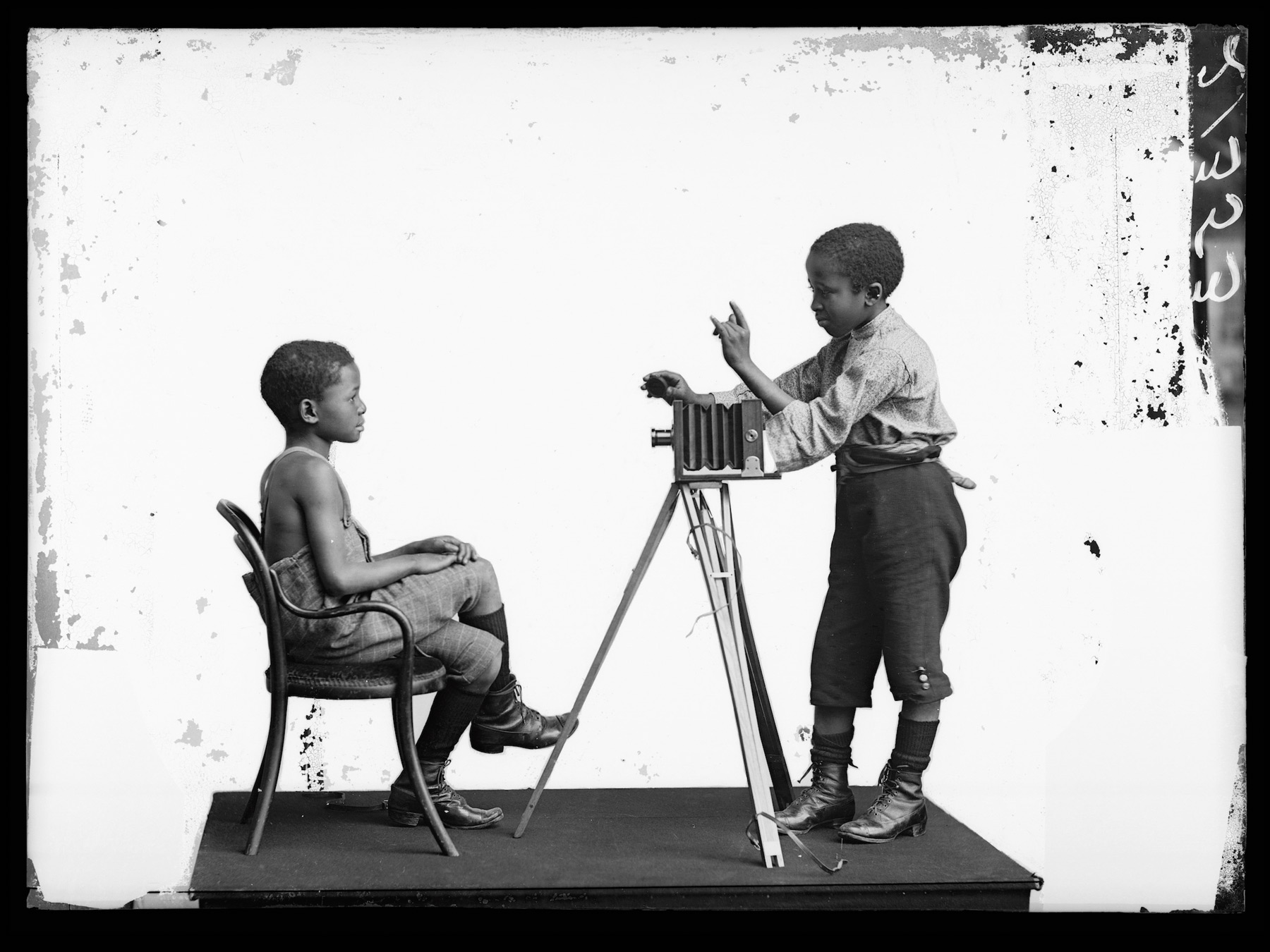

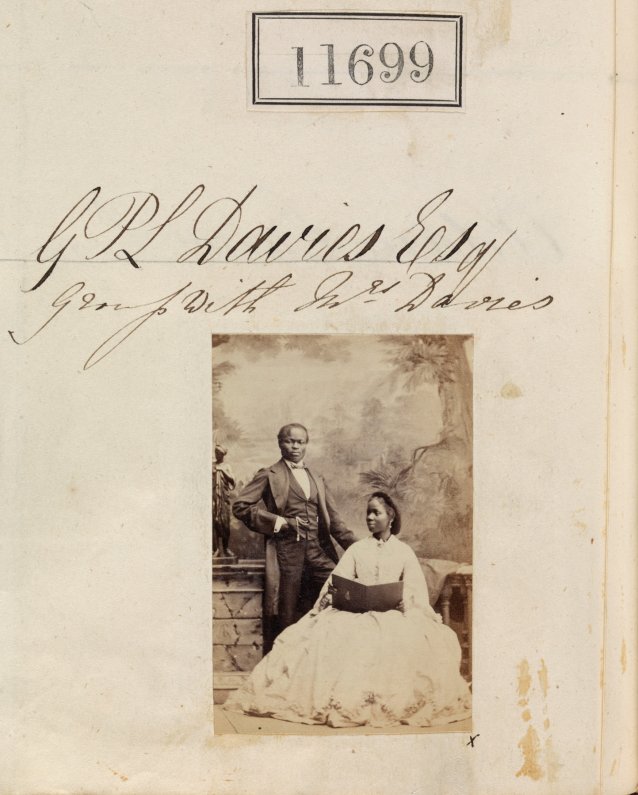

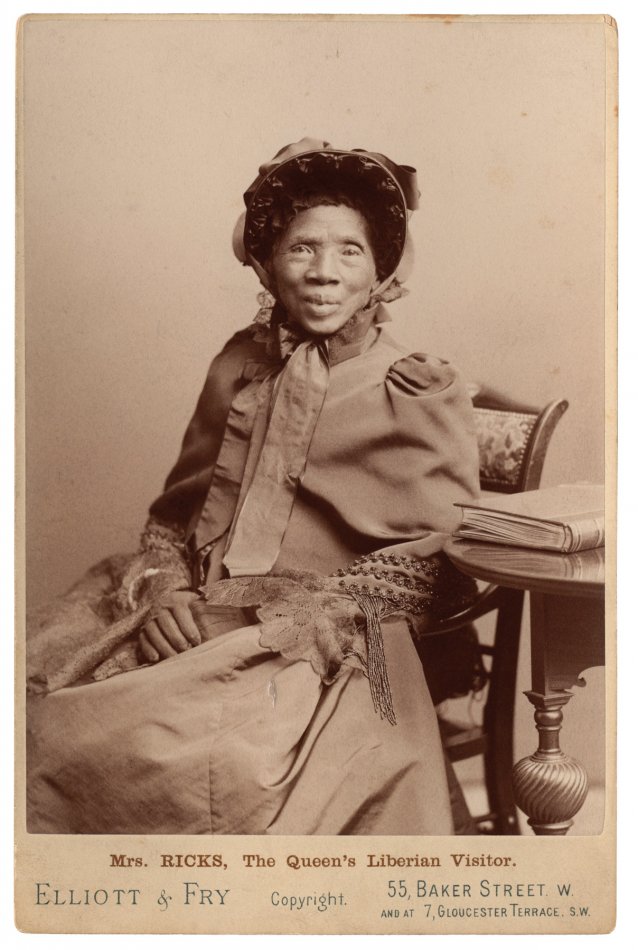

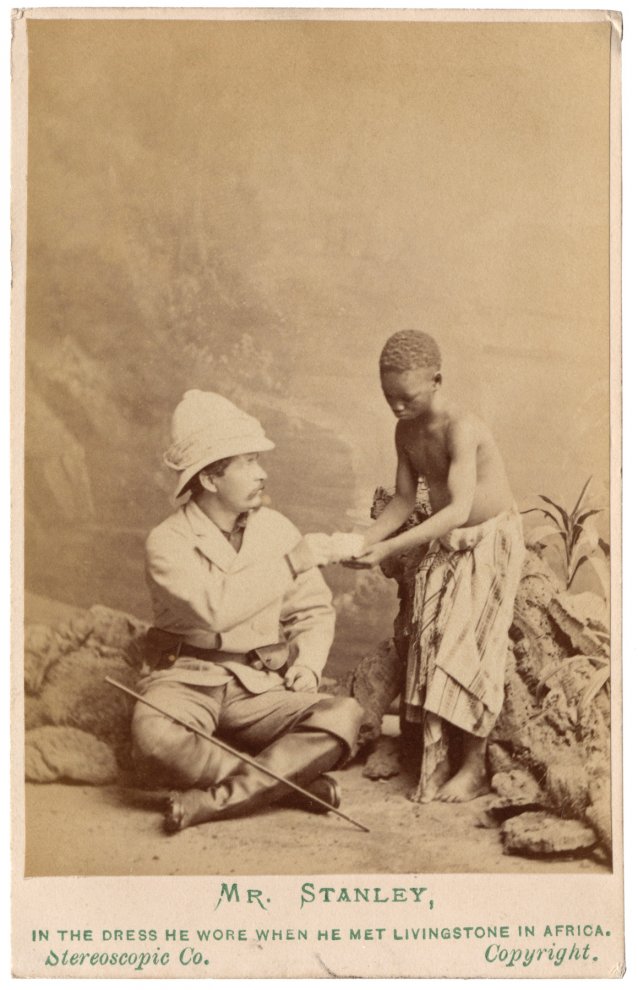

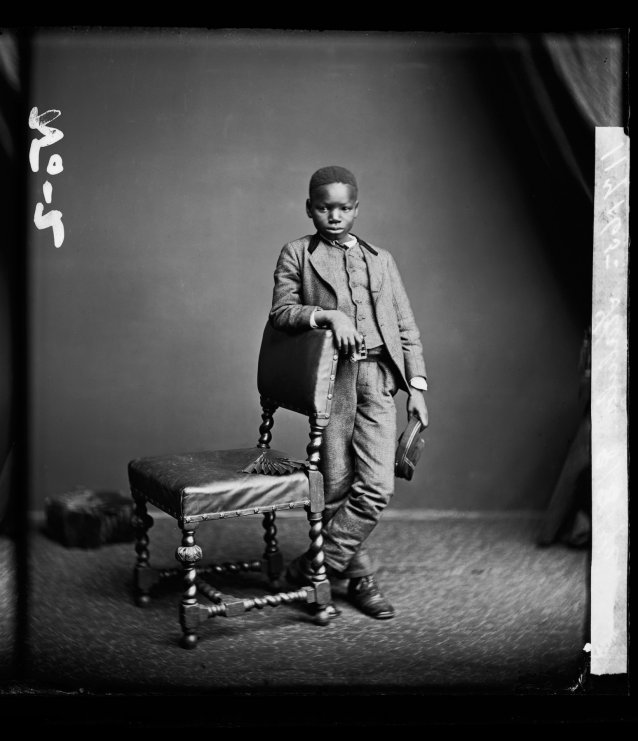

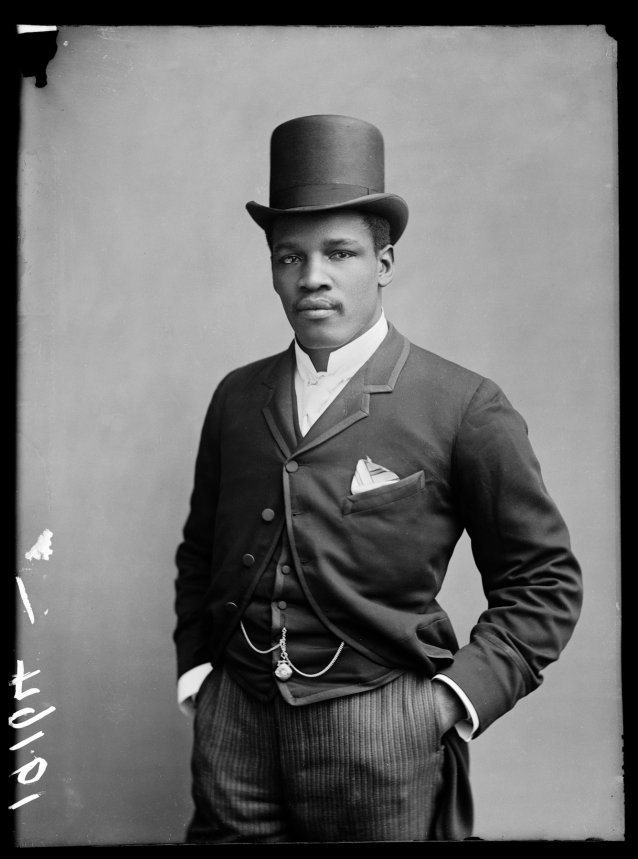

The exhibition Black Chronicles: Photographic Portraits 1862 – 1948 was a collaborative project between the National Portrait Gallery, London and Autograph ABP, a charity that works with photography and film to expand discussion of cultural identity, race, representation and human rights. The exhibition, which ran from May to December 2016, included forty