On 8 October 1931, after months of failing health, General Sir John Monash died from coronary vascular disease in his home, "Iona", in Toorak, Melbourne. He was 66. Three days later, an estimated 300,000 people assembled under a calm grey Melbourne sky to honour the late general in a state funeral.

Monash’s body had lain in state for two and a half days in Queen’s Hall in Victoria’s Parliament House before being escorted in a funeral procession past the Shrine of Remembrance, where a special ceremony was held, to Brighton Cemetery. Monash was buried with full military honours in a Jewish service on 11 October. Speaking on behalf of the Federal Government, General Sir Harry Chauvel described Monash as one of the country’s most eminent citizens and servants: "We mourn Sir John Monash as a great soldier and a great citizen."

Already well known in Melbourne, Monash came to national prominence after his successful command of Australian soldiers on the bloody battlefields of the Western Front during the Great War. But he was not a full-time regular soldier, nor was he some military martinet. He was an engineer; a citizen-soldier; a businessman; a scholar; and a patron of the arts. He was highly intelligent, with at times boundless energy and drive. Monash could also be vain, abrasive, and self-promoting. Yet his many accomplishments could not be denied. A century on, Monash’s reputation is still celebrated; he is probably the best-known and most honoured Australian who served in the Great War. Yet some commentators continue to assert that Monash has been forgotten or insufficiently acknowledged.

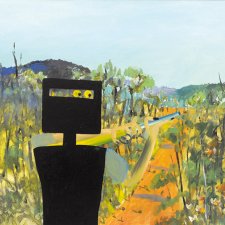

Monash was born in Melbourne on 27 June 1865 to Prussian-Jewish parents. The family later moved to Jerilderie in New South Wales; Monash later boasted that as a boy he had had a brief encounter with Ned Kelly. He alleged that the bushranger gave him "much sound advice", though he never elaborated upon the details of their conversation. Returning to Melbourne, Monash excelled academically, attending Scotch College and studying engineering, arts, and law at the University of Melbourne. He later worked as a civil engineer and businessman, and, after several passionate romances, married Hannah Victoria "Vic" Moss in 1891. According to Monash's biographer, Geoffrey Serle, the couple’s seemingly incompatible relationship was based on a "deep attraction", with the two constantly fighting and making up. Bertha, their only child, was born in 1893.

Monash also soldiered part time as an army officer in the Militia, Australia’s small part-time army. He enlisted as a private in 1884 while studying at university. Subsequently commissioned as an officer, he had some 30 years military experience prior to the outbreak of the Great War. Monash’s service, though, was atypical, in that he commanded artillery, intelligence, and infantry units. As soldier–scholar Peter Pedersen has shown, this diverse experience gave Monash firsthand knowledge of weapons such as heavy artillery and machine-guns, complementing his civilian surveying and engineering expertise. He would later draw on this experience in advocating tactics that employed artillery and other arms to support the infantry. Monash considered that the infantry’s true role was to advance under the protection of "the maximum possible array of mechanical resource... guns, machine-guns, tanks, mortars and aeroplanes" rather than fighting its own way forward.

In August 1914, within a month of the outbreak of war, Monash was appointed commander of the 4th Infantry Brigade in the all-volunteer Australian Imperial Force (AIF). Landing at Anzac on 25 April 1915, Brigadier General Monash command his brigade no better or worse than any other commander during the Gallipoli campaign. Ultimately, however, Gallipoli ended in defeat and evacuation, and in 1916 most of the AIF moved to France to fight on the Western Front. Monash, however, was promoted to major general, and from July concentrated on training the recently raised 3rd Infantry Division. While the AIF’s other formations had learnt their trade in training camps in Egypt or in combat, the men of the 3rd Division were trained by Monash in superior facilities in England, and benefited from the latest battlefield information from the Somme.

Monash’s 3rd Division began moving to France in late 1916, and fought its first major offensive in June 1917 in the capture of the Messines–Wytschaete Ridge in Flanders, Belgium. Monash’s instructions for the attack were meticulous, complemented with detailed briefings for his officers and subordinates. “I want to leave nothing to chance”, Monash said. The capture of Messines Ridge was highly successful. Later in the year, the 3rd Division fought in the Third Battle of Ypres, helping to capture Broodseinde Ridge before suffering heavily in the failed attack on Passchendale.

