‘If you want to convey fact, this can only ever be done through a form of distortion. You must distort to transform what is called appearance into image.’

Francis Bacon

Alter ego

by Tom Fryer, 6 July 2021

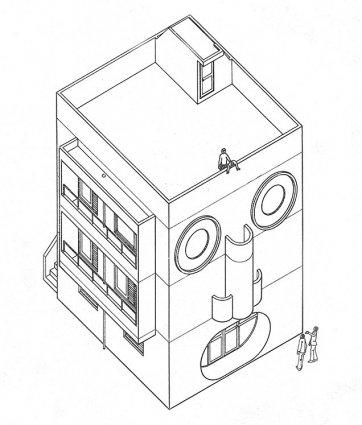

The representation of human form has a long history in western architecture. The ancient Roman polymath and military engineer Vitruvius described the human figure as the principal source of proportion informing the part-to-whole relationships of any work of architecture. This abstract translation of the human body into built form has been explored – deploying varying grades of literalness – through time, from Vitruvius, to Claude Nicolas Ledoux’s conceptual infrastructure projects for the Ancien Régime in France, to Kazumata Yamashita’s comedic Face House in Kyoto in the postmodern period.

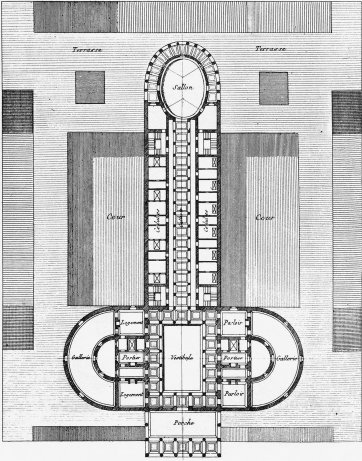

The distant epoch and lack of accreditation makes representation in Vitruvius’ own architecture impossible to know. However, as we arrive at the neoclassical period, the timeless notion of the portrait is perceptible in the architectural thinking of the day, along with an increasingly blurred line between architecture and the self-representation of the architects themselves, in all their output: structures, drawings and self-promotional efforts. For his part, Ledoux was the foremost advocate of architecture parlante (‘speaking architecture’), where the function of the building is expressed by an abstracted, often anthropomorphised symbolism. Ledoux’s range spanned the authoritarian – spherical buildings representing all-seeing eyes and proposed as gamekeepers’ houses – to the erogenous (his phallic floorplans for brothels are more direct in their meaning).

But it is Ledoux’s self-image that warrants particular analysis, with Martin Drolling’s 1790 portrait presenting the man, as if caught mid-joke, with a familiar and open smirk that gives some suggestion of the mind that saw architecture parlante as a vehicle for utopian plans. The style of the painting is disarming, informal and compositionally rakish – compelling, perhaps, to prospective clients attracted to such values. If we consider this portrait of Ledoux as a form of self-promotion, the parallels between the image of the man and his architecture exist, but are oblique: nuanced and open to interpretation.

The field of architecture today, on the other hand, sees its prominent global practitioners controlling their image as carefully as a politician might, to project radicalness, iconoclasm, or genius. The managed image of the architect has been integrated into the work of their firm, and vice versa: a seamless package that reiterates a singular attitude, with total consistency between the image of the practitioner and the image of the practice.

It wasn’t always thus in the modern era, which gave us an intriguing cast of architects whose lives and practice were no less interwoven, but who displayed a more varied, less singular, and sometimes perplexing distance between the representation of the person and their work. It’s revealing to consider these practitioners through the lens of the portrait, for while the discipline of architecture has no practical function for the portrait in practice, the twentieth-century architect often turned to portraiture in their drawings, in their myth-making, and in their built work.

The early modern era in architecture played out in the parallel theatres of the United States and Europe, with minor sideshows, including Australia. The lodestar of modern American architecture in the early twentieth century was Chicago architect Frank Lloyd Wright, and his public image presents a striking consistency between the work of the man and the image of the man through time. Wright’s ‘prairie’ houses were exuberant in their material detailing, carefully spatially planned for drama, and with a horizontality that spoke to Chicago’s place at the edge of the Great Plains. Similarly, the young Wright’s own style was theatrical: floppy bow ties, red-lined capes and wide brimmed hats that suggested a view to the horizon.

But as Wright helped shape (and navigated) the boundaries of how contemporary architecture was increasingly defined – stripped of ornament, enamoured of the expansive white plane, and wed to notions of material honesty – his own personal representation too was increasingly pared back. In a 1959 site photograph, as his Guggenheim Museum neared completion in concrete (Wright’s initial concept has been for red stone, or brick), the modern project was well under way, and Wright himself presented the wizened gravitas of a master who had abandoned his youthful flourishes, and who would die before the building opened to the public.

