In the bush there is a creature

And he’s got a bushy tail

He is not a kangaroo

Or a mongoose or a snail

He wears a suit and waistcoat

And the smartest shoes and socks

That’s Sebastian, Sebastian,

Sebastian the Fox.

You may never see Sebastian

He’s a cunning little fox

He is hiding in the cupboards

Or behind the hollyhocks

He’s as clever as Aladdin

And as sweet as Goldilocks …

That’s Sebastian, Sebastian,

Sebastian the Fox.

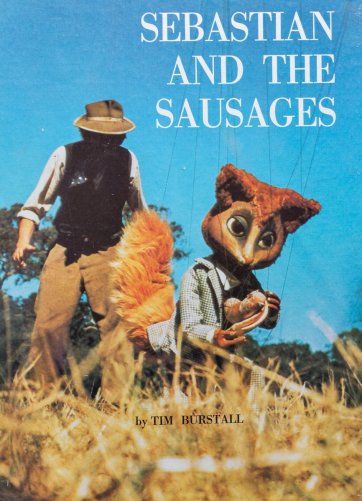

The marionette fox Sebastian dangles in a real landscape on the outskirts of Melbourne. Secreted in the real dry grass, stuffed tail aloft and aquiver, he watches a human actor playing a swaggie grilling sausages over an open fire. His diagonal eyelids narrow, and he makes his play, nabbing a snag, hurling sauce in the man’s eyes and fleeing, stiffly. In the ensuing pursuit, including a real-time chase across a log over a stream, he floats, tiptoed, up into a tree. Forced to the end of a branch, he falls, apparently to his death. Remorsefully, the swaggie retrieves his limp form, cradling him tenderly before laying him on the grass and resuming preparations for his meal. After some time, with a twitch of the tail, Sebastian revives – to steal again. The swaggie, relieved, chuckles at the audacity of the verminous hero.

Such is the simple tale told in the first episode of Tim Burstall’s Sebastian the Fox, ‘Sebastian and the Sausages’, which showed on ABC3 in Canberra on 22 July 1963 between the Test Card and the Eric Sykes show (followed by Dr Kildare). The many-stringed puppet was the creation of Peter Scriven, whose Tintookies had premiered in 1956 and whose stage show of The Magic Pudding made its debut in 1960. The episodes of Sebastian the Fox follow a reliable narrative pattern. Typically, Sebastian transgresses, and he suffers the consequences – poignantly; some time in the eighth minute, with a blink of his big eyes and a wave of his tail, he endears himself to his human antagonist. Alternatively, he’s simply captured or trapped in some way, and escapes. Sebastian’s movements inevitably want for fluidity but his operators, who included Igor Hyczka and Janet van Puffelen, gave him their all: in one episode the puppet rolls up a swag, in another he pumps up a tyre and in the climax to a story set in a grim Melbourne pet-shop, he hoists a genuine rabbit between his felt-and-wire paws.

Sebastian the Fox, an Eltham Films production, exemplifies the combined simplicity and sophistication of children’s entertainment in the 1960s; but it’s entertaining and instructive, too, in its reflection of the physical environment, and personal intersections, in the artistic milieux of inner-Melbourne and Eltham – on the rural fringe to the northeast of Carlton – in the 1950s and 1960s. The fox breaks into a potters’ cooperative in a whitewashed roughwalled outbuilding and clowns around on the wheel. Swinging rakishly from his own wires, he climbs the hayloft and throws eggs at the potters – played by real-life ceramic artists Peter Laycock (who had started selling pottery at Clifton Pugh's property Dunmoochin just outside Melbourne in 1960) and Tom Sanders (subject of a key Pugh portrait in 1957). Reprimanded, he atones by making some decent pots, and by the end he’s sharing pies with the men, his tail quivering with joy. He breaks into a painter’s studio – with a Pugh painting on its rough wall – and creates mayhem while a portraitist and his sitter take a break over tea. Barry Humphries, as the painter, compels him to clean up; but once he’s left, he and his subject, played by Rosalind Hollinrake, a wife of Humphries’s, are charmed by the self-portrait he leaves behind. The editor of the left-wing literary journal Overland, Stephen Murray-Smith (subject of a portrait by Fred Williams in 1980), appears as a diplomat in an episode about a bomb. The Age’s music critic, Dorian le Gallienne, wrote the theme tune, and the music for the sausage episode; after that, George Dreyfus supplied a stirring soundtrack that intensified the mischief, the suspense, the pathos and the eventual triumph.

