In the middle of 2013, Nicholas Harding was in Paris on an Australia Council Cité des Arts Internationale residency. It was spring, and he set about painting the city’s commuters, dogs, ducks and flowers. But one day, a flimsy replica of the Globe Theatre popped up outside his apartment on the rue de l’Hôtel de Ville. Watching the actors dressed in costume, waiting for their entrance cues, moving around outside his windows, pacing, practising their lines and dragging on cigarettes, Harding filled a small sketchbook with his observations of them.

In Sydney, Harding’s friend Hugo Weaving saw some of his drawings of actors on Instagram. Scheduled to play Vladimir in the Sydney Theatre Company’s production of Waiting for Godot in late 2013, he invited Harding (an habitué of the theatre) to come and watch some rehearsals. Harding began drawing from the moment the actors were up on their feet in rehearsal, and he sketched in a fever through five public performances of the play, three of them from the wings. When his sight line was obscured, he drew from photographs, but he made himself maintain a lively pace and dextrous rhythm.

Now, as he looks at the work he made over his months with the company, Harding traces his accommodation to what he observed: ‘Initial awkward tentativeness as the concepts and motivations were grappled with, eureka! moments followed by consolidation and more inquiry; faith in process as insights into the text and its characters began to bring the play’s reality into being. I began to trust my presence in this theatrical parallel universe, where “play” comprised rigorous attendance to imagination, talent, sheer hard work and Beckett’s stage directions. And then all turned back into “play” again. And this wasn’t a steady, ascending gradient of understanding. Some days brought setbacks and doubt. Once rehearsals were done and the time came for performing on stage and drawing from the wings, the actors were in command of the text and their stage craft, and I was more adept at the observational drawing that the pace of the action required.’

Harding had not only to become familiar with the routines of rehearsal, and the actors’ adoption of character, but to learn to control the speed of his drawing to achieve acuity with line; to judge how much to draw while looking at the action or at the page; to cope with working on a rough and ‘thirsty’ paper with an Indian ink-filled cartridge chisel-nose felt-tipped pen. ‘I was unaccustomed to the coarser paper and it became a metaphor for the actors’ dealing with the play’s resistance to a conventional understanding of narrative,’ he recalls.

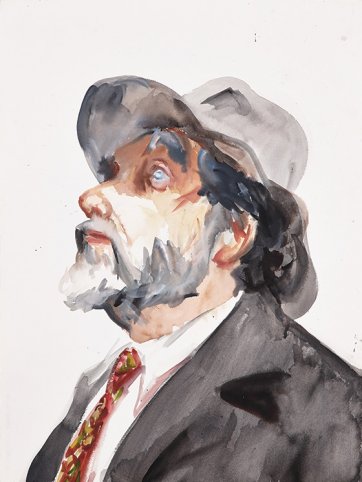

In the cotton-fibre sketchbooks there are scores of drawings of hats. Boots. Suitcases. Collapsible tables and chairs. Coats too big. Trousers too short. One drawing reveals a lot about the rest: it’s of Richard Roxburgh in profile, with his arms folded. Though he’s in costume - in Gogo’s hat at least - his attitude tells us that he’s not in character. He’s watching his colleagues; he may well be waiting for something, but he’s definitely not waiting for Godot. When Harding’s drawing the actors in character, you can tell from a wildness or a vacancy about the eyes; there’s an excessive uprightness here, a touch too much slack in the body there. There’s Weaving as Didi sitting on the floor, angled like a bookend, beard raised, fingers scrabbling at his pants, boots pointing skyward, while Quast as Pozzo bends forward on a minute stool, knees splayed, the lines of his hat concentric, those of his shoulders and arms undulating like striations on an oyster shell. There’s a much sparer rendering of Mullins as a classic Christ-figure, long face downcast and shadowed. There’s a spread where Harding and Roxburgh are lightly rendered figures on the periphery - Weaving, hands on hips, inquisitive, Roxburgh identifiable only by his stance, his hands soft claws - while in the ditch of the paper, Quast, a black colossus, drags at the stricken figure of Mullins, arms outflung, thin legs trailing.