original albumen cartes de visites and cabinet cards, together with nine large-scale modern prints from 19th century glass plates. The portraits included some of the earliest photographs of black and Asian sitters in the Gallery Collection; it also included material discovered in the Hulton Archive, a division of Getty Images, through a long-term Autograph ABP research project (supported by England’s Heritage Lottery Fund) investigating early representation of Black and Asian subjects in Britain.

I viewed the exhibition in late 2016 and was moved by the images, their accompanying stories, and the perpetual relevance of the themes explored. They demonstrate the strong presence of black lives and experiences within Britain, long before the major immigration from the Caribbean that began in 1948 with the arrival of the first large contingent of immigrants on the vessel Empire Windrush.

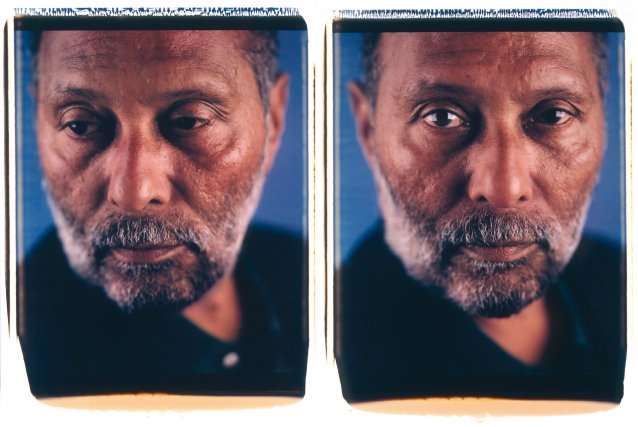

The exhibition layout was multifaceted; it consisting of the main space on the mezzanine floor at the front of the building, as well as display cases in two further Galleries. The final component was a single photographic portrait of the sociologist Stuart McPhail Hall, by Dawoud Bey.