In the days before Christmas 1828, a number of London newspapers published reviews of the spectacle then on offer from the panorama proprietor and painter, Robert Burford, at his premises on Leicester Square. ‘Mr Burford, whose pencil has so frequently delighted us with interesting excerpta from the regions of landscape’, and who ‘transports us to Nature’s choicest scenes whenever we wish to please our senses, or to satisfy our curiosity, has just produced a panoramic view of Sydney, the capital of New South Wales’, stated the Times on 20 December. ‘At first sight we were struck with the great beauty of the place’, it continued, and ‘if Mr Burford have not indulged his fancy in the execution of his present work, and heightened the beauty of the scene, one of the finest spots in the universe is appropriated, by a strange inconsistency, to the reception of the very dregs of society’.

Similarly, the Examiner wondered whether Burford’s delightful panorama might ‘cause such a yearning after a residence in that attractive spot, that a transportable offence would become as common as lying, and Hicks’s Hall and the Old Bailey be looked upon merely as rude passages leading to an earthly paradise’. The Morning Chronicle, meanwhile, enthused over Burford’s ‘genius, and his industry, for enabling us of the North to have a real idea of what exists among our brethren of the South’, while another paper declared that the panorama of Sydney ‘will add greatly to Mr Burford’s high and justly earned reputation’, and that it ‘surpasses in interest any we have yet seen’.

