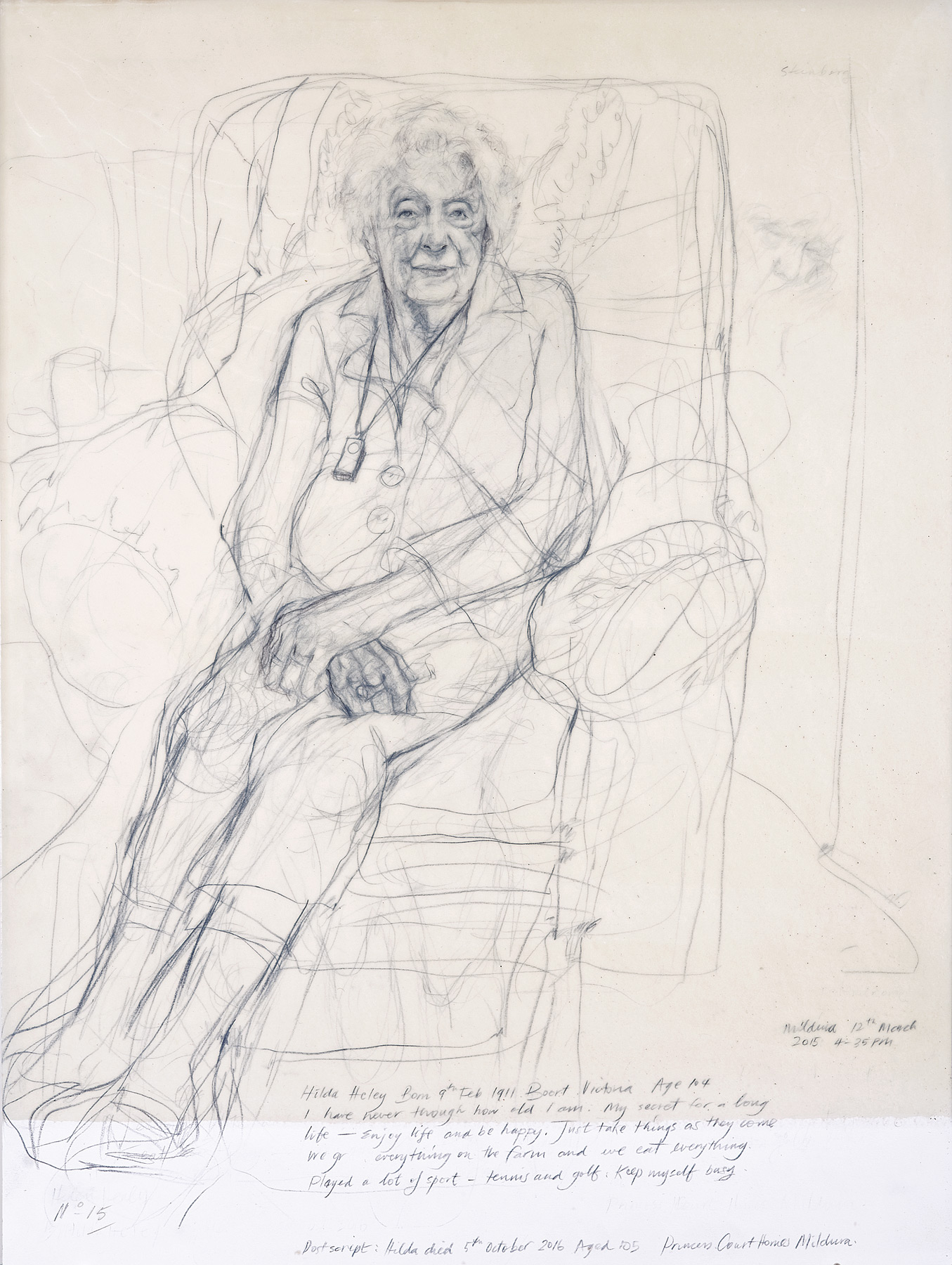

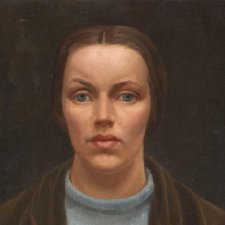

Hilda Heley, 2015 Peter Wegner. Collection of the artist. © Peter Wegner

‘I don’t know where the last hundred years have gone!’, exclaimed 104-year-old Mildura resident Hilda Heley, as artist Peter Wegner sat drawing her portrait on an autumn afternoon in 2015. It’s a nice mix of deadpan centenarian wit and earnest reflection: living to a hundred is a fascinating concept, emphasising both defiant dalliance with the bounds of the human lifespan, and the temporal milestone of a century alive.

Six years on, Wegner’s ongoing centenarians series numbers – appropriately – almost 100 portraits. The project grew out of his visits to his Aunt Rita, who lived to 104; they would have a cup of tea, and he would draw her. When Wegner gets in contact with a centenarian, he visits for two or three hours, armed with a cake to share, off-white paper, and ten sharpened blue-grey Derwent pencils: ‘I don’t want to waste time sharpening pencils; I lay them out and get through all ten every time… They have a cup of tea and chat the whole time … I interview, using drawing as a medium.’

1 Arthur Atkins , 2020. 2 Keith Kellar, 2020. 3 Alice Eastwood, 2020. All Peter Wegner.

Collection of the artist © Peter Wegner

How does an interview manifest in a portrait? Wegner’s incorporation of inscriptions into the works reflects the conversation, while also evoking the palimpsest of memory. For example, in his portrait of Arthur Atkins, the name and details appear faded except for the statement, ‘I did 31 trips in the Lancaster Bomber’, presenting a powerful personal narrative, and the achievement of simply surviving (half of all Lancasters were shot down over Europe in the Second World War). Some notes situate a life in world history: Alice Eastwood, born during the First World War, remembers the days of horse and cart, the Harbour Bridge being built, and the Second World War. Others combine personal and world history: Keith Kellar served in the Middle East and New Guinea in the Second World War, but his first job was scaring cockatoos off crops for 14 shillings a week.

