Amid the twentieth century socio-political turmoil that fomented war across the theatres of Europe, and then Asia and the Pacific, the drive to understand the psychological impulses of humankind crystallised through experiments in medical treatment and psychiatry.

Theories of the unconscious, proposed by the Austrian medical scientist Sigmund Freud, had been explored by doctors working with soldiers traumatised by their experiences of combat during the First World War. Freud hypothesised that deep thought processes are responsible for our reactions and emotional responses to people and events, and that they drive our psychological needs. The behaviour and private thoughts of numerous individuals studied by Freud confirmed for him the presence of an unconscious mind that acts of its own volition, continually interacting with the conscious mind of everyday thought. Freud theorised that the unconscious mind throws up unwanted thoughts and urges that we might want to repress, and, through psychoanalysis, repressed thoughts and emotions could be analysed and treated.

In Australia, John William Springthorpe was fascinated by the potential that Freud’s psychoanalytic models held for the recuperation of soldiers shaken and debilitated by the mental and physical impacts of war. Springthorpe lamented that medical personnel were ‘unacquainted with psychopathic manifestations or their proper treatment’. In 1930, Roy Winn, who had served at Gallipoli and in France, wrote in the Medical Journal of Australia that physicians required as sound a knowledge of psychology as of physiology to effectively treat shell-shocked soldiers. Psychoanalysis, he wrote a decade later, could relieve ‘deeply buried emotions, such as guilt concerning the impulse to kill’.

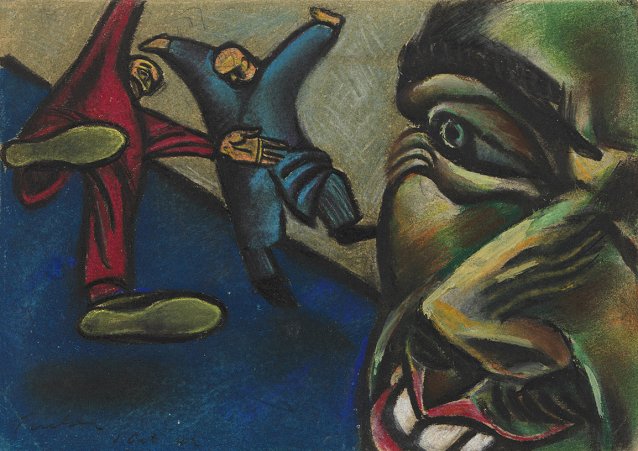

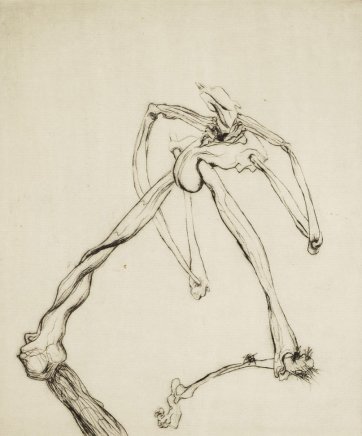

The idea of subconscious impulses appealed strongly to artists inspired by the aims of Surrealism. In France, writer André Breton had gathered a group of like-minded poets known as the Mouvement Flou. Two years later, in 1924, he set out a manifesto for the aims of the group who were now self-proclaimed ‘Surrealists’. Inspired by Freud’s ideas about unconscious thought processes, Breton stated that Surrealism seeks to express ‘the real functioning of thought’ using the arts as its medium. His Bureau of Surrealist Research sought to ‘gather together all possible communications relating to the forms which the unconscious activity of the mind is liable to assume’. In 1925, Galerie Pierre in Paris hosted the midnight opening of the first surrealist exhibition; it included artworks by Hans Arp, Max Ernst, Pablo Picasso, Man Ray and Giorgio de Chirico. The selection of artists reflected Surrealism’s male-focused origins. Later, in 1936, several women were included in the International Surrealist Exhibition in London: it included artworks by Briton Eileen Agar, Argentine Leonor Fini, Frenchwoman Dora Maar, German-Swiss Meret Oppenheim, and the mysterious ‘Jacqueline B.’ David Gascoyne was a member of the English organising committee for the exhibition; he translated André Breton’s preface for the catalogue, and his book A Short Survey of Surrealism became available in Australia that same year.