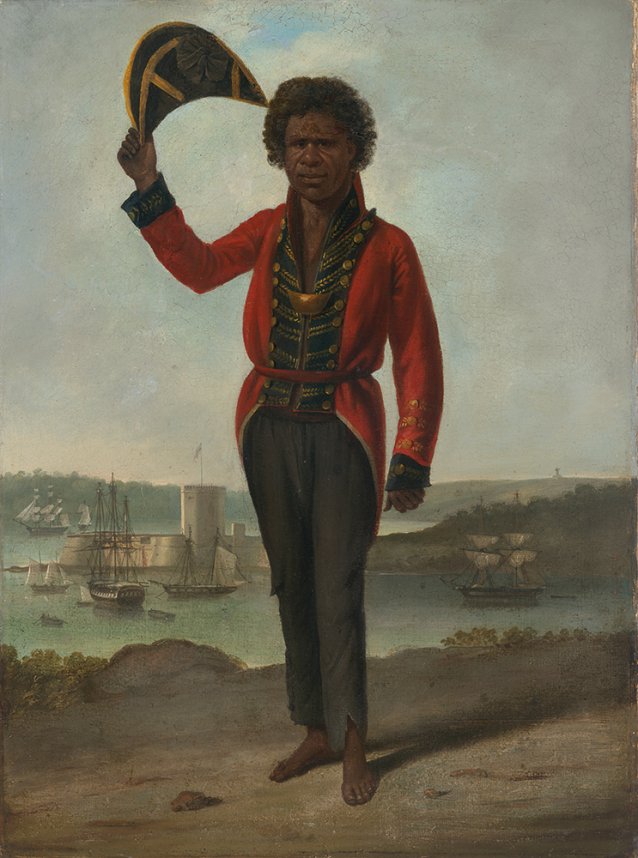

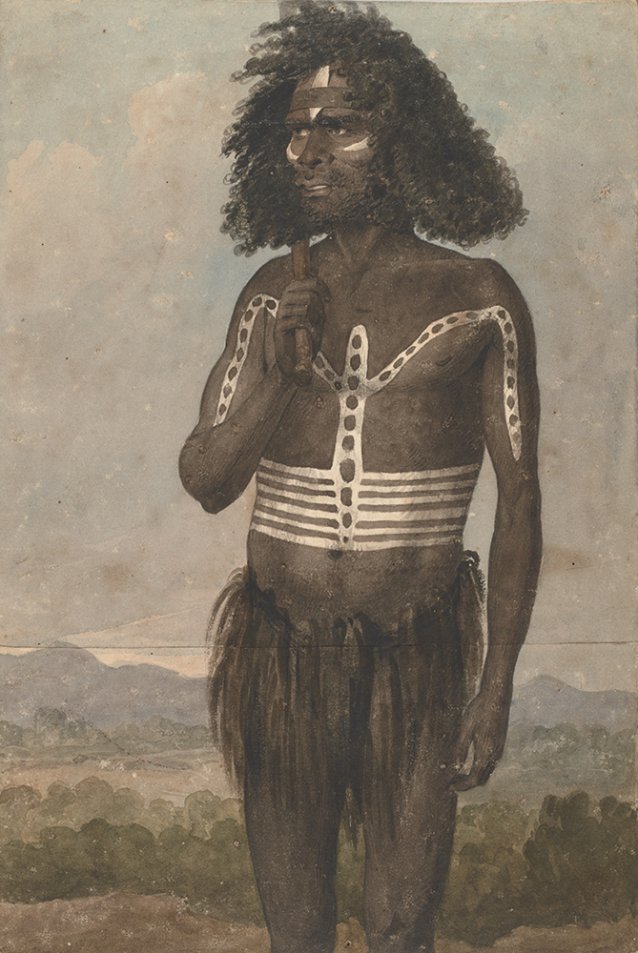

Presented in a purpose-built, three storey high circular building designed to the specifications of Henry Aston Barker, the inventor of the panorama, Burford’s view of Sydney had the added thrill of intense veracity, with viewers entering an immersive installation that created a disconcertingly ‘real’ encounter with the curious English outpost. The idea of a colony designed for the reception of those ‘whose residence in their native land was incompatible with the welfare of society’ had long been something that could intrigue, bemuse or repulse England’s exhibition-going classes, and by 1828 the appetite for news and evidence of the distant dominion and its people was such that it was ideal fodder for panorama painters such as Burford and other artists engaged on the boundary of popular culture and fine art. Indeed, the colonisation and consolidation of New South Wales coincided with the emergence of panoramas as a popular form of entertainment, or what the historian Richard Altick has since defined as ‘rational amusement’, whereby showmen or commercially-inclined artisans might turn the material culture of discovery, exploration and empire-building into a sensational yet educational attraction. In light of this, what is perhaps most interesting about this particular panorama was that it was produced by Burford from drawings made in Sydney in February 1827 by the intrepid and intriguing painter and traveller, Augustus Earle, whose work concurrently inhabited the spheres of art, information and entertainment. As art historian Jocelyn Hackforth-Jones and others have explained, Earle’s work was characterised by a winning combination of empiricism and reportage with Romantic, Picturesque and comic traditions. His travels, furthermore – in the Americas, the Pacific, Asia, the Mediterranean and various other places – were conducted for personal, opportunity-and-adventure-seeking reasons, leaving his documentation of the sights and peoples he came across unconstrained by the precise, record-keeping requirements of the state, or the predilections and instructions of a wealthy patron.

The London-born son of an American painter, Augustus Earle (1793–1838) ended up in Australia by accident in January 1825. Earle had spent much of the preceding year stranded on Tristan da Cunha, a remote volcanic island in the south Atlantic with an adult population of eight, his ordeal coming about at the end of a four year period during which he had travelled and worked in New York, Philadelphia, Brazil, Chile and Peru. Against advice, Earle boarded a ship called the Duke of Gloucester in Rio de Janeiro in February 1824, thinking it would eventually get him to Calcutta. When the vessel anchored off Tristan da Cunha, Earle seized the chance to explore the island, going ashore with his dog and a shipmate only to be left behind when the Duke of Gloucester inexplicably sailed without them.

‘Thus I suddenly found myself placed in a situation the most singular and distressing’, Earle wrote in a letter published in the Hobart Town Gazette in February 1825. ‘Eight dreary months did I endure on this dismal and sequestered spot, in a state of anxiety and expectation indescribable.’ During this period, Earle fulfilled the role of chaplain and of tutor to the children of the island’s pipe-smoking ‘governor’, and, given his ‘most vexatious and miserable’ situation, sought also to keep himself sane by venturing around the hitherto un-depicted island, producing a number of landscape views and representations of daily life before his art materials ran out. His output included a self-portrait titled Solitude, watching the horizon at sunset, in the hopes of seeing a vessel, Tristan d’Acunha, showing Earle and his dog, Jemmy, looking dejectedly out to sea, and we see him again in Governor Glass and companions, Tristan d’Acunha, an interior scene recording the exceedingly limited society he quitted with relief when the Admiral Cockburn, blessedly en route to Van Diemen’s Land, called at the island and ‘released me from my melancholy confinement’.