021

Magazine

Hugh Ramsay, the fashion of Jenny Kee and Linda Jackson, Peter Wegner's centenarian series, John and Elizabeth Gould's family connections, Karen Quinlan's top five portraits and more.

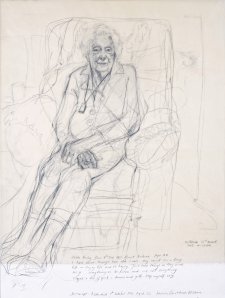

Drawn from life

Magazine article by Penelope Grist

Penelope Grist discovers the rich narratives in Peter Wegner’s series of centenarian portraits.

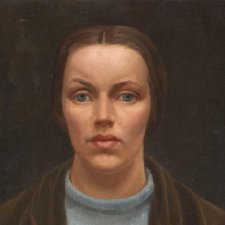

Give me five

Magazine article by Karen Quinlan AM

National Portrait Gallery director Karen Quinlan AM nominates her quintet of favourites from the collection, with early twentieth-century ‘selfies’ filling the roster.

![Man of Poonindie Aboriginal Mission – probably Samuel Conwillan [Kandwillan] – South Australia, c.1855 Man of Poonindie Aboriginal Mission – probably Samuel Conwillan [Kandwillan] – South Australia, c.1855](/files/6/1/3/e/i15077-th.jpg)

![Poomindie [Poonindie] Mission Station, 1853 William Dickes Poomindie [Poonindie] Mission Station, 1853 William Dickes](/files/b/6/5/a/i15087-th.jpg)