As a portrait painter, Wegner is fascinated with body language: ‘The way someone sits down can show the whole character of the person’. He just asks them to sit comfortably and move as they like, most often taking the first pose they sit in. ‘Sometimes an arm or hand will move and I’ll erase and move, but I like the traces of the previous line to remain and preserve the process of drawing from life.’ As with recollections, details in these portraits float in and out of focus, and the sharing of a life story resonates in the portraits’ dynamic mark-making and erasures.

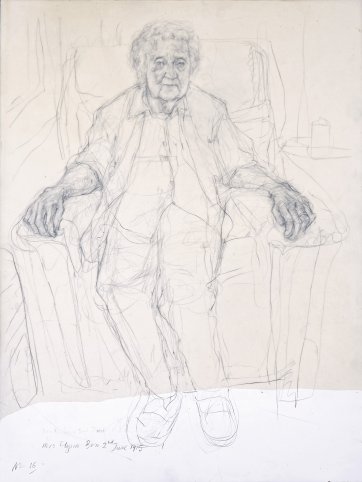

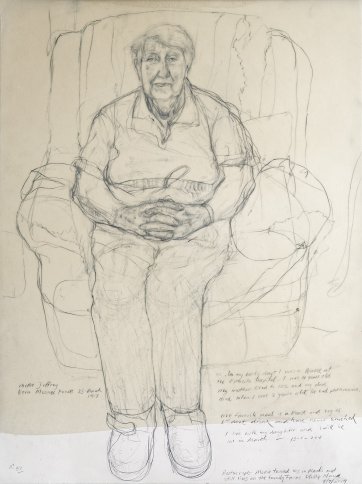

1 Mrs Flynn, 2017. 2 Mollie Jeffrey, 2018. Both Peter Wegner.

Collection of the artist © Peter Wegner

When people speak, most often the greatest animation occurs in the face and hands. These are Wegner’s starting point and focus. Mrs Flynn’s hands, for example, show the texture and gentle angles under skin thinned with age. In all of the portraits the gaze of the sitter is direct, with expression on the warm side of neutral – they are not posed faces but they do convey character. Former nurse Mollie Jeffrey’s warmth leaps of the page through Wegner’s careful attention to the form, line, and texture of her eyes, lips, hair, fingers and collar. The direct gaze is not challenging or uncomfortable because of the energy that emanates in conversation. The face and hands often remain the only fully developed features in the final portrait – another way these works stay true to the concept of a drawn interview.

1 Erwin Fabian, 2017. 2 Marg Mossop, 2015. Both Peter Wegner.

Collection of the artist © Peter Wegner

Rather than appearing as romanticised figures, these centenarians are arrestingly real. Each portrait conveys a powerful sense of human presence, even when their story is as dramatic as Erwin Fabian’s. He was a refugee from Nazi Germany who escaped to England, only to be transported to Australia aboard the Dunera and interned at Hay and Tatura. (The Portrait Gallery holds Fabian’s portraits of fellow internees Kurt Baier and Fred Gruen.) There is a relaxed intensity in Fabian’s pose and gaze, which is almost indirect – but with a movement in the eyes that catches you. As full-length portraits, Wegner’s point of view and inclusion of clothes and furniture lets us sit alongside him as he listens.

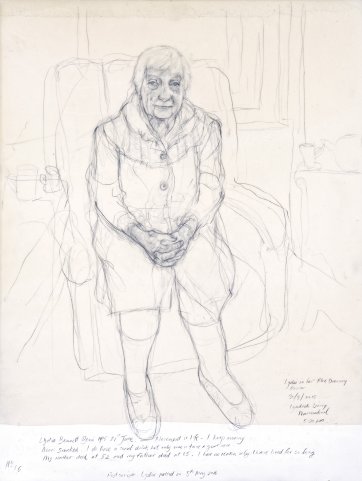

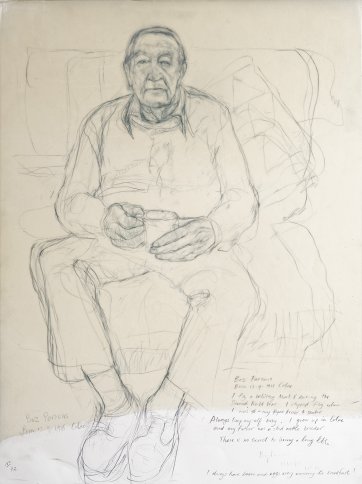

1 Lydia Bennett, 2016. 2 Boz Parsons, 2019. 3 Myrtle Hooper, 2019. All Peter Wegner.

Collection of the artist © Peter Wegner

‘I feel so good about life when I come out of these conversations – every time, I have learnt something about them and about myself’, he reflects. ‘This is reaffirming to life.’ The only thing Wegner adds to the portrait post-sitting is a memorial postscript. The artist admits that ‘in an odd sort of way I’m still trying to find out how to live to 100’. He always asks his sitters this question and often includes the answer in their portrait. For Fabian it’s being ‘keen on your work’; Lydia Bennett says ‘movement is life. I keep moving’. In Mildura, Hilda Heley told Wegner, ‘Enjoy life … Just take things as they come.’

Peter Wegner’s portraits subvert any concept of centenarians as individuals invisible behind the mystique of defied mortality. Through the interview transcribed as portraiture, each centenarian appears as a living, breathing link with history – someone who has visited that ‘foreign country’ of the past where, as the old L P Hartley quote has it, they ‘do things differently’.