A baby stares openly at whatever interests him: it’s one of the cutest of all baby characteristics. As the baby is tamed, domesticated and incorporated into the machinery of the State, however, he has to be taught that staring is rude. As time passes, he’s told to look people in the eye when shaking hands, not to look sideways at the trough, not to adopt an expression of ‘dumb insolence’ in the classroom, and – should a job interview eventuate – to meet his interlocutor’s eye, but not all the time. Throughout life, the degree to which we’re meant, and not meant, to look at other people is difficult to calibrate (and all over the world, it’s a different calculation for men and women, the affluent and the impoverished, the hale and the frail). Everyone knows it’s a survival skill, though. Amongst adults, the question ‘What’re you lookin’ at me for?’ is shouted more often than it’s couched as a courteous enquiry.

A perennially attractive feature of portraits is that we can stare blatantly and hard at them for as long as we like. Sometimes the person in the portrait will be looking away; and then it can feel as if we’re watching them in secret – tenderly, furtively, hungrily. Other times the person in the image may be staring right back at us. Then it’s the kind of standoff that might end, were both of us real, in a punch, a serious question, or a sudden, game-changing kiss.

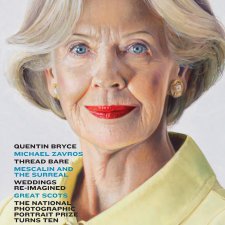

Occasionally, in photographic portraits as in painted and drawn ones, we sense an exciting connection between artist and sitter. In my own favourite photographs from ten years of the National Photographic Portrait Prize, which include a self-portrait, the sitters acknowledge what’s going on. They can look bold or nervous, appraising, forbidding or seductive, but they have to be palpably present, giving off human warmth and the certain knowledge they’re being photographed. Unless, of course, they’re dead, which several subjects of the NPPP have been.