Sebastian’s adventures are divided between the cobbled suburbs of inner Melbourne and the pretty country nearby – just like those of the members of the Victorian art crowd of the period (brought to life in Sally Morrison’s biography of Clifton Pugh, After Fire, Hilary McPhee’s introduction to the diaries of Tim Burstall, Memoirs of a Young Bastard and Graeme Blundell’s autobiography, The Naked Truth). From the days of the Drift in the early 1950s, Burstall and friends including Arthur Boyd and Clifton Pugh might be at the Swanston Family Hotel, Matcham and Myra Skipper’s lovenest in Grange Place behind the Russell Street Police Station, at Joe Hannan’s in Carlton or in Arthur Boyd’s father’s Dodge chugging up to the country where Eltham’s painting, sculpting and potting population was expanding in handmade homes on unsealed roads.

Sebastian the Fox pre-dated the establishment of the legendary Melbourne theatre, La Mama. In between, from 1965 to 1967, Burstall and his wife, Betty, were in New York, where he had had a Harkness Fellowship, studying with Paddy Chayevsky. She’d been exhilarated by productions she’d seen in makeshift experimental theatres there and on her return she was determined to introduce such a venue, with all that it might connote, to Melbourne. She found a space in Faraday Street, Carlton, and named it after a theatre she’d seen abroad. Graeme Blundell, who was in the first La Mama production in 1967, remembers Tim Burstall as ‘burly and, like Betty, often wrapped in hand-knitted pullovers’; he describes him jabbing the air with a stubby finger to make an incontrovertible point, talking close and pugnaciously, slopping his wine, guffawing and slapping his ‘meaty thigh’. As subversive theatre laid waste to the complacencies of inner Melbourne, Eltham continued to provide a complementary, ideologically compatible getaway for its practitioners and enthusiasts. Blundell and his ilk, in their ‘small, dank, Carlton actors’ houses … idealised the dreamy, fairy-like atmosphere of Eltham, the impression of festivity, and the idea of soul mates and artistically designed leafy salads … The Burstalls epitomised the Carlton understanding of Eltham as a haven for those who enjoyed art and language, adobe and rammed earth, and the use of indigenous plants and landforms in landscape design.’

In the 1950s, Tim Burstall lived in Eltham with his young family, but worked in Melbourne, where he was a speechwriter and public affairs officer in the Antarctic Division of the Department of External Affairs (Morrison and McPhee evoke the relatively hard lives of the women and children left up-country in half-built mud-brick follies during the week). He’d been commuting for some years when he decided to make a film on the weekends, the storyline of which was essentially boy wins goat, boy loses goat to rough rabbiter, boy gets goat back. Initially, using resources to hand in the office, Burstall tried using Sir Hubert Wilkins’s camera from 1930, but it was unsuitable and an alternative had to be hired. Gerard Vandenberg, a young Belgian photographer living in the area who had made portraits of the Eltham children, was his cameraman. Dan and Tom Burstall, and Marcus Skipper, son of sculptor and jeweller Matcham, played the young leads; and Matcham Skipper himself – described by Sally Morrison as the heart-throb of Eltham – played the rabbiter. The tracking shots were done from atop a VW belonging to Eltham’s resident mudbrick architect, Alistair Knox. The music was written by le Gallienne, another local resident whose home had been designed by Knox (and whose partner, Richard Downing, had been painted by Pugh). The Prize, as it was called, won an award at the 1960 Venice Film Festival. Burstall recalled that although his children, and his neighbours’, and his friends appeared in the film and at the time he and Betty actually had goats, ‘The Prize really grew out of memories of my own childhood, I guess, in England but grafted onto that was the kind of life that I thought my kids lived in Eltham at the time, which was pretty idyllic … they used to ride a horse to school … I think it is very beautiful in a very romantic and lush sort of way, the exact opposite of the usual cliché of Australian landscape, you know … the dustbowl.’

