The Wentworths, who lived at Sydney’s famous Gothic Revival style Vaucluse House, were the subject of both scandal and praise in colonial Sydney. Long before their family home became the country’s first house museum in 1911, Wentworth rose to prominence for his expedition across the Blue Mountains, his political pursuits and pride in his country. His wife, however, was shunned from society. While it was customary for women to be precluded from social gathering, her ancestry and the fact she lived at a distance from the city, reinforced her isolation. This dichotomy reveals colonial attitudes towards marriage, ancestry and gender. Both were the children of convicts, but having two children out of wedlock, it was Sarah Wentworth who bore the brunt of the disrepute in conservative colonial Sydney.

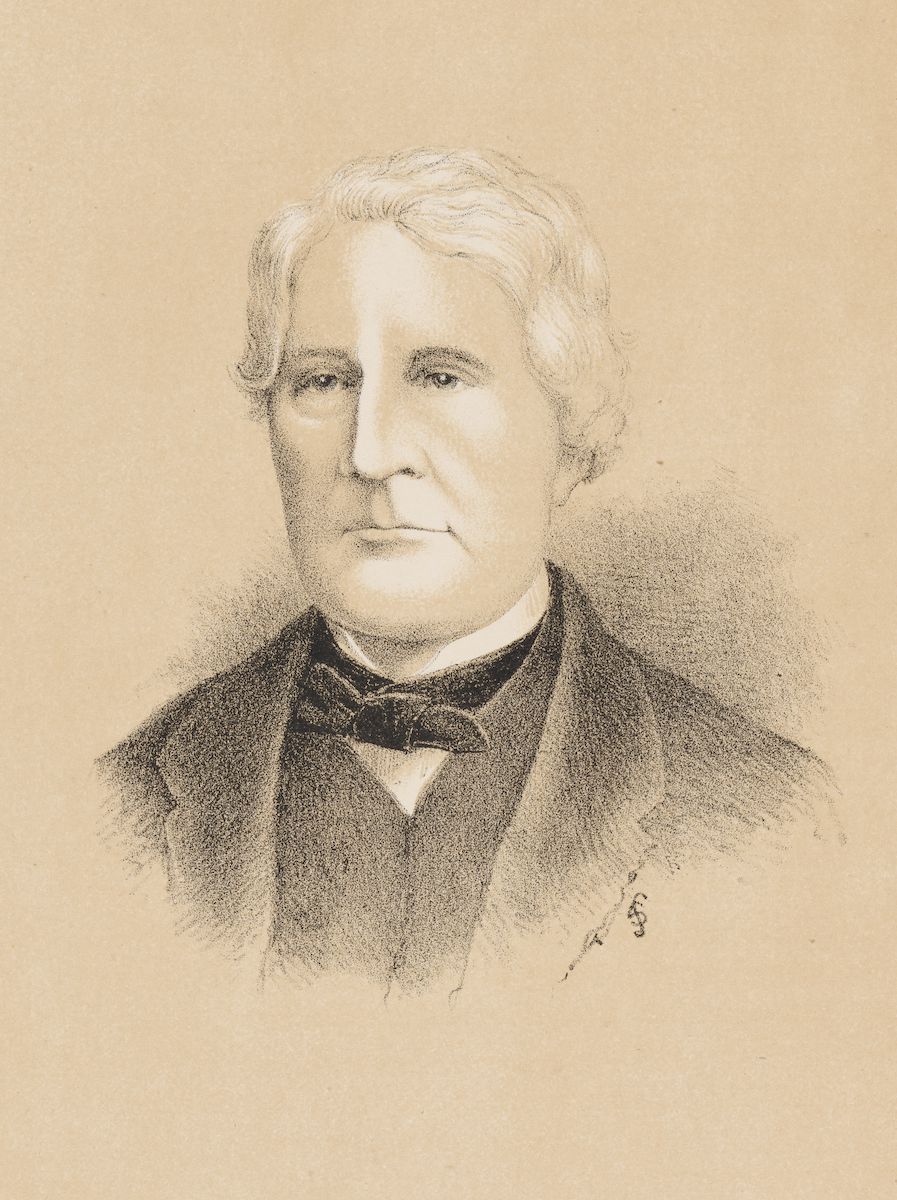

Portraiture, it could be argued, is as much about concealing as revealing. During Antiquity, the portrait profile and bust were considered dignified ways to preserve one’s image for posterity. This ethos informed portraiture during Australia’s colonial Australia. Portraits of colonial statesman William Charles Wentworth (1790-1872) and his wife Sarah Wentworth née Cox (1805-1880) each employ Classical conventions to create portraits that suggest wealth and power. But neither captures the couple’s controversial past.