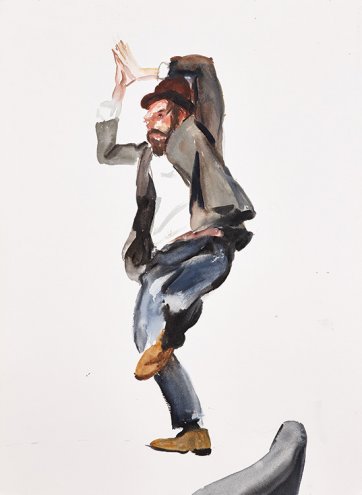

As his project ripened, Harding turned to other mediums: gouache, and, eventually, oils. By the end of 2013, the faces of his actor friends were extracted and developed from the sketchbooks to loom in colour from his studio walls. I saw Weaving looking kinaesthetically alert to something that you could tell wasn’t there; Mullins twisting to look over the back of a chair with an expression of moronic malevolence. Roxburgh’s gaze roved over all and nothing at once; his piggybacking grasp on Mullins was desperately vicious. Quast, though barely more than a pile of clothes, was still a man, crouching in a rictus of agon. In two alarming and pathetic gouaches, Roxburgh and Weaving were dancing, clumping around. It was all frantic and enervated at once; but the gouaches themselves were elegant: spare and refined.

Harding was introduced to Beckett’s work as a schoolboy; but it wasn’t until he was middle-aged, concentrating intently and working in an ambitious, demanding new way that he could encompass Godot’s brilliant balance of violence, humour, despair and grace. The drawings attest to Harding’s hunger to learn: at the broadest level, across centuries, about the great expressions of Western drama and art; and at the narrowest, about himself, his own corpus and history, the buried and accreted influences on his work. He writes: ‘Beckett’s contemplation of our existential folly acknowledges both the cruelty and tenderness in our relationships with each other. He recognizes both our frustration and stoicism as we endure the absurd conundrum of our very being. Pozzo cries in Act 2: “Have you not done tormenting me with your accursed time! It's abominable! When! When! One day, is that not enough for you, one day he went dumb, one day I went blind, one day we'll go deaf, one day we were born, one day we shall die, the same day, the same second, is that not enough for you? (Calmer.) They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it's night once more.”’

Although he draws instinctually, wherever he goes - on the street, on the train, at the table - the artist also relishes intellectual and imaginative exchange with disparate art forms and artists, living and dead. The artist’s ‘dialogue’ with others might materialise as allusion; or remain subconscious, at least for a time. Harding’s project was all his own; but it was veined through by images, influences and techniques of a line of artists from Goya to Daumier, to Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec, through Sickert’s Camden Town Group to Bacon and the figurative painters of the so-called School of London, especially Leon Kossoff. In retrospect, Harding acknowledges the influence of Toulouse-Lautrec’s theatre and cabaret drawings and paintings on his Godot series. Then again, for years, he’s been fascinated by the themes and techniques of Goya – especially the Caprichos series. There’s a drawing of Goya’s in a book he has that shows a man tumbling downstairs; and he was reminded of it as he watched Luke Mullins practising falling, rolling over Lucky’s suitcases again and again. Moreover, in the sketchbooks there are two drawings of Mullins, writhing lumpily, that are redolent of figures by Francis Bacon. In fact, though the Beckett Estate demands strict adherence to Beckett’s production notes, and Andrew Upton worked within the playwright’s prescription, he was inspired, too, not only by the partnership of Laurel and Hardy and the clowning of Buster Keaton, but the painted figures of Bacon. To help inform Luke Mullins’s interpretation of Lucky’s ‘dance’, Upton placed images of Bacon’s contorted figurative forms on the floor; starting from there, Mullins retained the spirit of these fleshy figurations as his dance took on a life of its own. Harding comments that it was a fitting reference, ‘as Bacon’s warping bestial forms were a response to post-war Europe as much as Waiting for Godot was Beckett’s rumination on the European wasteland of the mid-twentieth century.’

Slaking the thirst of his paper in the theatre, Harding finished on a high note: ‘It usually took about two rehearsals and two sessions from the wings to fill a sketchbook. But having become familiar with the performance’s tempo by the time of the last “from the wing” sessions, I worked very quickly and completed a sketchbook during one night’s performance. It seemed a fitting adieu! for my experience with the production’.

It would be thrilling to see Beckett leaf through that sketchbook; to see him pace catlike around a gallery of Godot gouaches. I imagine him nodding, slowly, his bright eyes narrowed and the corners of his thin lips upturned.