The Portrait Gallery’s origin story speaks to the vigour and vitality that saw Edinburgh develop into a major cultural capital of Europe in the twentieth century. The honour of designing an extraordinary national building was awarded to Sir Robert Rowand Anderson (1834-1921), an architect well-known for some of Scotland’s major landmarks, and knighted for his contribution to the regal Balmoral Castle. In 1889, Anderson was ready to open the Gallery’s huge, heavy timber doors to the public. Passing under gargoyle-like sculptures and gazing at the building’s dour, dark red brick walls, visitors may well have felt a sense of awe bordering on foreboding.

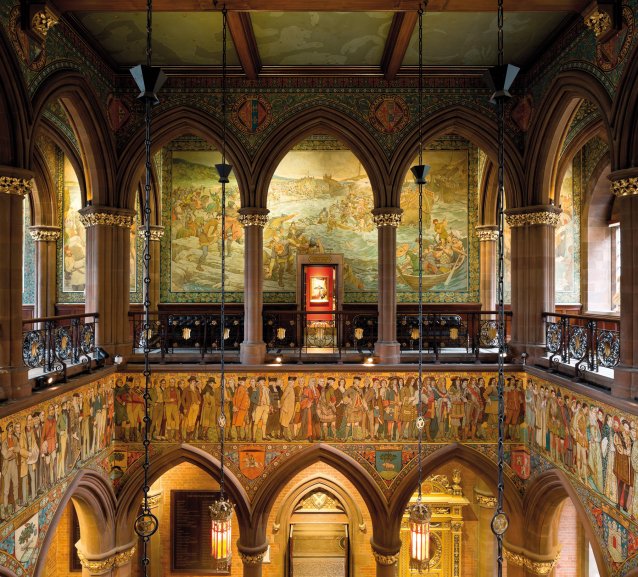

Perhaps the second-biggest moment in the Gallery’s history came in December 2011, when the building finally reopened after an extensive, eighteen month, £18 million renovation. Since then, the Gallery has sung with a modern clarity. After more than 120 years of benign neglect tempered by the odd bit of maintenance, the upgrade saw the restoration of architecturally purposeful delineation and natural light. In terms of museum practice, the Gallery can now employ present-day exhibition techniques and provide premium services for the visiting public, including a modern cafe, a functional entrance area, and efficient ‘wayfinding’. Today, the Gallery thrums with a rejuvenated, Edinburgh-esque, Neo-Gothic mojo.

Shortly after the building re-opened, BBC Special Correspondent, Scotsman Allan Little, captured the project’s achievement: ‘The striking thing about this gallery now is how connected it is to the living, breathing, developing life of this country. It is really connected. It is not a matter for history anymore; it is a matter of who we are now, and who we are going to become in the foreseeable and distant future.’

The stunning interiors, some of them revealed through the renovation, include William Hole’s (1846 –1917) wondrously ornate frieze, found in the Ambulatory (a delightfully old-fashioned noun!), its foyer/main hall. The processional frieze has a gold, gesso background and curlicues surrounding the parade of sombre, historic Scottish figures; they are standing formally, in the vein of a wedding party or meeting of world leaders, waiting to be photographed, captured for all time. Hole was born in England but his admiration of his adopted home of Scotland clearly dominates his major works. A member of the Royal Scottish Academy, Hole is also known for his book illustrations, particularly of various biblical themes.

A number of foundational figures loom large in the institution’s history. John Ritchie Findlay (1824-1898) can be described as the father of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, having provided funds for its building and endowment. A newspaper baron at the helm of The Scotsman, he gave a great deal of his wealth to the city of Edinburgh, bequeathing funds to improve medical facilities and providing assistance to impoverished children, historical research and social housing. From 1882, he began supporting the National Portrait Gallery, and his donation of more than £80,000 equates roughly to £120 million today ($200 million Australian dollars).