In the freezing cold winter of 1926, an Australian adventurer arrived in Kabul seeking an audience with Amanullah Khan, the Emir of Afghanistan. He called himself ‘Murray the Escape King’ and he was fulfilling a dream he had harboured since childhood – to travel the world as a magician. Aged just twenty-five, Murray had already been to Peking where he was manacled hand and foot to a railway track as the Shanghai Express bore down on him. In Phnom Penh, the King of Cambodia enjoyed his sleight of hand so much he offered him one of his thirty wives as a reward. Murray politely refused. On Christmas day in 1925, hundreds gathered at the Gateway of India in Bombay to watch him being thrown into the murky waters of the Arabian Sea in a mailbag, while handcuffed and in leg irons. But the challenge Amanullah Khan now set would have given Harry Houdini, Murray’s idol, second thoughts. The Emir showed him the most secure prison cell in his kingdom – a cell so claustrophobic it made the Black Hole of Calcutta ‘look like a Swiss chalet’, Murray would later recall. If he could escape, he could keep the bag of 5000 silver rupees the Emir had left inside. If he failed, he would remain in the cell for the rest of his life. Without hesitating, Murray took up the challenge and won.

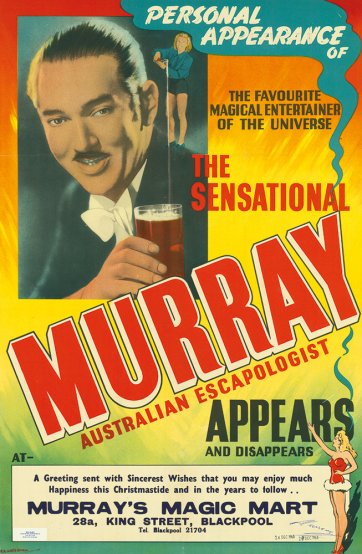

Nicknamed the ‘loveable rogue’ by his followers, Murray, whose real name was Murray Carrington Walters, would later boast of taking to the stage ‘in every quarter of the globe, from Alaska to Abyssinia … and from Afghanistan to the Steppes of Tartary’. When World War Two broke out he was performing at Berlin’s Wintergarten before Hermann Goering and Adolf Hitler, who as a young boy harboured his own fantasy of becoming an escape artist. In total, the ever debonair-looking Murray toured eighty-seven countries, becoming the most travelled entertainer of his day.

Murray’s exotic exploits seem remarkable, even in today’s globalised world of popular entertainment. In fact he was treading a well-worn path established by generations of Australian magicians, actors, musicians and circus performers since the 1860s. Backed by a brash class of showbiz entrepreneurs, Australian entertainers cornered the Asian market, bringing everything from Shakespeare to bush ballads to the stages of Shanghai, Rangoon, Colombo and dozens of other metropolises. Companies of Australian minstrels played in the hill stations of the Himalayas and in the courts of Indian Maharajas. Illusionists studied the secrets of Chinese street magicians in Nanking and Shanghai. Circus performers set up their big tops in the jungles of Java and scoured the animal markets of Burma and Bengal for tigers and elephants to train for their shows.

Australia was uniquely placed to take advantage of the insatiable demand of audiences in Asia for Western popular culture. The development of regular steamship services in the 1870s opened up new entertainment circuits that ran from the west coast of North America to the ports of the eastern Pacific, and from Australia to England via South East Asia and the Indian subcontinent. Australia became both the final destination and the starting point for generations of entertainers chasing fame and fortune in lands they often knew very little about. Some shared their stories with biographers; others kept scrapbooks of now yellowing playbills and newspaper reviews, but the most vibrant record of those times are the studio portraits and press photographs preserved in collections such as those of stage magicians Will Alma in the State Library of Victoria and R.B. Robbins in the Mitchell Library in Sydney.

In many ways, Murray epitomised this vibrant class of entrepreneurial entertainer. Born in Melbourne in 1901, he mastered the art of escapology as a young boy after buying a pair of ‘regulation wrist irons’ from a mail order firm. To practise his routine he would chain himself to his bed at night and then throw away the key. By the time he had turned sixteen, Murray had left school and found a job as a butcher’s assistant on the ocean liner Niagara, bound for Vancouver. After a series of unsuccessful attempts at cracking the vaudeville circuit in the United States, he set sail for Singapore, working for his passage as a ship’s boy. At night when his boat was docked in the harbour, he would secretly slip out and change out of his white ducks into a smart suit and entertain guests at Raffles Hotel with sleight-of-hand. From Singapore he sailed to Bombay, where he saw fakirs performing magic in the local market, before touching ports in the Persian Gulf, South Africa and South America. Disembarking in Buenos Aires, he met the celebrated Belgian magician Servais Le Roy and became his assistant for several months.

When he finally returned to Australia in 1923, Murray’s ambition was to earn enough money to go back to Asia. After spending Christmas of that year with his mother in Java, he took to the road performing before Asian potentates, gin-pickled expatriates and crowds of eager locals. In Calcutta he dived off the Howrah Bridge manacled in a straight-jacket, six pairs of leg irons and twelve feet of chains. By 1926 he was commanding £80 a week in Penang, with The Times of London declaring him to be ‘greater than Houdini’. In London he created a sensation by escaping from a straight-jacket while suspended from a crane, upside down, fifty metres above Piccadilly Circus. When he tried to repeat the act in Sydney’s Shakespeare Place in February 1928 he was arrested. At a court hearing a few weeks later, the judge ordered him to pay a fine of five pounds or spend a month in Long Bay prison. Murray replied that he would prefer prison ‘if they can keep me there’, but later changed his mind, fearing that if he escaped he would be rearrested, thereby jeopardising his performance schedule.