The Prize was the first production of Eltham Films, an enterprise founded by Burstall, at that time a Communist, and a friend of his, Patrick Ryan – who had money. Ryan and Burstall knew each other from Geelong Grammar. Ryan’s father, Rupert Sumner Ryan cmg dso, had been a student there before attending Harrow and the Royal Military Academy, whence he graduated with the sword of honour. While Ryan was deputy to the Earl of Erroll, High Commissioner to the Inter-Allied Rhineland Commission in Coblenz after the First World War, his sister, Maie, came from Australia to act as his ‘hostess’; but in due course he married the earl’s daughter, Lady Rosemary Hay. He became an arms dealer, working for Vickers, and in all likelihood a spy. In Australia, where the couple ended up after stints all over the place, Ryan acquired a thousand-acre property near Berwick, called Edrington, which he owned jointly with Maie. Edrington’s Arts and Crafts style house – now, the glittering nucleus of a high-end community for the aged – was built by a pastoralist in 1904, as a gift for a dancer named Fanny Dango. Over time, Rupert Ryan would build up the property’s livestock, pioneer flax production in Victoria and become United Australia Party member for Flinders. However, from the beginning, he neglected his wife and she took their son, Patrick, back to England with her. Maie Ryan married future statesman Richard Casey in London in 1926. Diane Langmore, in her biography of Maie Casey, relates that ‘Rupert allowed himself to be divorced – submitting to the humiliation of a contrived assignation at Brighton to prove his guilt – and in return Rosemary permitted him to bring Patrick back to Australia.’ She married again in 1935.

In accordance with the barbaric custom of his kind, Patrick Ryan was sent to board at Tudor House as a very young boy. From 1932, when he was seven or eight, he spent his holidays with Maie and Richard Casey – now treasurer – and their son and daughter at Duntroon near Canberra. He was close to Jane Casey, three years his junior, but to children, his aunt was legendarily frosty – or worse. According to Langmore, Maie intercepted letters to Patrick from his mother – ‘a startling example of the deviousness of which she was capable’. Cora Hancock, an English nanny, had come to Australia with Patrick, but she came to favour his cousin, Donn. So it was that ‘Patrick was perhaps the loneliest of the three children. Deprived of his mother, he received little attention or affection from his father, who never visited him at Geelong Grammar … Maie offered little comfort … Although Patrick continued to be treated as part of the family, Maie was as inattentive and undemonstrative to him as to her own children. She was absorbed in horse-riding, gardening and … painting.’ Caseys and Ryans, Conversation Piece 1938 shows Jane, Donn, Patrick, horses, dogs, a ginger cat and canaries against the backdrop of Black Mountain. In early 1949, the year he turned 24, Patrick married a socialite, Rosemary Chesterman, and the couple moved into Williams Road in South Yarra. For about three years, she studied art at the National Gallery School and the George Bell School. Then, in early 1953, Rupert Ryan died; the Argus reported that the bulk of Rupert’s estate of £163 520 went to Patrick Ryan, journalist. (That year, according to the website australia.gov.au, a new FJ Holden cost £1 074 drive-away – 68 weeks' wages for the average worker.) Langmore relates that ‘bowing to some pressure from Dick and Maie’, Patrick sold his share of Edrington to them at its mortgage value; henceforth Donn was joint owner of the property with Maie. Patrick and Rosemary were free to travel to England; she studied at the Chelsea Polytechnic in the mid-1950s. By the end of the decade they had two children; through the 1960s Rosemary exhibited in Melbourne. Rosemary Ryan is credited in an episode of Sebastian, in which the fox makes a mockery of the Best Dressed Man of the Year Parade in a wood-panelled Melbourne nightspot, packed with elegant smokers.