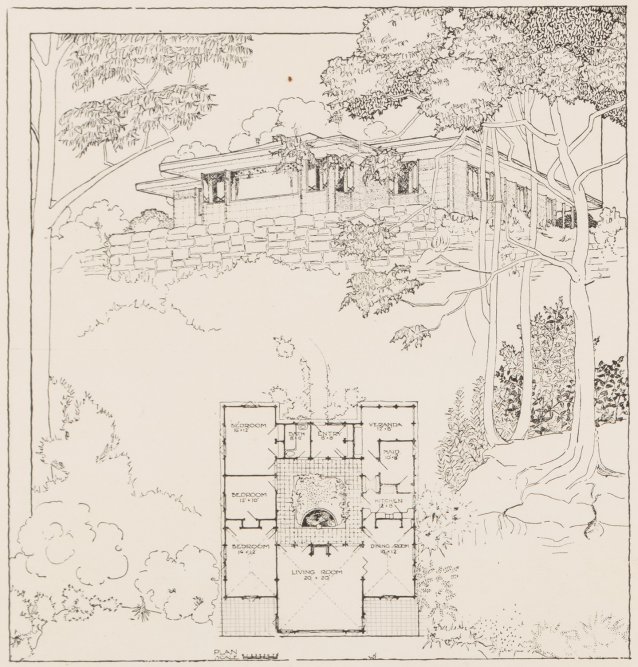

The vibrancy and originality of Wright’s studio set many careers in motion. Two young architects who had met in Wright’s office entered and won the architectural competition for the design of the new capital city of Australia. Marion Mahony Griffin’s masterful, muted renderings of their proposed scheme had somehow captured the dun tones of Canberra from distant Chicago, while her linework softened and made organic the strong geometries of their urban planning. Marion and husband Walter Burley Griffin’s 1911 plan for the city brought them to Sydney in a singular injection of culture to the new nation. The Griffins adopted Australia with passion, interweaving their North American identities, preoccupation with design and aesthetics, and interest in the occult, with the novel, fertile natural and cultural character of Sydney.

Marion’s work in Australia in particular – of which architecture was only a part – saw her expand her portfolio of remarkably attuned representation, introducing layers of environmentalism and spirituality to her art. Even more than Canberra, the Griffins’ design for Castlecrag – a ‘model residential’ suburb on Sydney’s Middle Harbour – is a portrait of place, conceived through the couple’s reverent exploration of the rocky Sydney Harbour cliffs and beaches, and informed by their emerging convictions on preservation and conservation. Marion’s silk drawings for Castlecrag are extensions of these principles, putting forth a restorative vision for the denuded and degraded site, and unified compositionally in the Japanese style she had honed in Wright’s office. Her striking plans for a rusticated courtyard house with a native garden at its centre was not only ahead of its time in its embrace of the dry ecosystem, but emblematic of the identity of the designers, a portrait of a future place to be borne of deeply personal ideals, arranged around the beloved alien flora of their adopted home.

In the 1920s the International Style emerged in Europe, with Swiss architect Le Corbusier a leading proponent. The movement was born out of the ashes of the First World War, and came with an entirely radical agenda for a rational, mechanistic architecture that spoke to the era. Le Corbusier epitomised its design sensibilities; his Five Points of Architecture would become a manifesto for generations of architects who rejected ornament, embraced expansive glazing and expressed structure. Le Corbusier’s work is genuinely radical – from his treatment of working drawings (which reflect the compositional experiments of contemporaneous painting and sculpture) – to his use of materials, incorporating extreme originality, refinement and honesty.

And what of the man himself?

The photographic record is striking in the disconnect between the architecture and the person. While Le Corbusier seems completely liberated as a practitioner, he appears sartorially confined by his time. His tweed three-piece suits, bow ties and sensible shoes recall a teacher – perhaps a headmaster – on a cruise. So when we look at his masterworks, such as the Villa Savoye in France, it is tempting to understand the building as realising a portrait of the man Le Corbusier understood himself to be – a radical, unprecedented expression of total modernity.

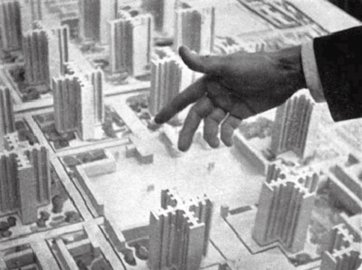

Perhaps his most representative image was both design and portrait. In a frequently reproduced photograph for his 1925 Plan Voisin, the architect’s disembodied hand, both elegant and claw-like, gesticulates over a Paris to be erased and repopulated by his giant cruciform towers.

