Photographs are so familiar to us. There’s a pleasure in taking photographs. Recording our surroundings, our interactions with each other, ourselves, can be an act of sharing, of exploring, of attempting to understand what it is we are looking at. Photographs from childhood, of friends and family viewed as prints in an album or spilling from packets, or viewed as a slideshow on a computer screen, raise up memories. Seeing ourselves as a child merges the image with an imagined memory. That singular picture fills out into a sensory-rich memory echo, prickling with the flush of intense emotions. From decades ago, from last night, a hazy memory takes form. The emotional pulse of yesterday’s feeling still hurts hard.

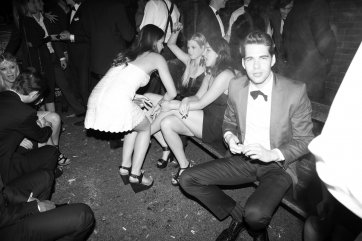

American photographers Larry Clark and Nan Goldin make photographs of such deep sensitivity they see past the bruised souls of those they capture to a glimpse of the purity at heart. For Clark, going back to his home town and taking portraits of the older kids he used to hang out with was a way to validate an adolescence he felt he was denied, that he felt came late. In 1963 in Tulsa Oklahoma, Clark could project his sense of self outward onto the bodies of the boys he wanted to be. In his photographs boys are sure of themselves, boys and girls make out. Clark’s silvery black-and-white prints distil that yearning for inclusion.

Goldin’s portraits of herself, her lovers and friends share the painful honesty of true emotions revealed.

In 1983, in New York City, the morning-after feelings were stripped raw. Her warm-hued colour photographs bring forth the heat of the body and its pulsing blood. Both photographers make portraits to try to understand themselves, those closest to them and those they want to be closest to.

Here’s where feelings swell. For you, for me, for us, looking at photos of our youth, didn’t you know how beautiful you were? Memory holds the self-conscious feelings of adolescence.

How does my body look as it changes?

Who do I long for?

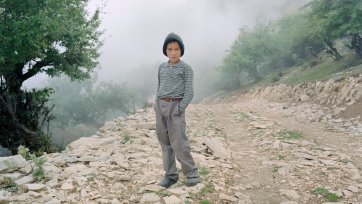

When American photographer Richard Avedon set off on his epic journey to make portraits across America’s vast mid-west, he thought he was going to create a sweeping portrait of a typical kind of America. What he got was a series of portraits that are shockingly unguarded. Avedon’s skill was to convey that moment when self-consciousness is dropped. His portrait of thirteen-year-old Boyd Fortin holding a gutted rattlesnake was the first portrait he took for the series. The kid is an angel, with a cloud of consternation flashing across his face.

Here’s the wet grass and smell of the bush, wearing shorts, warm air, ambient sounds of nature resting and floating around, a calm place. Here’s the routine of swimming every day, the sting of cool water then your body forgetting the cold and recognising the familiar suspended lax gravity of the sea. The expanse of ocean swell and the tilting horizon and rocks and beach. Do you remember the shiver caused by a breeze on your bare skin? A shiver that vibrates the skin like a brush on a snare drum.

American photographer Collier Schorr’s photograph of a pair of college wrestlers is a classic image of athleticised masculine energy, their bodies in tension and torsion. Schorr sees something else too, a sinuous rhythm in their contact like a dance. Here’s a kid with a bloodied nose, another with an ice-pack to his forehead. Here’s an army cadet – a boy on his way to becoming a man. Schorr understands the heaviness of the burden that adulthood imposes on everyone – the expectation of having to choose who it is you are going to be, to define your essential self from the set list of categories, and to be painfully aware of what it might mean to deviate from them.

Many of the portraits selected for this year’s National Photographic Portrait Prize exhibition flicker with complex emotional registers. Outwardly bold, they suggest inner reflection. Surety is based upon serenity. Innocence is deepened by a flash of self-awareness. In the evening air, in space, self-hood is quietly energised.

This year we received a record 2,500 entries. With Angus Trumble, the National Portrait Gallery’s Director, and photographer Nikki Toole, we selected 44 exhibition finalist portraits. While many images showed insight, drama or sensitivity, those that really made us pause conveyed something more. Many of the photographs selected for the exhibition revealed to us something surprising about their subject – we could strongly sense their candour, or trepidation, as they revealed a glimpse of their inner self. All of the exhibition portraits are defined by clarity and a strong or subtle visual composition either in balance or in tension. The strength of these portraits is felt subconsciously. The creation of these photographic portraits – tender, haunting, atmospheric, and honest – is the result of the photographer’s eye.