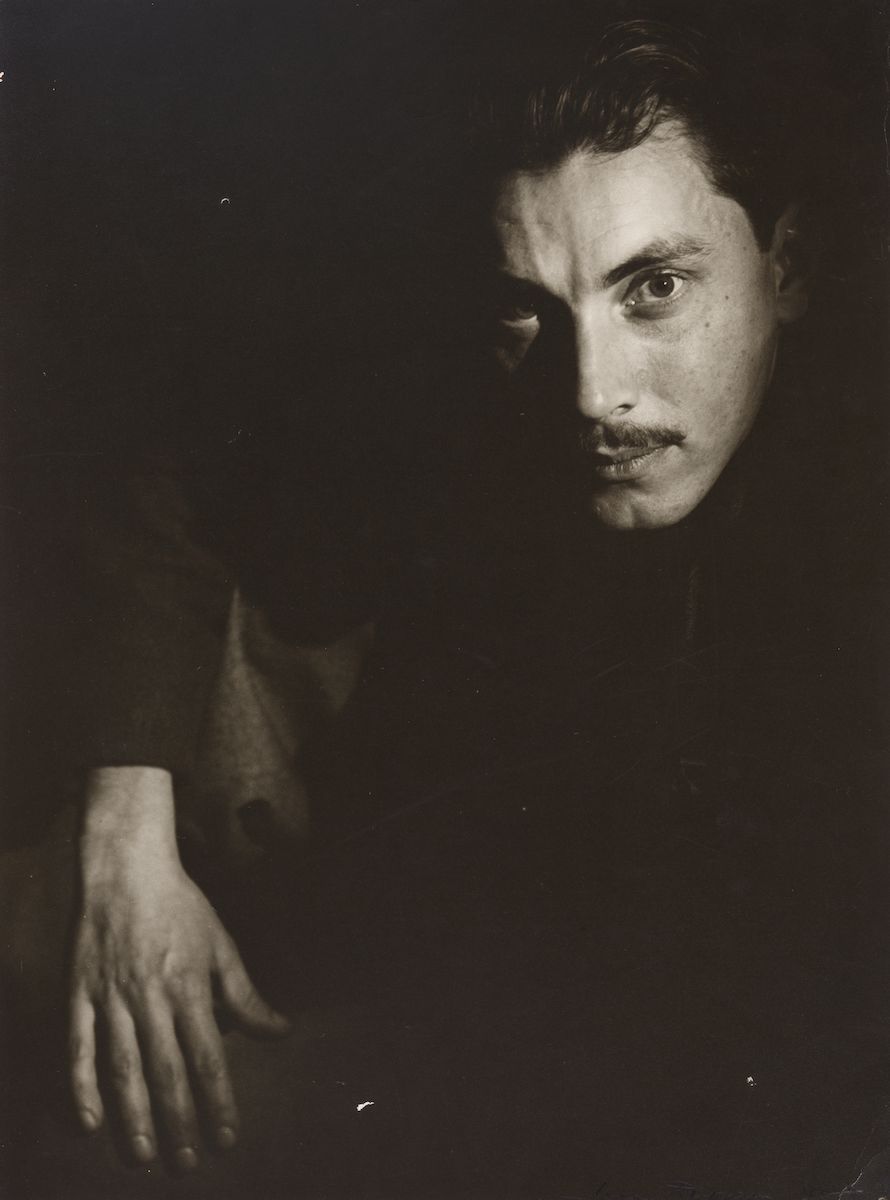

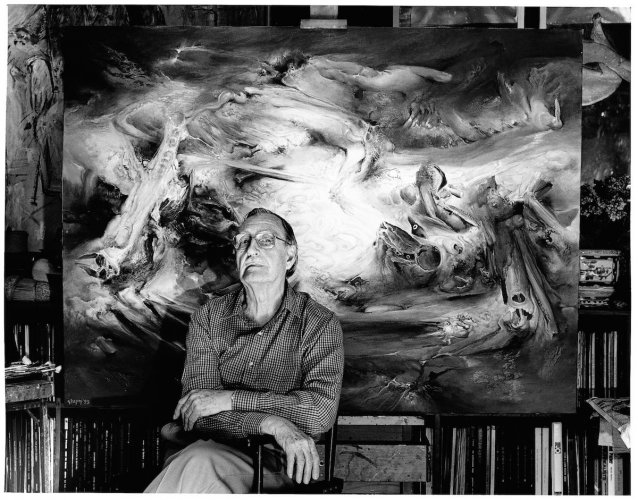

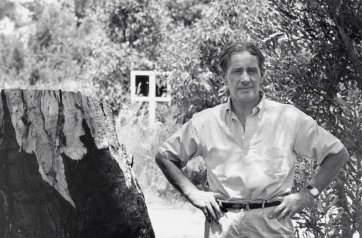

Australians Geoffrey Graham and James Cant were in Britain in the 1930s and they showed their work in surrealist exhibitions in London in 1937 and 1938, alongside their European contemporaries. The enigmatic, fantastical and absurd imagery of surrealist art had gained stylistic cachet even in Australia by the late 1930s. In 1940, Australian painter and writer James Gleeson (then aged twenty-four) described the movement for his local audience: ‘Surrealism is the word that is applied to those forms of creative art which are evolved not from the conscious mind, but from the deeper recesses of the sub-conscious. The theory of surrealism is based upon a belief that the logical mind, with its prescribed formulas of thought, is incapable of expressing the entire range of human experience and aspiration. To express such a range, the complete mechanism of the human mind must be used.’