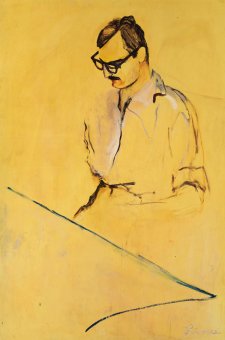

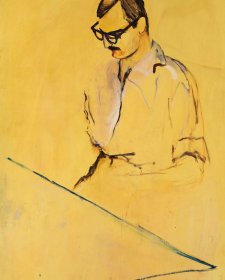

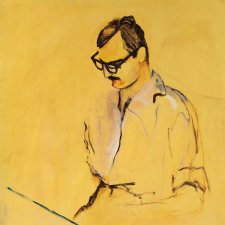

In early 1918, Monash sat for a portrait by official Australian war artist Lieutenant James Quinn. The London-based Australian painter had been granted an honorary commission in the AIF for a three-month appointment in France in order to produce works of several senior officers. Monash had been allocated as the subject for another artist, but when Quinn visited the 3rd Division’s headquarters at the end of February he seized the opportunity to paint the general. This caused some concern for those managing the war artist scheme, as Quinn also delivered the portraits of the AIF’s most prominent leaders, including General Sir William Birdwood, Major General Sir Neville Howse VC, and Major General Sir Cyril Brudenell White (now in the collection of the Australian War Memorial); rather than splitting the AIF’s principal officers among the Australian portrait artists, Quinn took “all the plums”.

In March, the 3rd Division was back in France when the Germans launched their great Spring Offensive. The German army initially broke through the British lines on the Somme, and threatened to capture the important railhead at Amiens. Monash quickly deployed his division to plug a gap in the British lines. The German offensive was blunted before Monash’s defensive deployment could be tested, but Monash was nonetheless praised for his quick and cool planning.

In mid-1918, Monash was promoted to lieutenant general and replaced Birdwood as the commander of the Australian Corps. Now leading the five veteran AIF divisions, he commanded some 166,000 men. He inherited a formation at the peak of its efficiency; the AIF was battle hardened, well trained, well equipped, and led by experienced officers and soldiers.

Monash’s elevation met resentment in some quarters. Australian-official-war-correspondent-cum-official-historian Charles Bean and the influential war correspondent Keith Murdoch tried to undermine the appointment, lobbying Prime Minister Billy Hughes to replace Monash with Brudenell White.

Although Monash was senior in rank to White, the opinion amongst the war correspondents was that Monash’s appointment to corps’ command was a “tragic mistake” as they believed him to be an administrator rather than a frontline soldier. Bean greatly admired White and rejected Monash’s "showmanship" and self-promotion. An element of anti-Semitism may also have been at work.

Monash silenced any doubters on 4 July with the Australian Corps' capture of Hamel. There, Monash’s meticulous planning - going well beyond the point of micromanaging - coordinated infantry, artillery, tanks, and aircraft to produce a stunning victory. With little modesty, Monash himself wrote:

A perfect modern battle plan is like nothing so much as a score for an orchestral composition, where the various arms and units are the instruments and the tasks they perform are their respective musical phrases.

Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, the commander of British forces on the Western Front, thought highly of Monash, describing him as "a most thorough and capable Commander who thinks out every detail and leaves nothing to chance".

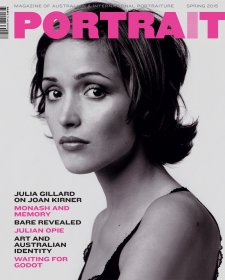

A month later, on 8 August, the Australian Corps spearheaded the British offensive in the battle of Amiens, capturing 7,900 German prisoners and more than 170 guns for the loss of 2,000 Australians. Writing home three weeks later, Monash proudly told his wife how his corps captured some 10,000 prisoners from 75 different German units. The Australians had been "fighting every day, gaining ground every day, and capturing prisoners and booty every day". In the same letter, Monash mentioned that "Quinn the artist" had been at corps headquarters working on "the replica picture which is destined for you". Monash thought this second portrait was "very much better" than Quinn’s earlier work. (The earlier portrait is in the Australian War Memorial’s collection. The latter "replica picture" remained in the Monash Bennett family until 2007, when it was donated to the National Portrait Gallery.) At the time, Monash was also sitting for another official war artist, Lieutenant John Longstaff. Like Quinn, Longstaff was working on multiple portraits of Monash. "It is very trying work indeed sitting for these artists," Monash commented. "I can only give them from ten minutes to half an hour at a time, and it is an extremely tiring process."

