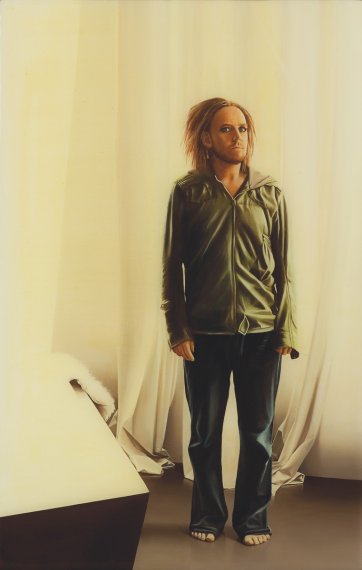

When Sam Leach won the Archibald Prize in 2010 with a portrait of comedian and musician Tim Minchin, the standard reaction was to observe how unexpected it was that such a small and meticulous work had so thoroughly trumped its brasher, bolder and mostly massive competitors. A mere sixty centimetres high and glazed with a layer of glossy resin, Leach’s winning work provided a delicate, jewel-like rebuke to what sometimes seems to have become standard portrait-prize fare. Firstly there was its arresting precision, the exacting application of paint, and a virtuosity of execution of the sitter’s features informed in part by the stimulus Leach finds in the work of Dutch still life and landscape masters, and in the seventeenth century generally as the period that saw the advent of scientific observation as a way of understanding the world. Demonstrating the influence of an artist like Willem van Aelst – known for his arrangements of flowers, fruit and dead game in which illusions of light, surface and texture are impeccably rendered – Leach’s portrait of Minchin, like many of his works, was an examination of the nature of painting itself, and of how something as fluid or indefinable as a ‘likeness’ might be convincingly constructed in paint. No gimmicks, just Minchin, barefoot, in a velvety-looking olive green hoodie, standing in a corner in a room in his home, angling his head slightly towards one shoulder and turning his darkly underscored eyes to look at you. Minchin quipped that he liked the painting because it made his lounge room floor look clean, and that would please his mother. In addition to aiming for an accurate depiction, Leach said that he ‘wanted to get a sense in the painting of the fact that he’s quite a deep, careful thinker’, and admitted that he painted three portraits of Minchin before arriving at one that he was content with.

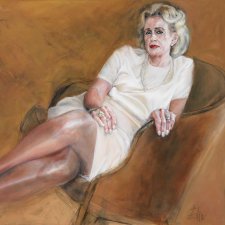

Then there was the portrait’s much commented-upon size. His fourth consecutive Archibald Prize finalist, Leach’s portrait of Minchin remains the smallest painting ever to have won it, as is so for the landscape with which he took out the Wynne Prize the same year – making Leach one of only three artists (the others being William Dobell and Brett Whiteley) to achieve that distinction. Of his typical choice to paint on a small scale, Leach has said that his intention is to create a sense of intimacy, to ‘draw the mind into the paintings’, as he puts it, and encourage the viewer to engage with them closely. ‘Instead of having the entire space exerting influence on the viewer’, Leach prefers to ‘have the viewer project into the space of the painting’. The application of epoxy resin to the surface of his paintings plays an important part in creating this effect. As Leach explained of his Archibald-shortlisted portrait of former Victorian premier Jeff Kennett, for example, ‘the work is small in scale with quite labour-intensive detailing to encourage an intimate and individual encounter with the portrait. The whole painting is coated in resin, which forms a reflective barrier. This seals the painting in so that it is completely isolated from the world around it. At the same time, the reflection draws the viewer into the picture.’