Murray was not the only Australian illusionist drawn to Asia. In 1933, Les Cole, better known as ‘The Great Levante’ and widely regarded as Australia’s greatest magician, mimicked Murray’s feat of jumping off the pier at the Gateway of India, bound in handcuffs, as a large group of expats wearing solar topees and a somewhat smaller crowd of bemused locals looked on. In 1927, together with his wife Gladys and their six-year old daughter Esmé, Levante began a tour of Asia and Europe that would last thirteen years. The tour included eighteen months in pre-independence India, where Esmé was billed as ‘the Daughter of the Gods, the Child Phenomena, Mentalist and Crystal Gazer’. Their travels nearly ended in tragedy when the car Levante was travelling in hit several men walking along the road at night near Peshawar in present day Pakistan. The men were Muslims and one was badly injured. When the crowd that gathered saw that Levante’s driver was Hindu, they started attacking him. Fortunately Levante had his ‘Sword Box Illusion’ strapped to the back of the car. Wielding a sabre and with his wife behind the wheel, he beat off the attackers while standing on the running board. They eventually delivered the injured man to the nearest hospital in Kohat.

Murray and Levante belonged to a long tradition of risk-taking magicians who travelled the world searching for new audiences, keeping ahead of their competitors by learning new tricks. Their success owed much to the hard work of pioneering entertainers who had gone before them. Back in October 1860, advertisements had begun appearing in newspapers in Calcutta for ‘Lewis’s Great Australian Hippodrome and Mammoth Amphitheatre on the Maidan … just arrived from China’. The cast included ‘Lilliputian Tom’, JM Wolfe ‘the celebrated Shakespearean Jester’, and Austin Shangahae [sic], who was billed as the ‘Chinese Tom Thumb’. The Hippodrome was the brainchild of entrepreneur and circus performer George Lewis. Born near Drury Lane in London in 1818, Lewis arrived in Australia in 1853, then started a circus and toured the goldfields.

After marrying Rose Edouin in 1864, the pair formed a theatrical company that commuted between Australia, India and China for nearly two decades, bringing the plays of Shakespeare and melodramas such as School for Scandal.

According to Melbourne-based historian and Lewis’s biographer Mimi Colligan, countries such as India represented a vast untapped market for all manner of entertainers. ‘You had the public servants who remembered what was happening back in England and wanted more of that kind of entertainment. Then you had the local people who were interested in the shows but could also be quite scathing of the performances.’ It was a lucrative combination. The 1873-74 season, which The Era’s Calcutta correspondent described as the ‘weakest yet’, still netted Lewis and Edouin a profit of £80,000.

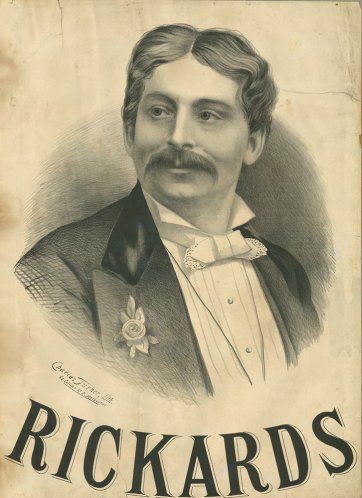

The money to be made from sending entertainers into Asia was not lost on men such as Robert Sparrow Smythe and Harry Rickards. London-born Smythe arrived in Australia in the early 1850s as part of the great wave of migration that accompanied the gold rushes. After working as a journalist, he turned to theatrical management and toured through South East Asia, India and South Africa, scouting for opportunities. He became the first manager to take a company into Japan after the 1854 port treaty, and, as his 1917 obituary noted, ‘the first to prove the possibilities for professionals of the hill stations of the Himalayas’. His crowning achievement was organising Mark Twain’s round-the-world lecture tour in 1895.

Now remembered as the king of Australian vaudeville, Rickards started his career as a music hall singer in England. In 1871 he made his debut at the Princess Theatre in Melbourne, wearing a top hat, twirling a cane and sporting a drooping, silky moustache he twisted into corkscrews on the stage. He returned to Australia in 1885 and 1888, before settling permanently in 1892. A year later he opened his first theatre in Sydney, the Tivoli. By the early 1900s he had a string of venues in Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth, which he developed into one of the most important vaudeville circuits in the world. Artists and entertainers typically spent twelve to sixteen weeks on the Tivoli Circuit in Australia before playing for six weeks on one of his affiliated circuits in India or South Africa. In addition to his ever-popular minstrel troupes, Rickards is credited with introducing Australian audiences to some of the world’s greatest performers, including the illusionist Carl Hertz (who screened the first motion pictures in Australia on 22 August 1896), the young WC Fields, the strongman Sandow and the renowned juggler, Paul Cinquevalli. In 1910, Rickards arranged for Houdini to make the first heavier-than-air flight in Australia; it took place at Diggers Rest, near Melbourne, in a Voisin biplane.

Murray was still a child conjurer when Rickards died in 1911, but when JC Williamson added the Tivoli Circuit to his theatrical empire in the 1920s he made a point of featuring the now famous escapologist in his shows. A March 1928 review in The Sydney Morning Herald described Murray’s baffling performance as having ‘all the magic of the Arabian Nights’. In 1947 he was back on the Tivoli Circuit, this time promising to jump handcuffed and in chains off the Sydney Harbour Bridge – a feat he never attempted. Murray’s career ground to an end in 1953 when he was diagnosed with an unspecified ‘nervous disorder’. He retired to Blackpool in England where he ran a magic shop, but never quite gave up the hope of returning to the stage. ‘I want to hear again the applause of the people in many strange lands,’ he reminisced to his biographer Val Andrews in the early 1970s. ‘I want to see again the wonders of the world. I want to feel that wonderful feeling of freedom attained by the freelance traveller who can always earn his keep.’