Interestingly, it was her husband, not her, who was born out of wedlock. William Charles was conceived on the convict vessel Neptune in 1790. His mother, Catherine Crowley, was travelling to Australia following her 1788 conviction for stealing ladies’ apparel. Her soon-to-be lover, D’Arcy Wentworth – an Englishman of aristocratic descent – was also on board, serving as the ship’s doctor. Despite his noble ancestry, the elder Wentworth was not exempt from the criminal stain; he had a reputation for highway robbery and petty theft to make up for his financial shortfalls. In 1790, Crowley and Wentworth, unmarried, settled at Norfolk Island, remaining there until Catherine’s death a decade later.

Notwithstanding the stain of convict associations and illegitimate birth, Wentworth enjoyed a comfortable lifestyle. After his mother’s death, Wentworth was sent to England where he received first-class tuition before returning to Sydney in 1810. He capitalised on social connections when, in 1813, together with William Lawson and Gregory Blaxland, he led the first European party to cross the Blue Mountains. Receiving public acclaim and having Wentworth Falls named after him, the expedition propelled Wentworth into the limelight at the age of 23. However, success as an explorer was just the beginning; the future statesman had his sights set on further fields of endeavour.

Wentworth’s future wife, Sarah Cox, did not share his public profile. The Australian-born daughter of convicts, her parents had completed their sentences at the time of her birth in Sydney in 1885. Her father, Francis Cox, worked as a blacksmith and the family lived at Sydney Cove. As he had a wife and family in England, he never married Sarah’s mother Frances ‘Fanny’ Morton, who assumed the name Mrs Cox for the sake of propriety. The descendant of convicts, Sarah Cox was labelled a ‘currency lass’, a derogatory term European settlers used for Australian-born children. It was combating this scorn by showing pride in his country that her future husband, a ‘currency lad’ himself, championed.

Wentworth’s patriotism emerged during his campaigns for New South Wales to become self-governing. This conviction became action when, in 1819, he penned a legal tract, A Statistical, Historical, and Political Description of the Colony of New South Wales and Its Dependent Settlements in Van Diemen's Land, With a Particular Enumeration of the Advantages Which These Colonies Offer for Emigration and Their Superiority in Many Respects Over Those Possessed by the United States of America. In his 2009 biography of the colonial statesman, Andrew Tink notes that the issuance of the influential tract made Wentworth the first Australian-born individual to be published. By the mid-1820s, on the heels of this publication and after several years studying at Cambridge University, he was one of the leading barristers in the colony.

It was Wentworth’s prominence as a barrister that brought the nineteen year-old Sarah Cox into his life. Sharing her future husband’s determined nature, Cox employed Wentworth as her lawyer in her 1825 ‘breach of promise’ lawsuit against a Captain John Payne, who had retracted his proposal of marriage. Her court case against Payne was the first of its kind in the colony, and became the subject of scandal, particularly when awarded in her favour. The drama did not, however, end with the trial. Wentworth’s name was soon dragged into the controversy as his romance with his client became apparent.

Public opinion of her as a fallen woman was confirmed when Cox testified in the witness stand that she was already carrying Wentworth’s child. Acknowledging the child as his own – as his father had done – Wentworth and Cox commenced a de-facto relationship. A few years later, they moved into Vaucluse House, a home that would become as famous as Wentworth’s political ideas. In what was then a one-room cottage that had been established by the Irish knight-cum-convict Sir Henry Browne Hayes in 1804, Cox lived a comfortable yet secluded life. Over time, the house was extended; Gothic Revival style outbuildings were erected, and the estate enlarged to 515 acres. The couple defied the critics and had another child together, before finally marrying in 1829, when the newly minted Sarah Wentworth was eight months pregnant with the third of their ten children.

The contrast between the isolated domestic sphere of Sarah Wentworth and the high profile of her husband continued throughout their time at Vaucluse House. As William Charles Wentworth gained fame as ‘the father of Australian democracy’ for his part in drafting the New South Wales constitution of 1853 – considered by historians as the model for Australia’s 1901 constitution – and as one of the founders of the University of Sydney, his wife remained an absent figure at public events. However, Sarah Wentworth’s biographer Carol Liston has observed that her role in managing the family home, overseeing the kitchen garden, and supporting Wentworth was fundamental to his professional success, and that of their children.

