For centuries, portraiture has been associated with the hand rendered image, laboriously painted in coloured muds suspended in organic mediums, either plant oil or animal glue, or drawn with soft stone or burnt sticks; indeed, it has incorporated techniques and technologies as old as human culture. The invention of photography at the beginning of the nineteenth century changed that, with machine-recorded portraits providing greater objectivity and realism, and a faster and cheaper process. And now, after nearly two centuries of photography, there has been another revolution that is just as profound, yet still essentially unexplored, with the advent of digital technologies.

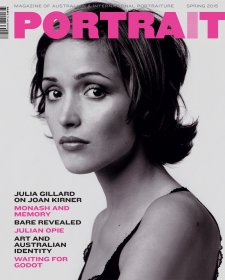

In today's digital world, what might a portrait look like? Most, to be fair, continue the fine art traditions of yore, or extend the tropes of photography, but with the understanding that photography is no longer bound by objectivity and can be manipulated beyond reality as easily as painting. While oil on canvas or cast bronze sculpture were the prized mediums of art in the past, the new mediums are no longer exclusive, but the ubiquitous tools of 21st century domestic and office culture - computers, screens and software. One of the masters of the new technologies and most celebrated exponent of digital portraiture is British artist Julian Opie.

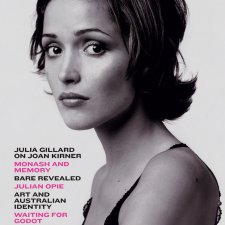

Julian Opie’s stunning Warhol-inspired portrait of British band Blur, for the cover of their album Best of Blur, made him the poster boy of the post-pop, 'Cool Britannia' generation in 2000. Opie had been a force in British art since the 80s with his funky hand-painted sculpture of common objects, but the cleanly designed portraits announced in the Blur cover, characteristically drawn using sharp black outline to separate areas of uninflected colour, became his signature style. Like his Pop art predecessors, Opie's work draws on popular culture, utilising the clean line and bold colours of signage, billboards and newspaper advertisements, as well as the arresting clarity of comics (Hergé, creator of Tintin, is much admired by Opie) and Japanese woodblock prints. The example of Patrick Caulfield and Michael Craig-Martin (for whom Opie worked for a short time as a studio assistant) may also have been relevant to Opie's development, as both of the older artists depicted simple objects in black outline.

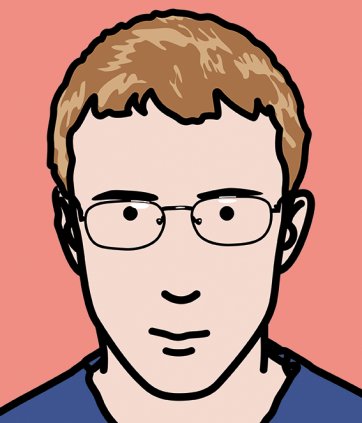

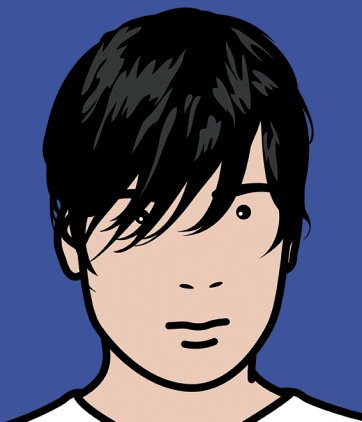

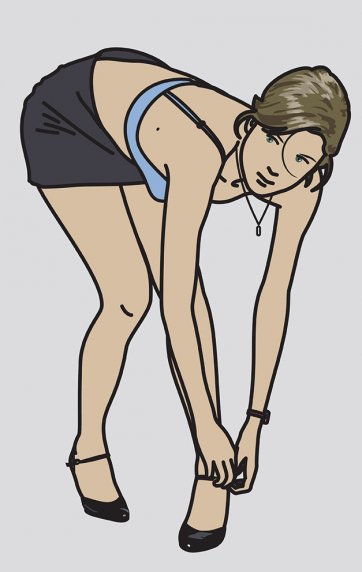

Opie's work simplifies his environment to graphic, outlined forms that are simultaneously schematic and individual. His portraits of the rockers in Blur, or musician Bryan Adams, Formula One driver Jacques Villeneuve and others are far from realistic: eyes are mere dots, two smaller dots indicate nostrils, and the mouth is an equally perfunctory affair- simply a pair of lines. Despite the severe economy that excludes detail, these portraits are recognisable and exude personality, surmised, rather than dictated, from clothing, pose and gesture. Opie's simplifications first began when he wanted a contemporary image of the figure: 'I consciously looked around for a way in which I could draw [people] and it started by buying the aluminium symbols for male and female toilets, and I looked at them and thought I could combine, as I often do, the impersonal with the personal.' The stripped back approach was eventually applied to portraits, making it easier to create the series of moving images, for example, Keira with pendant 2005, shown at the National Portrait Gallery in the exhibition, Present Tense, in 2010.