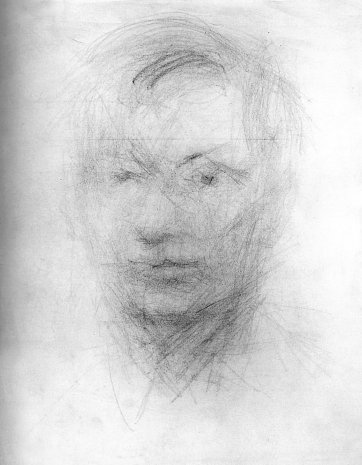

In the wake of Le Corbusier and other unreconstructed continental and American modernists, there emerged the architectural rationalists. In the US, Louis Kahn brought an agenda of pure geometry to his work, while stepping away from the pristine, machinic materiality of early modernism to a more expressive use of traditional materials. Kahn was a prominent practitioner in his time – a cerebral, academic presence with a prolific output, celebrated by his peers and awarded high-profile commissions around the globe. Kahn’s private life was complex. His face had been transformed by a childhood fire into a rictus of scar tissue, lending him an inscrutable rigidity, which, along with his Eastern European Jewish background, made him an outsider from early on. During his career Kahn maintained a series of real and long-term relationships with female co-workers and colleagues; they resulted in three children born outside of his first and enduring marriage. He lacked business acumen – he died in debt – and his dishevelled body famously lay unclaimed in a New York City morgue for days after he died of a heart attack in a public toilet in Penn Station. It is tempting to understand Kahn’s quest for purity of form, geometry and stability as counterpoint to a chaotic life. But the architect’s life and work can also be understood as more continuum and less binary; against a backdrop of the sexual revolution this unconventional man navigated his own late-realised potential and the entry of talented female collaborators into his realm. Kahn was intrigued by the ancient and by ruins; his structures and even his own self-portrait remind us that life revolves around frameworks that are not always fully defined, but which mesh together to define discrete moments in history.

Alison and Peter Smithson, another husband-and-wife studio, sought to confront London’s social challenge of the era – a shattered East End dating from the Blitz and a changing economic future for Britain – through housing projects constructed at a scale intended to renew vast swathes of the city. Curiously, their thinking led them to design predominantly concrete megastructures that eventually came to epitomise another set of social challenges for a generation of Londoners that grew up on housing estates. But the urgency of the social agenda actually pursued by the Smithsons is writ large in the perspective drawings of their housing projects. These are a portrait of a future Britain, no longer defined by the stoic wartime mentality, but inhabited by young cockneys demanding a modern backdrop on which to build a life. For all their subsequent problems, the proposals of the Smithsons were rooted in deep research and an intimate local understanding of the old ways in which communities had developed in the East End, and of character of the architecture and urban spaces that supported these communities. In this way, their perspectives are a portrait of an old London recontextualised and hurtling toward the end of the twentieth century.

The long, drawn out finale of twentieth-century modernism saw its final incarnation in a total repudiation of the then half-century old and increasingly misinterpreted legacy of Le Corbusier. Yet in the 1960s the postmodern era saw architectural radicalism assume the uniform of the east coast academic. Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, who worked assiduously to reconcile the staid and elite discipline of architecture with an interrogation of America’s social foundations, developed a portfolio of work that conjured freedom, lack of dogma and a recognition of everyday American culture as equal to fine art. Tired of the self-serious preaching of modernists and in parallel with pop art, they inverted the gospel of the modern era as an expression of the right to free thought and a sense of humour. But like Le Corbusier, Venturi and Scott Brown were sartorially normative. Venturi was reliably bedecked in brown suits and tie. Scott Brown’s increasingly conservative appearance saw her morph from go-go girl in her seminal 1966 Las Vegas portrait, to Laura Ashley-esque Sunday dresses in the 1980s, all the while developing a body of work of manifest originality that fundamentally questioned the discipline of architecture. Expectations and conventions, for Venturi and Scott Brown, were best defied – an attitude that recalled Ledoux and the promise of a practitioner who delights in challenging, cajoling and surprising the client.

The commonality between all these practitioners might have been instinctual: that architectural practice, and life, and image, are interrelated. But the relationship between architect and image was rarely a simple facsimile. Rather, those architects who elect to insert themselves into (or outside of) the drawings tend to see themselves as part of the project, as expression of a person, as embodiment of a thought or a moment or a movement; and as an element to be redesigned, reconsidered, refined. As Bacon understood, the project of modernism in the twentieth century owed as much to distortion as to fidelity, and an expanded understanding of portraiture layers colour, sweat and laughter over last century’s grand movement between the mind, the plan and the building.

Related information

Portrait 65, Autumn/Winter 2021

Magazine

Hugh Ramsay, the fashion of Jenny Kee and Linda Jackson, Peter Wegner's centenarian series, John and Elizabeth Gould's family connections, Karen Quinlan's top five portraits and more.

Wunderkind lost

Magazine article by Inga Walton

Inga Walton on the brief but brilliant life of Hugh Ramsay.

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!