If one is Australian, especially if one loves this country, one will understand anew or more deeply why the people of a young nation came together, across the land, in a fellowship of grief so profound that it became an essential part of what it means to be Australian. It was foolish, we then realise, to condescend to the crudity of the propaganda. Worse, in doing so we offend against its victims. Who can claim with justified confidence that in the clamour of great upheavals they will retain an ear for what rings false.

‘Hold onto your reason’, someone will say. And, of course, we must because, as everyone knows, emotion can cast it aside; can cause us to ignore or deny facts and arguments that are not congenial to beliefs to which we are emotionally committed.

Sentimental art cannot take us to anything that might rightly be called ‘the reality of war’ or to the reality of anything else. When we are moved to believe something by art, or by what someone has said or done, or by a charismatic personality – by anything whose understanding requires thought and feeling to be inseparable – critical reflection must eventually yield to trust that we have been rightly moved. Only a sensibility nourished by attention to what can show up sentimentality and other forms of the false that are intrinsic to the understanding of the heart can justify the trust. Reason cannot – not alone, at any rate. Usually it is not because emotion defeated reason that we affirm beliefs that we regret holding and having acted upon when we become morally clear sighted. It is because we were bereft of a sensibility, educated and disciplined, that would have enabled us to detect the sometimes crude, sometimes sophisticated, sentimentality, pathos and so on in the propaganda that seduced us.

All that fall reminds us that perhaps Australians never mourned so deeply as they did in the later years of the First World War and its aftermath. Because bodies were not returned to their homes for burial, the grief was sometimes bitter and desperate enough to drive people mad. We would now say it was hard for them to reach closure, but the concept of closure is inadequate because nothing can ever fully reconcile us to the death of those we love; nothing can abate the mystery that a human personality has disappeared. The mystery of death is inseparable from our affirmation that human beings are irreplaceable and precious – precious to some particular people, of course, but also precious, period. That, I suspect, rather than fear of death, is the deepest impulse to believe in an afterlife. Nonetheless, though it does so inadequately, the idea of closure gestures towards our need to be able to consent to our grief without resentment or bitterness that would poison our souls.

It is therefore for the sake of dead soldiers that we should remember them truthfully. Jingoistic lies dis-honour them. No one wants to die in cloud-cuckoo-land and no one with self-respect wants to mourn there. Truth is one of the most precious gifts we can offer dead soldiers. It is how we honour the dignity of their humanity.

To trust that truth is never alien to anything precious is, I think, essential to understanding, in our bones, that we are mortal creatures. If, therefore a truthful narrative of our dead soldiers conflicts with comfort for the living, respect for the dead requires that we be truthful and gently turn aside protests that half-truths will allow them to rest in peace. But I am speaking now of truthfulness as it concerns a narrative of war, truthful to soldiers considered as soldiers, not simply as individual human beings whose psychological particularity we must take into account.

Looking at the world with a fearful eye I find it impossible to believe that war is over for us. Deepening political instability in many regions of the earth may cause even more people to be uprooted than were uprooted last century. Strong nations are likely to protect themselves, as we have done, in ways that become increasingly brutal, testing the relevance and the authority of international law. In such circumstances nationalism turns ugly. We see its terrible consequences in history and we see them now in many parts of the world where people are murdered in the name of nationhood.

Good people defend the slaughter because of their national or religious allegiances. True to the same allegiances, others fall silent when they should protest.

The conditions of modern warfare, especially of what we call ‘asymmetrical warfare’, make it harder for us to acknowledge that we share a common humanity with our enemies; demonstrated, for example, when Allied and German soldiers shook hands to establish a truce at Christmas in 1914 so that the dead could be buried; and when Anzac and Turkish forces buried their dead together at Gallipoli. If we are not to sleepwalk to the next war we must determine and then try to create the conditions that enable the humanity of our enemies in war to remain visible to us, even as we fight fiercely knowing that we have no option but to kill them.

Propaganda that radically dehumanises the enemy should be regarded as a crime against humanity because it intentionally destroys those conditions. Sometimes it undermines our capacity even to find intelligible that shooting enemy prisoners or killing women and children of the enemy are crimes.

There is, however, an important challenge to what I have said. It is not doubt that such conditions can be created. It is the belief that they are almost certainly not desirable. When civilians risk their lives for the sake of others, we call them heroes. Soldiers are expected to do it as a matter of course, for their comrades, their nation or for a cause. What can enable them to do that? Can we ask them to be lucid about what it means to go to war; should we encourage denial that death will stalk them? Must we partially dehumanise them so that they can kill? (Many soldiers do not shoot to kill.) Must we dehumanise the enemy so that our soldiers are more ready to kill them? Is it not irresponsible and, indeed stupid, to send soldiers into battle who are psychologically unable to kill without hesitation, to kill before they are killed?

I do not know the answers to these questions. Part of any answer, however, must be that we should, as a sacred national duty, do all in our power to become, individually and as a nation, resistant to the romance of war, to become people who would never joyously go to war, who would go only as a last resort, having honestly exhausted all other possibilities, providing that doing so did not render us incapable of winning when we acknowledge the necessity – the real necessity – to fight. That last qualification registers the fact that nations must sometimes ignore well-intentioned but futile efforts to prevent conflict, by the United Nations for example.

Another part of the answer derives from the imperative to think hard about patriotism, collective guilt and shame, and the place of international law.

Love of country is always a mixture of gratitude, pain, joy, sorrow, pride, shame and sometimes guilt. In the circumstances that make them appropriate, each can be a form of love of country, just as severe criticism of one’s country can be a form of loyalty to it, and the desire to love without shame and without lies is a form of concern for its welfare. The task therefore is not to disparage the very idea of love of country, as some who have been understandably shell-shocked by the murderous consequences of belligerent nationalism do, but to find ways to block the many paths that love finds to jingoism and to open paths on which jingoism can find its way to love.

In Crimes Against Humanity Geoffrey Robertson said that last century saw the acceptance of the idea of international law and that this century would see its increased enforcement. The first part of that is true. It is now impossible for nations

to profess that the pursuit of their national interests should be entirely unconstrained by international law.

The task for the nations of the world is to ensure that the second part of Robertson’s statement becomes true.

Love of country that is clear-sighted acknowledges that other peoples love their countries and that they will fight and die for them, nearly always believing that their cause is just. To try to ensure that the world becomes a community of nations – constituted as a community because each nation freely renders itself answerable to international criminal law – is the best expression of that acknowledgment. Such acknowledgment does not constrain the right of states to pursue their national interests. Rather, it as an enlargement of the concept of the national interest to include the realisation that citizens desire to love their country without the shame that would follow if it were to act in ways that would justly bring it before an international criminal court. That does not mean we should wish to become citizens of the world ruled by a world government. It is best that we remain citizens of particular nations that are part of a community of nations and who find in that community the realisation that all the peoples of the earth share a common humanity. That is one of the ways that jingoism can find its way to love.

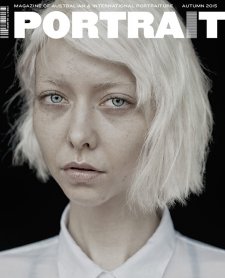

This is an extract from All that fall: Sacrifice, life and loss in the First World War published by the National Portrait Gallery.