These included their daughters Edith, Eliza and Laura, who have been immortalised in a portrait by Hans Julius Gruber, Three daughters of William Charles Wentworth (1868), which hangs in the hall at Vaucluse House. Affectionately nicknamed ‘The Three Graces’ by family members, the painting portrays the Wentworth daughters as sophisticated and privileged young women; there is no hint of the scandals that coloured their mother’s life.

The sophisticated portraits of William Charles and Sarah Wentworth provide insight into their self-image. These include a medallion by eminent English artist Thomas Woolner RA produced in 1854, a copy of which is in the National Portrait Gallery collection, and a marble bust of Sarah Wentworth by Achille Simonetti (1885), that was on loan from Vaucluse House to the Gallery from 2008 until earlier this year. The portraits are examples of those the Wentworthsand their progeny commissioned of their family for display in their home, which had been transformed into an ‘elegant château’ during the 1830s and 1840s.

The Wentworths amassed a collection of furnishings and artworks from Grand Tours of Europe to decorate Vaucluse House. The mosaic floor of the dining room was thought, for many years, to be made up of tiles from the ancient city of Pompeii (the tiles were made in Italy in the nineteenth century). It is no coincidence that William Charles Wentworth, a devotee of Classical art and literature, is presented by Woolner in a format that pays homage to Classical art.

Indeed, the cultivated image depicted in Woolner’s medallion matches that of both Wentworth’s domestic environment and his public image. As art historian Deborah Edwards has observed, Woolner referenced Classical coins in his commissioned portrait medallions, combining this with the Pre-Raphaelite philosophy of “truth to nature”. In the medallion, Wentworth’s strong features suggest the gravitas of the man, and reflect the interest in physiognomy at the time. Indeed, his social prominence is reflected in the title of the lithographic portrait by an unknown artist in the Portrait Gallery’s collection, William Charles Wentworth: The Australian Patriot (c.1870)

Simonetti’s posthumous bust of Sarah Wentworth matches the portraits of her husband. The image of Sarah is that of a powerful and sophisticated woman, not the convict mistress she was often dismissed as. Art historian Deborah Edwards described Simonetti as “the most fashionable Sydney portrait sculptor of the 1880s”. In this portrait, as with the one of her husband produced as its pair, Sarah Wentworth is shown wearing Classical attire, and assumes a powerful pose. Her head is held high and turned at an angle, and she bears a confident expression. These portraits are thought to have been commissioned by their son, Fitzwilliam Wentworth, and were displayed in the Wentworth mausoleum until their transferral to Vaucluse House in 1928.

Liston notes that portrait busts of women were seldom produced in colonial Australia, as the Gallery’s collection attests. The existence of this portrait, therefore, provides some insight into the image of Sarah known to those around her. Indeed, at least two other portrait busts of Sarah were produced in plaster; one by Charles Abraham (ca. 1844), which is on display at Vaucluse House, and another by an unknown artist that is featured in records associated with the House.

It is a small watercolour portrait by William Nicholas that reveals the most about Sarah Wentworth. Depicted seated, presumably at her beloved home, she sits upright in an expensive pink silk dress, her hands resting on her lap. Her head is tilted down, and she gazes directly out to the viewer. Compositionally, Sarah’s body occupies the picture plane, promoting her image as the “Mistress of Vaucluse”. Nicholas portrays her as a strong yet refined woman.

The Wentworth legacy as an Australian dynasty has endured since William Charles and Sarah Wentworth’s deaths in 1872 and 1880 respectively. The recipient of the first state funeral in New South Wales, William Charles Wentworth was mourned by 70,000 citizens when laid to rest on 6 May 1873. In the twentieth century, he was championed as “Australia’s Greatest Native Son” by patriotic historian Manning Clark. By contrast, Sarah Wentworth’s death in England eight years later passed with little notice in Australia and her scandalous past was soon forgotten.

Although William Charles Wentworth continues to be heralded as a significant figure in Australian history, Sarah’s story has not been forgotten. Liston’s 1988 biography, Sarah Wentworth: Mistress of Vaucluse, made a significant contribution to revealing Sarah’s prominent position in her family and home, suggesting that she may well have been the strong and refined woman represented in Simonetti’s bust. As a result, visitors to Vaucluse House today learn of the woman who played a vital role in establishing the House and the Wentworth family legacy. Her story brings to life the lot of a colonial woman whose experiences were both extraordinary, yet representative of that of many ‘currency lasses.’ William Charles and Sarah Wentworth’s portraits exemplify how even the most refined works can act to both reveal and conceal their subjects.