The view of the Manhattan skyline from the Newark Airport bus sets off prickly, hot shivers in me. It’s summer. Still before nine in the morning, and the peep shows and adult shops twinkle along West 42nd Street from the Port Authority Bus Terminal to Times Square. The strip is hot with solicitation and I am feigning indifference. It’s 1989. I’m twenty-two and on my own in New York City for the first time. Hispanic boys my age and younger are hanging out at the bus terminal exits and along this strip – hustlers with regular clients.

‘Like brothers,’ says Robert McNamara in his 1994 book, The Times Square hustler: Male prostitution in New York City, ‘hustlers usually pair off and hang out together’. They become buddies, one waiting outside a hotel while his friend is inside with a client. The boys share their earnings. Most of the boys see their hustling as an income-producing job. Most identify as heterosexual and commute to and from Manhattan like the older men who are their clients. A twenty-one year old hustler tells McNamara ‘clients want a young, skinny looking Puerto Rican, not a white boy’. Some of the older boys are supporting wives and kids.

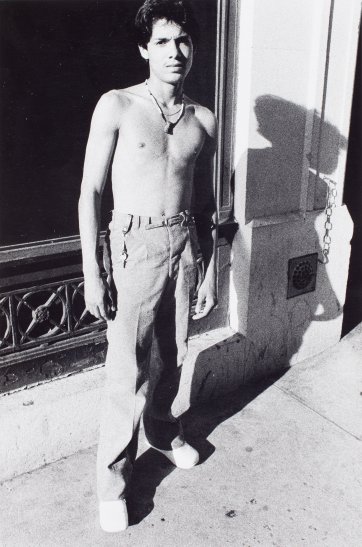

Thirty-five years ago, Larry Clark photographed Hispanic boy hustlers along this strip. His photographs are candid and observational. The depth-of-field is naturalistic, the tonal range is uniform and soft, the gelatin-silver prints are silky. In these visual rhythms he reveals a tender attitude. Clark has great empathy for the boys he photographs. He lets us glimpse the emotional need behind their bravado. His pictures can be heartbreaking in their honesty.

Writing about these images for Flash Art magazine in 1981, Lynn Zelevansky responded to Clark’s technique, to his subjects, and to his approach. ‘His hand is unusually steady and he knows and renders well the graphic and emotional qualities of the available light.’ Zelevansky saw Clark’s portraits as ‘sympathetic ones of sometimes beautiful, sensitive looking boys who are locked into a no-win situation’. The photographs ‘don’t make judgements, they simply give evidence’.

The tensions of young manhood fascinate Clark. His black-and-white documentary images of young outsiders reveal raw feelings. He has always photographed young people, and when he is photographing boys he looks at them with deep curiosity. In 1962 he started taking pictures of girls and boys – mostly boys – on the fringes of the oil-town, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Clark was barely out of his teens. With his Leica rangefinder, young Larry calmly described the intense and loose behaviour around him. His amphetamine-stimulated company had already embraced him, and his photographing of them was naturally accepted.

‘I was just part of the scene,’ he told Raphael Cuir in 2007, ‘and it was very organic, it really came from a place where there was no thought ever to show the pictures or publish the pictures or anything for a while.’ In 1971 Clark’s self-published book of photographs, Tulsa, offered up its bruised youth utterly openly. The softly handsome and neatly-dressed kid fresh out of photography school had found beauty in the faces of his exposed comrades.

After Tulsa, his photographs of hustlers were discussed in art magazines and in the Village Voice. Zelevansky wondered about Clark’s motivations for photographing these boys, since he had grown older and moved away from his Tulsa milieu, but Clark’s authenticity won her over. His work had integrity, she said; it was like investigative journalism. Zelevansky saw that the boys he photographed ‘appear to have the option of rejecting him’.

I was in New York City again in 2005. A survey exhibition of his work was on show at the International Center of Photography. At the Museum of Modern Art research library, I spent hours looking through Clark’s artist files. The research was the basis for a doctoral thesis on the portrayal of adolescent boyhood in art, and his work was central to this theme.

‘No earthly object is so attractive as a well-built, growing boy’, wrote American youth educator Henry William Gibson in 1916. The downy hair of an adolescent boy’s cheek was often the subject of historical Persian and Roman poetry. Clark sees this beauty too – and its defeat. He says his work ‘has to do with the loss of innocence, innocence lost and what happens’. Clark’s images of adolescent boys are poignant. He perceives the lingering spirit of the boy in the growing body of the young man. In 1980 and 1981 the National Gallery of Australia acquired over eighty of his photographs – the most significant collection of Clark’s work in Australia.

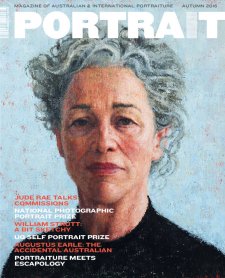

A selection of these pictures is to be included in the National Portrait Gallery’s forthcoming exhibition, Tough and tender. The exhibition presents the work of seven Australian and American artists whose photographic work reflects on vulnerability in manhood. Clark’s gentle and raw exploration of male identity rests at its heart.