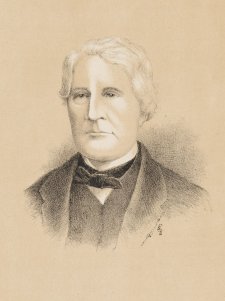

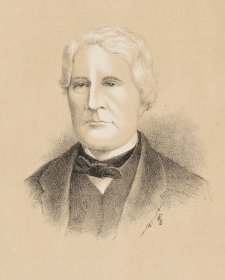

Despite its matter-of-fact subject of a professional at the drawing board, Lina Bryans’s portrait of Alex Jelinek inscribes a grand passion: it was painted at the outset of an affair that lasted the rest of their lives. The two unconventional 'creatives' started a relationship that was unorthodox: the 30 year-old Jelinek had been introduced to Lina - at 46 half his age again - by her son, the journalist Edward Bryans. Lina, the glamorous bohemian divorcée with old Hallenstein money, had been a central figure in Melbourne culture from the days of her postwar salon at the 'Pink House' in Darebin. Lina was Ian Fairweather’s key protector and patron; she supported many young artists, and she connected people across the cultural scene. Jelinek, who arrived in Australia a penniless 'architectural refugee' (as he put it) from Communist Czechoslovakia, had few friends or connections. When the two met in 1954, he was spending much of his time working as a builder on the Snowy Mountains Scheme.

Bryans had already emerged as perhaps Melbourne’s leading progressive portraitist, undertaking a long series of oil paintings from the end of WWII. Her subjects included the writers Alan Marshall and Jean Campbell, the painters Harald Vike and Guelda Pike, the academics Nina Christesen and Nettie Palmer, the curators Laurie Thomas and Robert Haines, and 'the Phillip Adams of his day', Adrian Lawlor (see Gillian Forwood, The Babe is Wise: the Portraits of Lina Bryans, 1995). Although she had little formal training, Bryans is admired for her intuitive gift for portraiture and the experimental landscapes of her later career. A well-travelled admirer of the School of Paris (she had met Picasso in person), her style stood somewhere between the colourism of Paul Cézanne and the Fauve brushwork of Henri Matisse or Albert Marquet. Each of Lina’s portraits tries a different gambit in attempting, like Chaim Soutine or Oskar Kokoschka, to seize the spirit as well as the appearance of the sitter.

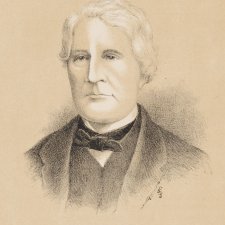

Yellow Portrait is true to form. One of the largest portraits she attempted, the work is like a Chinese brush painting, where much is suggested, but little described. Bryans often experimented with the aesthetics of the incomplete, following the example of Cézanne (another well-to-do experimenter with no need to sell his paintings). If the marks on the canvas were sufficient to capture the sitter in the desired aspect, the painting could be considered a complete work of art. In Yellow Portrait Bryans shows Alex in the creative act, focused intently on an unseen design on his drawing board. The vivid yellow ground envelopes the designer at work in an atmosphere of focus and optimism. As Forwood writes, "The bold drafting, with no spare brushstrokes, reflects the ‘all or nothing’ character of the subject". Mundane details of Alex’s desk are no more than hinted at by a brush drawing in brown paint, heightened at the shirt collar with white; one sees with a shock that the sitter’s right arm is absent. Bryans emphasises Alex’s trademark spectacles, self-designed and made up for him by a Hungarian optician in downtown Melbourne. When Lina chose to exhibit the work as Saturnid at the Independent Group of Artists Exhibition in October 1955, prominent critic Alan McCulloch in The Herald welcomed it (along with Lina’s portrait of Allan Marshall) as 'productions of a vigorous and inquiring intellect.'

We cannot suppose the picture, by far the sparest of Lina’s usually richly-painted portraits, stalled due to mischance. The artist’s grandsons Paul and James Bryans point out the yellow portrait of Alex was on view for decades in successive Bryans-Jelinek homes. First amid the timber renovations Alex designed for Lina’s modest terrace on Hotham Street, East Melbourne, then from 1957 in the front foyer of the grand Victorian home at 39 Erin Street Richmond (for which Jelinek designed an outstanding rear extension c.1964), and finally at the entrance to Bowen Street in Kew, where the couple lived into old age. Yellow Portrait always held the place of honour.