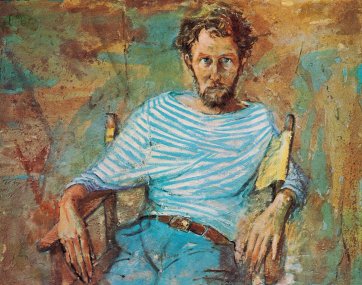

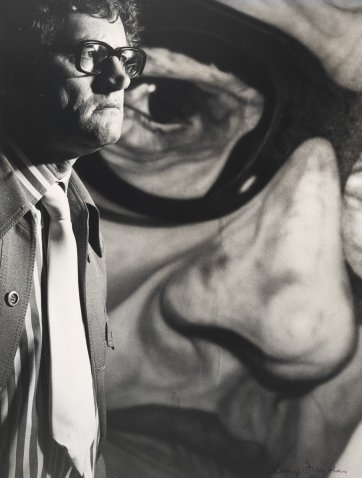

Burstall and Ryan were partners from 1960 to 1970; but in the historical record, Patrick Ryan is no more than an occasional name, hardly better-represented than Rosemary Ryan’s paintings are in the Art Sales Digest. Even in the age of Trove, from which no published secrets are hidden, it’s easier to find information about a Burstall than a Ryan (try it: Patrick Ryan, Paddy Ryan, Pat Ryan, Patrick Victor Charles Ryan). On the public record, all that exists about Ryan, now, is random information; for example, that Philippe Mora’s silent film, Dreams In A Grey Afternoon, featuring stop-motion animation of sculptures by Danila Vassilieff and ‘rare footage’ of John and Sunday Reed, was first screened at a party at the Ryans’ home in 1965 (the year Ryan’s uncle became governor-general). However, in this case, the equation between the written and the pictorial record doesn’t work out as expected. Of Tim Burstall, about whom very much is known, there are several good photographs, and a few more that are fuzzy but evocative; and there is, or was, a controversial Archibald-winning portrait. Of Patrick Ryan, we know very little, but his obscurity notwithstanding, there remain two sensitive painted portraits of Ryan by two of the best portraitists of his generation: Clifton Pugh and Fred Williams. Pugh painted him in 1965, and a few years later Mark Strizic photographed him; the photograph and painting are included in Involvement, a suede-bound volume of complementary portraits by Pugh and Strizic that even smells of Eltham. Pugh’s perspective on Ryan was that he was a ‘delightful man’, a ‘very romantic man who wants a great deal of drive.’ It may be the case that one way or another, men who have money get painted portraits; but men who ‘want drive’ don’t get obituaries, as a rule. Ryan doesn’t seem to have got any when he ran out of drive altogether at the end of the 1980s.

Following The Prize, in 1961 Burstall and Ryan released a film about the ceramic sculptures of John Perceval; the following year Ned Kelly: Australian paintings by Nolan won an Australian Academy of Television and Cinema Arts award. Sebastian was followed by a further series of short films about Australian artists. Black Man and His Bride: Australian Paintings by Arthur Boyd won the AFI Award Silver Medallion in the Experimental category; and then there were Australia Felix: Australian paintings by Tom Roberts; Sydney Blues: Paintings by Robert Dickerson; and The Crucifixion: Bas reliefs in silver by Matcham Skipper.

