We spend our lives reading faces – those of strangers, intimates and everything in between. The pleasure we take in the painted portrait is (as it is with all painting) that of re-tracing our perceptions, but portraiture offers something else. Call it what you will: an inbuilt voyeurism, an opportunity to scrutinise; whatever it is, portraits do not function in quite the same way as other kinds of paintings. The drama of likeness, characterisation and narrative tends to override the formal elements that normally structure a work. In some ways, portraiture has more in common with theatre (at the extreme, caricature meets vaudeville). Perhaps this is the reason for its endurance, long after its purely documentary function has been lost to photography. The popularity of the Archibald Prize, which never fails to draw huge crowds, also hints at an inherent democracy in the portrait. Everyone can read a face; everyone can have an opinion. Social status, notoriety, the glitterati – portraits are the original pin-ups, the genre tailor-made for celebrity culture.

A commissioned portrait is one where an artist is contracted to paint (or, less frequently, sculpt) the likeness of an individual or group, usually for the purposes of commemoration. This can be a private affair, such as a family commission, but more often it is an institution or corporate body that does the contracting. The practice is steeped in history from its beginnings in the courts of Europe, and is thus strongly associated with the mechanisms of social status, power and wealth. In commissioning a work, the client usually requires certain conditions which necessarily limit the artist. This tends to contribute to the idea that the commissioned portrait is creatively constrained and that the portraitist is, at best, a kind of spin doctor hired to present a laundered or enhanced version of the subject, or a mercenary enlisted to enforce the social status of both subject and commissioning body for generations to come. At worst, portrait commissions might be considered the realm of the hack and the social climber. From a popular point of view, the very thought of constraints runs counter to notions of creativity and artistic insight, but this is a relatively recent idea. Limits can present extraordinarily exciting creative challenges – ask any architect.

Acute characterisations are also assumed to be the result of intimacy, rather than a commercial exchange between an artist and a previously unknown subject. The commissioned portrait tends to register as diminished in comparison to its more familiar counterparts, which are presumed to robustly reflect the ‘honesty’ of close personal relationships. The fact is, however, that many of the most acutely observed portraits in the great collections are the result of commercial transactions, and depict individuals who were not intimate with the artist. This is the paradox: even the most intimate portrait requires at least as much dispassionate analysis as impassioned participation. In the same spirit as novelists who, often much to the dismay of intimates, mine personal relationships for their work, many of the great painters have cast a ‘cool eye’ over their subjects – intimate and otherwise. Intimacy might even confuse or compromise an artist’s work, as was the case with Francis Bacon, who preferred painting portraits of his friends from photographs, claiming that it protected them from the violence of his project.

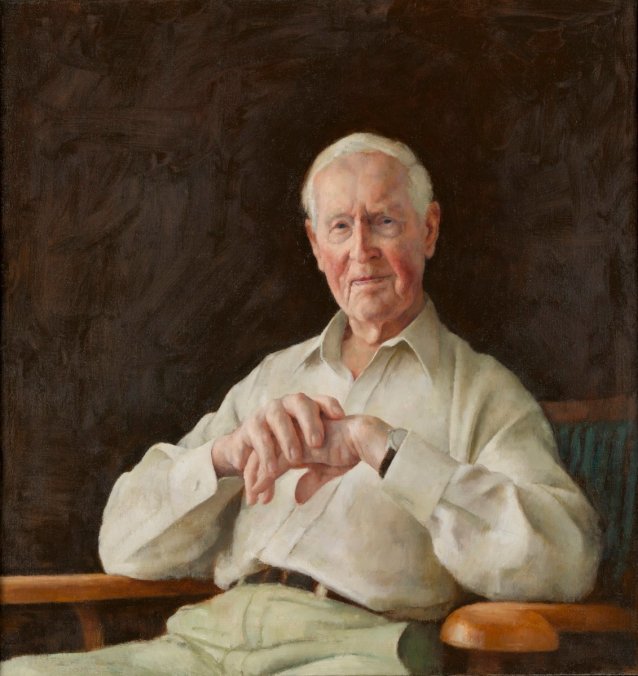

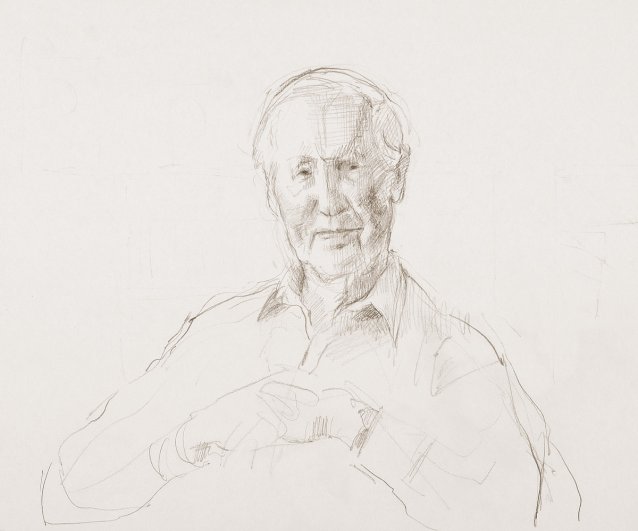

So while the practice of painting portraits on commission continues, and indeed sustains many individual artists, attitudes such as these seem relatively unexamined in either popular or even critical commentary. I suppose the field of contemporary art practice is so broad now that portraiture, and more particularly portrait commissions, occupy only a very small, albeit stubbornly enduring corner. Although portraits comprise only a fraction of my studio preoccupations, a portrait commission can both augment my living and present an enduring challenge. My first commission was in the mid 1980s when Robyn Brady, then director of Painters Gallery, was approached by the family of Justice John Lockhart. I had a studio in Ultimo, and Justice Lockhart would walk from the High Court buildings across the Pyrmont Bridge to sit for me during his lunch hour. He was a very good-natured man, which was just as well, as I was nervous. I can’t remember how many sittings we had, but looking back it all seems so leisurely. John certainly had no mobile phone pinging emails! Nevertheless, I did take photographs that, in the end, I felt I had relied on too much. It took years to understand what photography had to offer a portrait painter.