It was not just the physical fit that appealed – the jacket also aligned with my identity at the time. Military uniforms signify order, conformity and discipline; however, this was not the resonance I was after. It was more of a tenuous connection. My father joined the navy in 1927 when he was fifteen, and stood at just five foot one. He was discharged in a very poor state of health in 1945 at the end of the Second World War. Archival records show he had grown to five foot four post-enlistment. He would never have worn such a jacket in his long naval career; he only made it to an able seaman rating.

As an embroiderer, the gold braid lured me. The lower band was very wide with a narrower upper braid curving into a circle on the outer arm. I thought about removing the braid and buttons, but then it would just be a dark blue jacket. On close examination there were small holes on the shoulders where other insignia had been removed. A label was sewn onto the inner lining: ‘Quality clothes by Swedex Sydney’.

Dressing for an exhibition opening that night in front of the mirror at home, I negotiated with my reflection: I needed to strike a balance between dressing appropriately and fitting in, as well as looking and feeling like an artist. Dressing is the moment when social expectations and personal preference come together; it’s a reconciling of sorts. The wearing can be a fleeting moment – an hour or so mingling at an exhibition opening – or for an entire career. For those who dress in military uniforms every day, there is little of the ‘wardrobe moment’; that is, the internal dilemmas and anguish evoked when the wardrobe door is opened. For them, the decisions about what to wear have already been made. There in my bedroom, at that moment, I was able to make a choice.

When bound to wear a military uniform there is no exclamation of having nothing to wear. When civilians experience this, it generally means there is absolutely nothing in the wardrobe that matches the specific identity sought for the occasion at hand. Our identities shift over time and place. Dress is a key expression of those multiple identities we all have.

Dressing can be seen as a game: demonstrating agility with clothing a body, fitting in with peers, or even standing out – as well as acknowledging those on the sidelines. According to writer Gregory Stone, letting the spectators know ‘what game they are watching’ as we pass by is important. Anthropologist Karen Tranberg uses the term ‘clothing competence’ for the way people expertly bricolage their bodies when dressing up in their various identities.

For those who wear uniforms, particularly military uniforms, decisions on dress evaporate. Military uniforms can signal national wealth and taste, esprit de corps, cultural notions of gender, tribal loyalty, physical strength and stylistic notions of expression. The list might also include neatness, entertainment, conformity and sexual attraction. Depending on the cultural and political associations with the uniforms, membership of the military may also be seen as supporting particular political ideologies or regimes. Cultural theorist Jennifer Craik reminds us that the role of uniforms has also been deliberately appropriated in a range of transgressive and subversive contexts, such as pornography, prostitution, sado-masochism, transvestism, cross-dressing, vaudeville, mardi gras, singing in choirs and performing ‘strippergrams’. Intriguingly, the uniform can take the form of a fetishised cultural artefact embodying erotic impulses and moral rectitude.

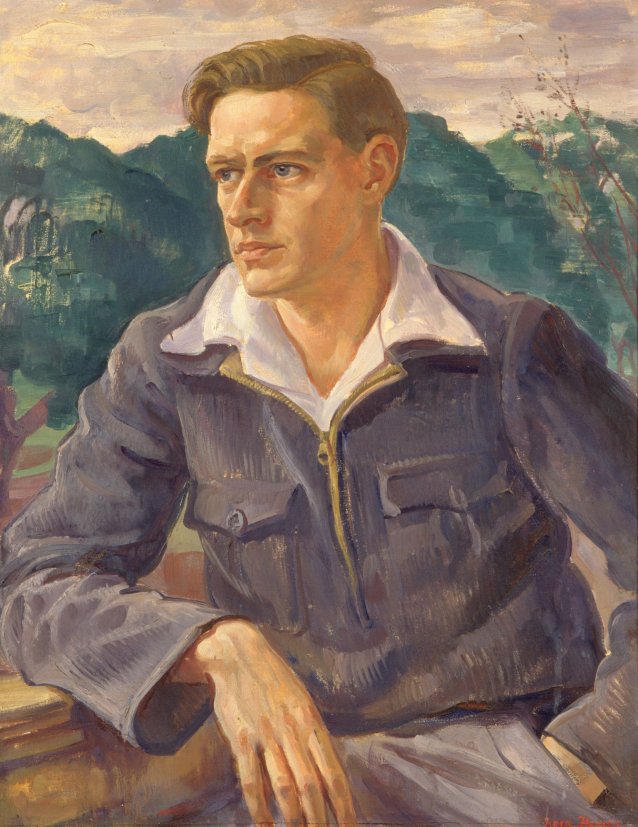

A military uniform is not just the imposition of dress, but the acquisition and long term implications of what anthropologist Marcel Mauss calls ‘techniques of the body’. These techniques are necessary to function successfully within the military, whether the subject is male or female. The constant and repetitive training becomes ‘second nature’, and is carried over, or at least traces remain within the body. The stance and gait of soldiers are indicators of such traces. Correspondingly, in an artistic context, capturing the ‘second nature’ of the sitter contributes to the success of a portrait.

The uniform comes with certain codified behaviours. The salute, the click of the heels and the automatic verbal responses all reflect the machinery of power entering the body. These techniques of the body can last beyond the career dressed in uniform, and continue to be absorbed into one’s civilian identity. The combination of uniform outward appearance with specific, culturally contingent body movements is an archetypal symbol of military culture.

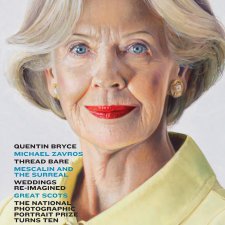

Wandering through the galleries of the National Portrait Gallery, there are a number of portraits of people in uniforms, many of them military. Audiences arrive at the Gallery with some understanding of what military uniforms signify. For those outside the military, the subtleties of uniform and decoration cannot always be easily interpreted. However, the concept of military dress as a metaphor for the state and authority is understood. The clothing, brass buttons, badges and rank markings of the institution do not represent the individual. The wearer of the military uniform is always on show, whether in actuality or through images. The bearing, pose and action of these people are the subject, just as much as the fetishised objects, such as metal insignia and clothing. In the contemporary world, dressing in a military uniform for a portrait, a moment in time, an identity in time, presents interesting challenges: the individual interior world versus the institution.

It is illuminating to consider the uniforms portrayed in the Portrait Gallery’s Robert Oatley Gallery, which is grounded in the theme of encounter between Australia’s Indigenous people and Europeans, and the establishment of the Australian colonies. There are numerous portraits of men in uniforms – dress that played a key role in the colony, and, at times, acted as an organisational device. With no built environment, dress acted as a management tool. Essentially, in the early days of the colony, it was a military establishment. The various uniforms of convicts and the Royal Marines delineated who held power.