Keira with pendant is similar to a group of portraits made by Opie, all seemingly static line drawings which surprise with limited movement. In these screen based portraits, eyes would blink, jewellery would glitter, a pendant might swing. One of the most compelling of this type is the self-portrait in the National Portrait Gallery in London. The movement of the artist in this near life size image is very subtle, barely apparent in this gallery of painted portraits. He blinks occasionally, and his chest fractionally expands; the slight movements convey less the appearance of life in what is clearly a cartoon like drawing, and more of an impression of realism through detail. Opie has said that he got the idea for the limited movement when watching video games - the sprite for Lara Croft, protagonist for the popular Tomb Raider games, when left unattended, was programmed to perform a simple routine of idle movements that suggest a person at rest. In Opie's digital portraits, the twitch of an eyebrow, the movement of an earring or the ghost of a smile maintain the attention of the eye of the viewer to the almost schematic face, and somehow convey something personal in an impersonal image.

The popular gauge of quality in a portrait was that 'the eyes seem to follow you around the room', parodied in B-grade horror films where living eyes lurk behind an inert canvas to look back at the viewer. Opie's portraits don't belong on the walls of the Adams Family home or the halls of Hogwarts; there is no creepy sensation of the uncanny. 'I have drawn a lot of portraits', says Opie. The format has been passport style close-up. I wanted the bare essence of a face, a presence. 'However, I am always looking for ways to expand on the logic of the works I have made in order to make new works.' Opie's logic maintains the essence, but adds the signs of life without losing the appearance of artifice. In her 1964 essay, ‘Notes on “Camp,”’ American writer Susan Sontag attempted to define the change in attitude regarding art and culture in Western society. According to Sontag, in our increasingly unnatural world, we ‘see everything in quotation marks’ and ‘convert the serious into the frivolous.’ Opie's work looks like art, not a person.

His adoption of the strategies and technologies of 21st century marketing and advertising give his work a post-Pop sensibility. In their art, Pop artists such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein echoed their own times, the 1960s, using images of commercial products and other objects in the contemporary environment, depicting them with the production means of the day, Ben Day dots and screen prints. Opie treats the environment around him as the product, packaged and commercialised, and in turn uses the digital media of his day - digital photography, computer drawing and animation, LED screens, even lenticular cells - for his works. Critic Dave Hickey has stated that 'Painting isn’t dead except as a major art. From now on it will be a discourse of adepts, like jazz.' Opie still paints (and he collects old master paintings) but his work over the last two decades has come from a love affair with the digital world.

His portraits start as digital photographs, easily transformed and altered in computer applications. 'I play with images and then I define them as objects, so the portraits exist [only as] digital files, and at that point I don't deem them to be art works yet.' By tracing the photographs, Opie reduces features to essential lines and broad colours, poster-like and ready for a variety of outputs including animation. While the tiny actions are captivating, the acute stylisation of the portrait makes the subtle movements - the blink, the twinkle, the smile - something of a shock. Equally, however, the slight moves stylise the simple rhythms of life, announcing the fugitive and fragile aspects of the human machine in the digital age.

Has Opie, in his use of contemporary digital technologies, taken portraiture on a new road? We live in an image-saturated, multi-media environment. The digital world today seems a heaving sea of information technologies, from the agitating LEDs of Times Square, to Twitter feeds, Instagram and instant messaging, email and a host of image, sound and text downloads used to create virtual environments and on-demand entertainment. It sometimes feels like the institutions of mass media, commerce and advertising are now occupying much of the terrain formerly held by traditional culture and fine art. Opie works within this sphere, adapting his work to the culture of contemporary production.

Opie's shy animated gestures seem contradictory, given the static and oddly impersonal faces that he makes, each portrait as bold and as confident as a marketing campaign. Yet Opie doesn't sever ties with the past: art and the ideal are linked; art and society are equally linked. Julian Opie teases out the flicker of a smile within the electronic noise of today.