Sydney artist Matthys Gerber is painting on commission the portraits of three of Australia’s top professional cyclists: Cadel Evans, Stuart O’Grady and Robbie McEwen.

The work, comprising three one-metre square canvasses, can be hung as a large triptych or as individual portraits. Is this a prescient artist being simply considerate of hanging space? Not really, in fact, a portrait of three top cyclists that can be hung either as a group or individually tells us something about the sport of professional cycling.

Over the past ten years, since he first won professional cycling’s great race Le Tour de France in 1999, the story of Lance Armstrong has brought the sport of cycling to the attention of the world outside of Europe. This year Cadel Evans was favourite to win that race and the reason for three weeks in July over half a million Australians eschewed a good night’s sleep in favour of staying up to watch a three and a half thousand kilometre bike race around France.

Bike racing is huge in Europe both in terms of participation and fans. Professional cyclists are revered as sporting heroes and not just in their own country but across the continent. For Australians this might be hard to grasp considering our proclivity to translate the win of any Australian athlete into a win for Australia. Cyclists in Europe race for their sponsor. Perhaps the best example of the sans frontière character of cycling in Europe is the French have not had a home-grown winner of their country’s great annual sporting event for twenty-three years. Their focus has had to be on the overall achievements of teams with French riders regardless of whether a Dutch bank or a Belgian pharmaceutical company puts up the money.

Cadel Evans, Stuart O’Grady and Robbie McEwen all race for European teams and their greatest achievements have also occurred on that continent. Evans has twice been runner up in the Tour de France, O’Grady won cycling’s Wimbledon the prestigious classic, Paris–Roubaix in 2007, and Robbie is a triple winner of the Tour de France’s sprinters green jersey. O’Grady has also won Olympic Gold on the velodrome in Athens, Gold in the Commonwealth Games road race in Manchester and a stage in the 1998 and the 2003 Tours de France. McEwen at eighteen was National BMX Champion and has twice been Australian National Road Race Champion, and before switching to the tarseal, Evans won the Mountain Bike World Cup in 1998 and 1999.

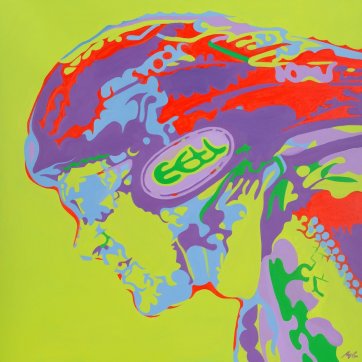

Gerber admits his portrait of Evans, O’Grady and McEwen might be too colourful for some, however, for the subjects themselves jazzy isn’t a problem. Cyclists don’t dream of gold, silver or bronze instead they strive for yellow, green and pink, and if you’re world champion then the rainbow jersey is yours. Not only was Gerber interested in the technicoloured team kits, he was also attracted by the challenge of incorporating the necessary accessories of the sport, the helmets and sunglasses.

Using a photograph from a magazine as his starting point Gerber breaks the image down to basic colours on computer and then exaggerates or blows out the highlights leaving only the darkest tones. The result is a type of topographic map where contour lines join areas of equal tone creating random shapes. Across the terrain that Gerber creates through his technique a colour is selected to connect areas of equal tone. When he talks about how the brush marks and colours interact to create the image, Gerber is reminded Bollywood billboards which use colour to distinguish the good guys from the villains – apparently the bad guys are always orange. Posters of the Beatles and Andy Warhol’s democratisation of celebrities also serve as prompts in his work.

The portraits that Gerber is painting for the National Portrait Gallery commission are not traditional in the sense that he is not attempting to capture the soul of his sitter rather it’s their external identity that interests him. Gerber talks about Howard Arkley’s portrait of Nick Cave in the Gallery’s collection, by way of explaining that his portraits, like Arkley’s, are in a category that is as much about technique as it is about the subject. Gerber believes the genesis of this approach is Warhol portrait of Elvis. Despite having never met Elvis, Warhol still created one of the most popular and recognisable images that contributed significantly to the Elvis legend. So it is no surprise that apart from cursory email contact with Cadel Evans, Gerber hasn’t met or spoken to his subjects. Gerber describes his work as being about the processes of the painter, but adds that in his process he finds parallels to the work of the professional cyclist, believing pace, concentration, technique and a focus on ‘getting it right’ are aspects of painting synonymous with bike racing. In fact, having already painted a fellow artist – George Tjungurrayi, also in the Gallery’s collection – a portrait of a composer or a musician would interest Gerber for the same reasons cyclists do. Ultimately, it is what they do that he relates to more than who they are.

Gerber is a keen follower of cycling and he has also found in the sport the name for his artist-run space – Peloton – a French word for a bunch of cyclists. However, as the Senior Lecture of Painting at the Sydney College of the Arts, he is disparaging of any obsession with sport and suggests that a result of the prominence of sport in our national mythology is Australians only trust winners. Nevertheless, he feels no pressure to idealise these champions, he’ll leave any need for worshipful images up to the Sport Hall of Fame. And doubtless once the Cadel Evans, Stuart O’Grady and Robbie McEwen commission is displayed in the National Portrait Gallery the response that Gerber offers to many of the questions that arise during a discussion of these portraits will ring with resounding truth – I am a painter.