On Saturday night information was given at the Police Station, that four mounted and armed bushrangers were committing the most daring depredations on the St. Kilda and Brighton road. About five o’clock in the evening, Mr and Mrs Bawtree were stopped, bailed up, and robbed, and upwards of fifteen other persons were also stopped that evening by the same gang.

The above newspaper excerpt from The Argus describes a robbery by bushrangers in Melbourne in 1852. Up to twenty people were held captive for several hours before the offenders escaped with their loot. The English artist William Strutt (1825-1915), who was living in Melbourne, transcribed the article and in his unpublished autobiography described the incident as one of the ‘most daring robberies ever attempted in Victoria’. He also detailed other acts of ‘villainy’ committed in the colony, saying ‘it is clear there were elements of disorder which needed putting down with a strong hand’. Decades later in 1887, Strutt painted a large narrative work based on the incident, Bushrangers, Victoria, Australia 1852. The painting and its preparatory sketches record Strutt’s thoughts on what was at stake if these ‘elements’ remained unchecked, while also revealing his experimentation with characterisation and composition.

The preparatory sketches for Bushrangers demonstrate the systematic and thorough approach to building pictures that Strutt learnt from his training in Paris, where he attended the École des Beaux-Arts. The French Academy promoted a hierarchy of genres in which history painting – large, dramatic canvases of narrative scenes – were considered the highest form of art. Its house style at the time was the juste milieu (middle way), a conservative compromise between the restraint and rigour of Neoclassicism and the emotional charge of Romanticism. After seven years in the academic system, Strutt emerged as a superb draughtsman and renderer of the human figure, with an ability to compose complex narrative works in the classical style.

After a modest start to his career, Strutt decided to ‘plunge into the unknown’, and in 1849 set out for Australia. Strutt harboured ambitions to paint large history paintings on Australian subjects, but his main line of work was portraiture. His skills as a figure painter set him apart from his colonial contemporaries and he was arguably the most accomplished portraitist working in Australia at the time. He also actively participated in the Melbourne art world and, with other denizens of

the emerging scene, reformed the Victorian Society of Fine Arts in 1856. In 1862, Strutt returned to England and never came back to the Antipodes. He continued to paint Australian subjects, producing the large narrative works which have become his most famous paintings: Black Thursday, February 6th, 1851 (1864), The burial of Burke (1911) and Bushrangers.

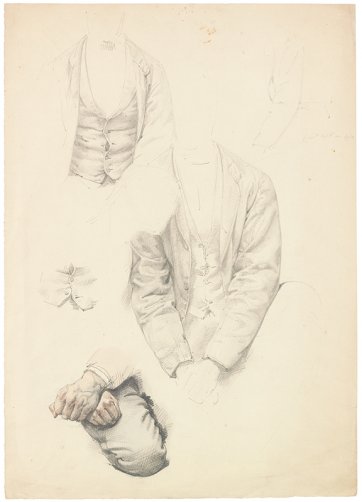

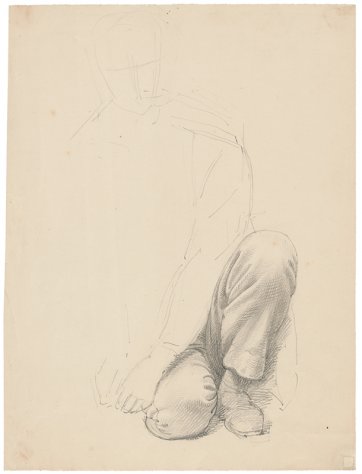

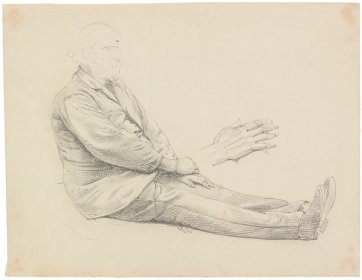

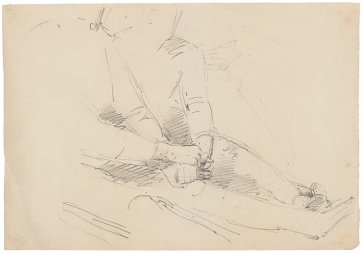

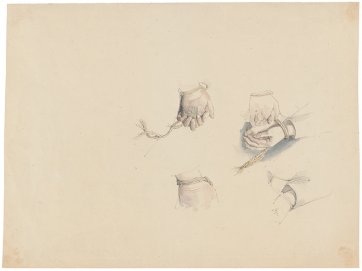

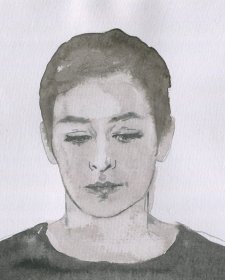

Strutt worked for six months on Bushrangers and his approach was methodical. He referred to his transcriptions of newspaper articles and costumes he had brought over from Australia, ‘the very ones worn by the colonists at the time’. The preparatory sketches provide valuable insight into how Strutt composed the picture. There are rapid outline sketches, which experiment with poses and compositional elements, and there are meticulous sketches of models and props where he obsessively perfects the clasp of a pair of hands or the crease in a pair of trousers. The sketches demonstrate Strutt’s talent for drawing the human figure and eye for detail. They also reveal how he experimented with narrative elements and characterisation, particularly with the central figures – the bushranger in the red shirt and Mrs Bawtree, the only woman in the painting. The other bushrangers are uncomplicated criminals, fixated on the cash, while the male victims are an inventory of colonial character types: the lawyer, the businessman, the vicar, the vagrant, the tradesman, the gambler. Mrs Bawtree is more than a type; she possibly represents, as art historian Chris McAuliffe has said, ‘the maiden Victoria … torn between the stability of good government and the perils of bad’.

The effectiveness of this reading depends in part on her proximity to the central villain, and the sketches show that Strutt played with the spatial relationship between these two figures and the characterisation of the bushranger. In one sketch, he separates them and has the bushranger point his rifle at the Bawtrees. In another, his face is slightly revealed as a handsome, mustachioed highwayman, a more attractive and seductive outlaw than his companions. However, in the final product Strutt pushed villain and victim closer together so the bushranger invades the space of Mrs Bawtree, and his face is now cast in shadow. Mrs Bawtree’s (and our) relationship with this figure is ambivalent and uncertain. It would appear at this point that the future of the young Victorian colony is in the balance. Which way will she go?

The painting and the preparatory sketches appeared in the exhibition Heroes and Villains: Strutt’s Australia which was displayed at the National Library in 2015 and will travel to the State Library of Victoria in July 2016.