With the German army’s defences cracking, Monash relentlessly drove the Australian Corps onwards - almost to the point of breaking - in a series of operations until October, when the AIF was finally relieved from duty. On 6 October, Monash went to London and spent the best part of a week in sittings with Longstaff for what was "a very tiring and boring business". Monash confessed:

Longstaff has gone to a very great deal of trouble and had a photographer along to take me in about thirty different poses. He [Longstaff] would not pose me himself but insisted that I should adopt quite a number of different natural, habitual poses; he merely corrected quite minor details as to the position of the hands and feet, etc.

Between 1918 and 1919 Sir John Longstaff painted four portraits for Monash: two portraits are kept in the Australian War Memorial's collection, one portrait is held by Monash University, and one at the Art Gallery of New South Wales Monash also sat for two hours for the Polish painter Leopold Pilichowski.

The war ended on 11 November with Germany’s defeat. Monash was appointed Director General of Repatriation and Demobilisation to oversee the return to Australia of some 180,000 soldiers from France and Britain. Monash enjoyed celebrity status in London; he had more portrait sittings with Longstaff and Quinn, as well as with Australian portrait painter Isaac Cohen (currently in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria), sculptor Dora Ohlfsen, and British artist Solomon J. Solomon. He attended numerous social engagements and the theatre. His regular companion was Melbourne expatriate Elizabeth Bentwitch. Known as "Lizzie" or "Lizzette", she was a friend of Vic Monash and had been the general’s lover since late 1917. Their affair cooled, however, with the arrival in London of Vic and Bertha Monash in April 1919. Thereafter John Monash saw his mistress only when she was in the company of his wife.

The Monashes returned to Australia in late December; soon afterwards, in February 1920, Vic Monash died from cervical cancer. Bentwitch arrived in Melbourne the following September, and remained Monash’s close companion. They regularly attended the opera, and Bentwitch encouraged Monash’s collection of work by Australian artists such as Longstaff, Arthur Streeton, Tom Roberts, and Norman Lindsay. In addition to this collection of etchings, paintings, and war memorabilia, Monash’s home contained a library of several thousand books.

Monash remained a prominent public figure for the rest of his life, heading the State Electricity Commission of Victoria and taking up the vice-chancellorship of the University of Melbourne in 1923. He was promoted to full general in 1929.

Monash was an extraordinarily successful commander. His wartime memoirs, The Australian victories in France in 1918 (first published 1920), and the publication of private letters home, first in the press and then as the edited volume War letters of General Monash (first published 1936), helped make his reputation. Some historians and commentators have lauded him as the greatest allied general of the war, the man who single-handedly defeated Germany.

Charles Bean held a more nuanced assessment. He and Monash had clashed during the war, and the two maintained a cordial post-war relationship. Privately, Bean thought Monash "was neither a hero, nor a mighty strategic genius, but an extraordinarily careful and versatile organiser - which was precisely what the interests of his ... men ...demanded, at a very difficult and critical time." Peter Pedersen believes Monash’s skill lay in his technical mastery of all arms and tactics; he was a successful trainer of men who created and maintained an esprit de corps among those he commanded. However, as Pedersen rightly notes, Monash is all too often discussed in isolation of his contemporaries. There were other divisional and corps commanders in 1917-18, such as the Canadian General Sir Arthur Currie, who were as capable. It should also be remembered that Monash commanded a corps in action on the Western Front for the final six months of the Great War.

Monash received numerous British Imperial and foreign honours and awards for his war service. There have also been many posthumous memorials and tributes to his memory, including the establishments of Monash University and the Monash Highway in Melbourne. His name was taken for the small South Australian Riverland town of Monash, as well as a Canberra suburb, and his likeness currently graces the Australian $100 note. It is erroneous to claim that Monash has in some way been forgotten; his reputation and legacy is enduring. General Sir John Monash was, by any measure, an outstanding Australian.