There was general rejoicing in the colony of Victoria when in mid-1860, Sir Henry Barkly GCMG KCB, the forty-five-year-old governor, married twenty-two-year-old Anne Maria Pratt, daughter of Major General Pratt, commander of the troops in the Australian colonies and New Zealand. The service, enacted at the raw, cramped Christ Church South Yarra, was discreet. The party comprised only the bride and bridegroom; Barkly’s daughter Blanche as bridesmaid; Pratt; Mrs Pratt; and Captain Foster, aide-de-camp to the major general. The Argus reported that the church was handsomely festooned with flowers, and ‘notwithstanding the secrecy preserved two or three hundred spectators, mostly ladies, were present … The nuptial knot was tied by the Bishop of Melbourne … The bride wore a white moiré antique dress, covered with white lace, and a rich white veil.’

Annie Pratt had lived in Madras for twelve years before coming to Victoria, and her husband was familiar with other parts of the world. Born in Rossshire, Scotland in 1815, Barkly started his career in business and politics before serving terms as governor of British Guiana and then Jamaica. Appointed governor of Victoria, he arrived in the colony on Christmas Eve 1856, just a few weeks after the first sitting of its newly-created parliament. Melbourne hadn’t yet turned twenty. Henry Barkly’s immediate priority was securing stable government – a challenge, as into the 1890s, as it transpired, the parliament was to comprise generally independent members who clumped and reclumped into factions according to the issues of the day, amongst them land settlement, education, constitutional and electoral reform and payment of parliamentarians.

Barkly’s first wife, Elizabeth Helen Timins, accompanied him to the colony of Victoria, pregnant with a child that was probably her fifth. She lost no time in impressing the public with her ‘frank and natural manner, feminine tact, and savoir faire’, with ‘the intelligent interest she manifested in the various public institutions and undertakings, to which her attention and patronage were solicited’ and with ‘the cheerful activity of her cooperation with other ladies in the work of charity’. A gold lead was named after her in January 1857; the Lady Barkly Company operated for years to come. However, only four months after her arrival in the colony, and at the age of thirty-seven, Lady Barkly died. The Argus reported that in the nine days following the birth of her son she ‘suffered from a nervous excitement, producing depression of spirits, fits of hysteria, and at length a complete nervous exhaustion, terminating in death’. The paper referred to the ‘uncertain state of her health, together with prostration of spirits, and a foreboding anxiety by which she was oppressed ever since she last quitted the shores of England’. When Augustus Tulk announced her death to the many readers in the Public Library on 18 April 1857 the institution was closed for the rest of the day by general agreement. In due course it was reported that her body was enclosed in three coffins, the inner stuffed with horsehair and lined with satin, the middle of lead and the outer of wood, two inches thick and covered with superfine black cloth. Affectingly, Lady Barkly was said to have chosen her own burial site, knowing she would not survive confinement. A couple of weeks after she died, her infant son joined her in her grave in the ‘new cemetery’ to the north of the city, opened four years before.

It was months later, in November, that the Age ran a sensational story, contributed by a columnist for the Australian and New Zealand Gazette, about Lady Barkly’s involvement in a vehicle accident on the Princes Bridge. ‘Lady Barkly was very fond of driving her own pony phaeton … She drove well. We all admired her elegant ease and simplicity of style. One day she was driving up the slope of the Princes Bridge just as one of the St Kilda omnibuses was coming down … suddenly the reins broke … The omnibus came in contact with her phaeton, which was overturned in an instant. Lady Barkly was taken up almost fainting. The driver was speedily seized.’ According to this account, the amiable lady declined to press charges, and the collision had been hushed-up because the she didn’t want the driver of the omnibus blamed for an accident. The week after its publication in Melbourne, ‘The Death of Lady Barkly’ was syndicated to the Sydney Morning Herald and the Newcastle Northern Times. Twenty-first century readers might find it incredible that an accident involving an omnibus and a lady would go unreported in the first instance. Yet we cannot know the extent of the discretion practised by the proprietors of newspapers of the day; perhaps respect for the governor, and his gentle spouse, was enough to keep the story out of print. Whether Elizabeth Barkly had an accident that set off a miscarriage; had an accident, but died of unrelated infection or birth trauma (‘milk fever’ or ‘post-partum inflammation’); or was never involved in an accident at all, will probably never be resolved, now.

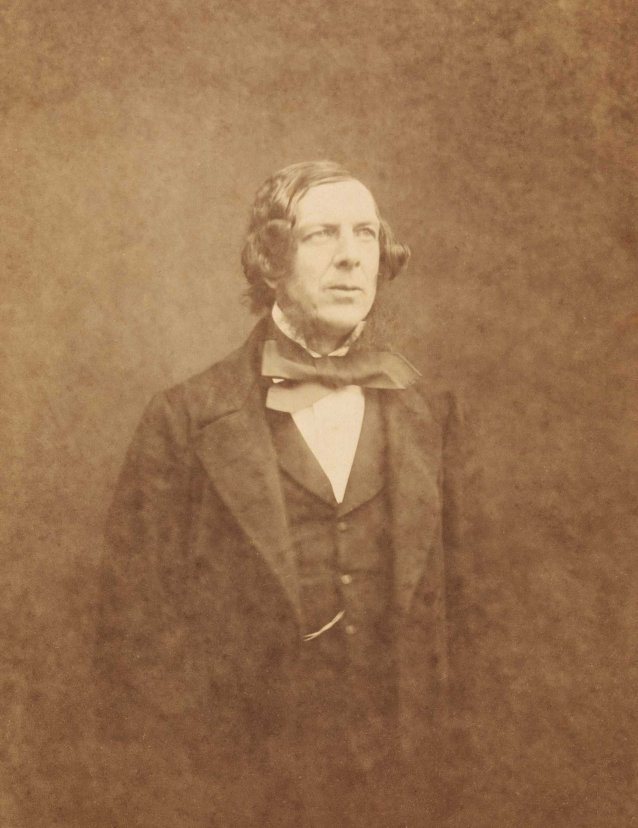

We know very well what Henry Barkly looked like. Even taking into account the fashions of the day, his facial hair – an unholy alliance of sideburns and gossamer beard strands with the chin left all-but bare – must surely have been remarkable. The National Portrait Gallery has several representations of Barkly in various mediums. One of them is a rare photograph by Antoine Fauchery, a Parisian artist and writer who was in Australia from 1852 to 1856, mining on the goldfields of Ballarat, keeping a store in Daylesford and running the Café Estaminet Français in Little Bourke Street. Having returned to Paris to publish Lettres d’un mineur en Australie he sailed back to Melbourne, where at the end of 1857 he established a photographic studio and collaborated with Richard Daintree (later commemorated in Queensland) on a series known as the Sun Pictures of Victoria.