Since his first solo exhibition, in 2004, Sam Leach has made a speciality of these modest, lustrous and flawlessly-realised paintings that, in both execution and subject matter, are also often suggestive of museum collections or cabinets of curiosity, and evocative of the various precise, invasive or irreversible methods applied as a means of stilling life: banks of pickled organs, floating in metho or formalin; moths and butterflies impaled onto paper; and plants flattened in crumbly leather-bound folios. His works consider the Enlightenment-era assumption of humankind’s superiority over nature, and the capacity for exploitation inherent in it, exploring the relationship between humans and animals and the way that science and technology shape our perception and understanding of the world. Leach’s 2011-2012 exhibition The ecstasy of infrastructure, for example, featured paintings created in response to those by artists Ralph Balson and Edwin Tanner, Leach finding an affinity between their engagement with structure and abstraction and his own interest in elucidating where empirical method and art intersect. In Leach’s paintings, bats, birds and insects, apes, marsupials and various other creatures are depicted as if in observance of conventions of still life or natural history illustration, but with motifs – dots, or LED-style digits, perhaps – indicating modern technology, or juxtaposed with machines and abstract shapes. Chimps disport themselves, sometimes uncomfortably, in clinical, hard-edged settings; big cats are overlaid with prisms and targets; birds are reflected onto shiny surfaces as geometric structures; pandas and landscapes are revealed to be composed of cubist forms; and, in a series of paintings inspired by images from the archives of NASA, vultures, goats and other creatures inhabit labs and scenes alongside men in spacesuits, tinkering with various contraptions. To quote one curator’s description, ‘these wee paintings have always had a jarring element embedded beneath the lacquer’, a quality that spikes reflection on matters of knowing and scientific progress, and on the place or role of animals in the measures by which these states are achieved.

Though portraiture is only an occasional aspect of Leach’s output, his crafting of these sealed, intimately-scaled and thought-provoking paintings, in combination with the underlying concerns of his work, provides a particularly apposite approach for portraits, the act of looking at which is in itself a kind of investigation, search or discovery. Correspondingly, Leach’s paintings suggest the revisiting and remaking of another historical tradition – that of the cabinet painting, wherein a full-length figure or scene is shown in perfect detail and highly finished, but on a tiny, personal, or one-on-one scale. Collected in previous centuries by wealthy connoisseur types and typically displayed in little rooms, known as cabinets or closets, to which only intimates would usually be admitted, cabinet paintings made a perfect format for portraits in the old-school sense of the term: namely, a method by which the likeness, and purportedly the spirit, of a notable, desired or admired individual might be extracted and distilled into a cherished object, collected and preserved for posterity in much the same manner as a prized natural history specimen might be snared, stuffed, pinned or delineated. Disdaining the declamatory, in-your-face mode of some contemporary portraiture, Leach has devised a distinct, readily recognisable portrait style wherein his ongoing interest in ideas about art, society, humanity and nature coalesce with technical and conceptual rigour in works which elicit reactions such as inquisitiveness and empathy, and which invite or even demand intense, private scrutiny. You can stare at length at Kennett’s monolith-like face, rendered in remarkable detail and preserved alongside a similarly accurate depiction of a bird in flight, while Minchin, in a full-length portrait, stands as if awaiting inspection, but unerringly returning your gaze.

This characteristic of Leach’s work assumes particular pertinence in the case of one of his more recent portrait subjects, Dr Mandyam Srinivasan am, a scientist whose research focusses on the minds of insects and on the ways in which they might provide a model for an understanding of cognition and emotion in other animals, including humans. Professor of Visual Neuroscience at the University of Queensland’s Queensland Brain Institute, a fellow of the Australian Academy of Science and the Royal Society, and the 2006 recipient of the Prime Minister’s Prize for Science, Dr Srinivasan studies the way that insects – and bees in particular – see, think, learn and navigate, devising experiments whereby they are coaxed through mazes and other structures, trained to ‘read’ signs and symbols, or to turn left and right. The results of his team’s research to date have contributed to various projects relating to machine vision, camera technology and robotics, such as the development of autonomous navigation systems for aircraft for clients such as NASA and the US military. Incorporating motifs of Leach’s work – for example, the bee within a pattern of orange dots in the background, the Op Art-like design of the apparatus in the foreground, and, of course, the painting’s scale and resin-coated surface – the portrait of Srinivasan is the most recent work to have come about through the National Portrait Gallery’s commissioning program, a canny, double-edged strategy that initiates the creation of portraits of significant subjects by equally important contemporary artists. Various curatorial incumbents have previously described the process as a specialised kind of matchmaking, pairing the profession, stature or persona of the sitter with an artist whose style holds a strong possibility of a more insightful and resonant result.

In this instance, the artist’s seventeenth-century sensibility and interest in the scientific developments of the era is mirrored in a sitter whose work is a contemporary continuation of the quest for understanding, the pairing, and its small, stunning result proving more than usually serendipitous.