In 1965 Ryan produced a documentary, The Making of a Gallery, about the history and future of the National Gallery of Victoria. The 36-minute film is of the kind we watched as children in a Canberra government primary school, cooped in an airless room at the end of an upstairs corridor. To Australians in their fifties, the rolled r’s and long i’s of the narrator of The Making of a Gallery are as familiar as the voices of our family members. Surely the judgement ‘currriously modern’ dinned around our movie-cell, motes of dust revolving in the light from the projector and settling on the carpet tiles as the slithering violins, cymbals and sinister pulsing horns of the soundtrack drowned out the clack of the reel. Whether the colour was always off, or whether it’s gone off, is a matter for film historians, but as it stands, the whole of The Making of a Gallery is tinted pink. As the camera roves over paintings by Van Eyck, Tiepolo, Poussin, Pissarro, Von Guerard and Streeton the viewer is assailed by puce seas, rose rocks, pink clouds, mauve Israelites, Moses in a raspberry robe under a violet cloud, maroon horses tethered near the cherry canvas tents of the Heidelberg camp. Frenzied strings vibrate behind the woodwind section as the camera pans over works by Boyd and Drysdale. Dickerson calls for something jangling; a jaunty tune in an unsettling minor key accompanies Brack’s scurrying bureaucrats. We see John Brack himself, silently instructing a student at the Art School; the former NGV director Darryl Lindsay drags on a cigarette in his office; paintings are stacked and lean pell-mell in storage; a besuited curator, ungloved, pulls Blake’s engravings of the Divine Comedy out of a box and waves them in the air. The film includes fascinating footage of the gallery and its claret-coloured moat (‘fifty feet waaaide’) under construction. We see pinkprints of the building from various elevations. Bare-headed workers in low-vis singlets move around the site, artisans chip at bluestone blocks with chisels. Finally, the architect Roy Grounds appears behind his desk in a claret-coloured suit, issuing the last word on the spire of the concert hall: ‘The function of the spire is one of the functions of architecture: to create an emotional experience’, he growls. ‘Christopher Wren didn’t put spires on his churches to keep the rain out. He put spires on his churches to say to the population, “There’s something very important happening here.”’

A movement that seemed of the utmost importance was the subject of the last great documentary production of Burstall’s and Ryan’s Eltham Films: The Antipodean Painters, narrated by the same man or his clone, which provides an entirely fresh perspective, now, on the group about which so much has been written. The film opens with footage of the Antipodean exhibition at the Victorian Artists’ Society in 1959 and slides into a view of Clifton Pugh in his virile heyday, jabbing at the easel. It moves through works of Arthur Boyd, whose glorious Old Testament mural for Harkaway near Berwick is examined in detail, before panning around Percival’s small sculptures: ‘Laaaike some hideous cloud of heads from Hiroshima is the group called The Population Explosion’ the narrator bawls over a cacophony of discordant piano. Blackman is accompanied by ominous recorders. A flute tootles as Dickerson presents people ‘at their emptiest in their pursuit of pleasure, playing cards at the park, or sitting disconsolately at the beach … modern images of exhaustion and failure, each locked in his own priaaavate world.’ As for Brack, the sentence is intoned against a score of meandering flute and bongos: ‘It is hard to imagine a more incaaaisive attack on the complacency and vulgarity of suburban laaaife than in this picture of three Melbourne matrons.’

In the late 1960s, Burstall and Ryan made their first feature film under the Eltham badge: 2000 Weeks, now famed, as Graeme Blundell recalls, as the first great failure of the Australian film industry. Clips of the film can be viewed online. In the first, the young protagonist struggles with the pronouncements of his friend, returned from abroad: ‘One of my recurrent nightmares in London was of waking up and finding myself back in the old home town … The things I tried to escape from when I left – the hideous provincial attitudes of everyone the awful mediocrity – to me Australia’s always seemed a nation without a mind.’ Ultimately, the mild protagonist asserts himself: ‘You seem to me Noel – how shall I put it? – morally corrupt. You know there are a lot of people in this country who don’t want to be simply second-class Englishmen or Americans – people who want to build a life of their own. You’re doing your best to see they remain colonials: culturally, economically, in every way.’ Its pitiable air of commitment notwithstanding, the film seems, now, to be saying things that demanded to be said, clearly, by someone, somehow; but Blundell recalls that it was ‘literally laughed off the screen’ when shown at the Sydney Film Festival at the end of 1969 and that Burstall was devastated. In the autumn of 1971 he bounced back bruised with Stork, a vulgar comedy much of which was filmed in his own living-room in Nicholson Street. He formed a production company called Hexagon and soon after, as if to prove that he was done once and for all with the arthouse, offered Graeme Blundell the lead in Alvin Purple. The rest is Australian cinematic history. The party to celebrate the first box-office-record-breaking week was at the Burstalls’ in Carlton. Thirty-three years later, at a special screening of Sebastian the Fox ‘The Bomb’ at The Eltham Community Centre, Burstall was felled by a stroke which proved fatal the following day.