From a family of Czech master-builders in the regional capital of Hradec Králové, Jelinek had qualified as a builder before doing postgraduate study in architecture at the élite Special School of Architecture at Prague’s Academy of Fine Arts. His professor was the leading Czech modernist, Jaroslav Fragner. Born in 1925, Jelinek had grown up during the flourishing of the Czech Functionalist and international modern architectural movements, where the buildings of Josef Gočár, Adolph Loos, Mies van de Rohe, Ladislav Zak and Fragner were part of the modern urban landscape. His training in Prague, however, was truncated by the 1948 Communist takeover, which abolished private architectural practice. Jelinek fled with an engineer friend by hijacking a light plane in the factory town of Most and forcing the pilot to fly, seemingly at gunpoint, to Weiden in NATO-occupied West Germany. In 1950, as a registered Displaced Person who signed a two-year labour contract with the Victorian Government, he arrived in Melbourne.

The few known facts of Jelinek’s first Australian years were that he worked as a labourer laying track at the Newport Power Station, and then as a draftsman for an architect, designing neo-Georgian mansions in Toorak. Like hundreds of other skilled post-war émigrés, he found work in the bush on the Snowy Mountains Scheme. In awe of the engineering marvels he helped build, he was promoted to Leading Hand, and drew architectural fantasies in his spare time. He related that he was 60 metres up a scaffold at the Guthega Dam when Lina and the writer Alan Marshall drove up to tell him of his first architectural commission.

The year was 1956, and his first client was Bruce Benjamin, a Melbourne and Oxford-trained philosopher and Lina’s second cousin, who had been teaching at ANU in Canberra. The house that Jelinek designed for the Benjamin family still stands (if somewhat altered) at 10 Gawler Crescent Deakin, and is protected by A.C.T. Heritage. The judges who named it House of the Year for 1958 remarked of the building: ‘while representing a clean break with traditional construction and design methods, for its site, [it] had the appearance of belonging and in a way expressed the open-hearted character of this country.’ The house was widely published at the time in twelve black and white photographs commissioned from the Berlin-trained Wolfgang Sievers (National Library of Australia collection), who in 2002 still considered it ‘the most beautiful private house ever built in Australia.’

Although Jelinek built very little, he drew and designed a great deal at home, and seems to have been the ideal partner for Bryans. In the 1960s he drove her, in their trusty Land Rover, on many painting trips. These ranged from Mallacoota in Gippsland to Kata Tjuta in the Western Desert. Around 1973, for medical reasons, she was advised to move to central Australia for the dry climate. The couple lived in Alice Springs for two years, and after returning to live at Bowen Street in Kew continued to drive out to the desert when her failing health allowed. Alex used the Kew house as a workshop, where he made several large sculptures cut from heavy sheets of aluminum, displaying them in the garden (Quill, 1974 is in the National Gallery of Victoria). As an inventor, he built an experimental device for generating power by harnessing wave motion, and a unique all-aluminium bicycle that the hardy Jelinek rode from Melbourne to Coopers’ Creek, South Australia. He received several architectural commissions after 1960, but only one was built: the Peregian Roadhouse, a steel, glass and concrete pavilion for the Victorian real estate firm T. M Burke, used as a land sales office and café just south of Noosa. (see R. Benjamin, “Prague on the Sunshine Coast”, Fabrications, March 2012). Several other private villas and one public building (for the Mornington Art Gallery) remained unbuilt because Jelinek clashed badly with his clients. The title Bryans had first used for her portrait, Saturnid, was perhaps prophetic: Jelinek had a saturnine temperament, and could be an irascible perfectionist. In a more positive sense, the word ‘saturnid’ also refers to a species of large and splendid moth, often yellow in color like the canvas. From the rugged cocoon hatches a thing of beauty: certainly a fair prediction for the young designer in 1955.

A delightful collaboration between the painter and the architect can be published here for the first time . Based on his bold charcoal drawing dated 1953-55, Jelinek made a three-dimensional model of his futuristic design for a new Anglican church at Adaminaby. This was the town that was famously relocated to higher ground (beginning in 1956) to make way for the vast Eucumbene Dam, centerpiece of the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme.

Jelinek’s drawing features concave shells of reinforced concrete and a white spire towering over forty metres high. The meticulous model reveals the interior as a single vaulted space with diaphanous screen walls, and a great ceramic mural sketched in blue, red and yellow in due Fifties abstract style. The model and Lina’s landscape painting were placed together to make a simple diorama, with fresh foliage cut from the garden providing a foreground. Lina, who painted a number of exceptional landscapes of the High Country (see G. Forwood, Lina Bryans, Rare Modern, Melbourne 2003) painted the Adaminaby hills in this canvas. Alex engaged his friend Bruce Benjamin to present the project to the popular left-leaning Bishop of Canberra and Goulburn, Ernest Burgmann. Although far-sighted, neither Bishop Burgmann’s vision nor his church’s resources stretched as far as funding such a grand modern church for a remote tourist village.

Although Jelinek’s model survives in his estate, the limpid Bryans landscape has yet to be rediscovered. Happily, however, Yellow Portrait, the couple’s first collaboration as sitter and as painter, is now at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra, a fitting tribute to a distinctive moment in Australia’s cultural history, and to two very private lives.