In 2003, when the National Portrait Gallery mounted the exhibition entitled Presence & Absence: Portrait sculpture in Australia we justified our close attention to the medium with the statement that ‘sculpture has always played something of a minor role in Australia’s art traditions, often overlooked in favour of painting.

Presence & Absence was an attempt to outline a history of the sculpted portrait in Australia. Not unexpectedly, almost all of the portrait sculpture assembled in the exhibition conformed to long-established conventions and was mostly in the form of the life-sized, or near life-sized, busts.

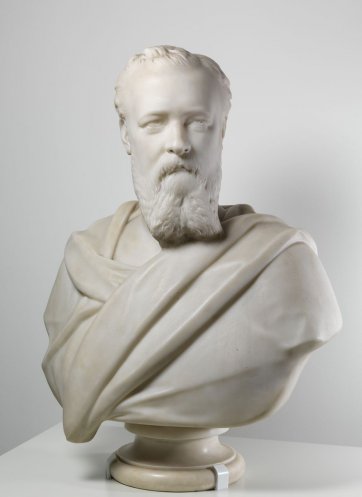

In the new National Portrait Gallery sculpture is emphatically present. Sculpture, because it inhabits space, exists in a close association with architecture and this is the case in the new building. Visitors approaching the Gallery along its western edge will discern an arrangement of busts that forms a coda to the early nineteenth-century display in the Robert Oatley Gallery. On entering the space, you find major works by Australia’s leading sculptors in the genre: Achille Simonetti, Charles Summers and Bertram Mackennal. The nineteenth-century display includes four Summers portraits made in the 1870s which form a kind of micro-portrait gallery in themselves. Each bust represents different facets of success in respective professions – John Fairfax, businessman; Sir John Manners- Sutton, colonial administrator; Rev. Charles Perry, the first Anglican Bishop of Melbourne, and William Wardell, the architect of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Melbourne. These busts date from the period after Summers had left Australia and had set himself up in a highly successful portrait enterprise in Rome.

Summers’ work represents the high points of the sculptor’s craft in the nineteenth century – marble busts and grand public sculpture. Summers’ success with the large-scale Burke and Wills monument notwithstanding, his decision to establish a studio in Rome was a demonstration that the Australian colonies could not be expected to provide a steady stream of sustaining opportunities for sculptors. Thomas Woolner, a well-trained and exhibited British sculptor at the time of his arrival in Australia in 1852, aspired to largescale commissions but had to make do with more modest forms during his two years here. He eventually achieved his aim long after his return to Britain when he secured Australian commissions for the centenary statue of Captain Cook in Sydney’s Hyde Park in 1874 and the bust of Sir Redmond Barry in 1878. During his Australian sojourn Woolner specialised in portrait medallions, not only a form that was readily executed, but also one that lent itself to reproduction. It was affordable art. The National Portrait Gallery collection includes Woolner’s medallions of the hydrographer Phillip Parker King (in plaster) the politician WC Wentworth and governor Charles La Trobe (both in bronze; both existing in numerous versions).

Working on a more modest scale Theresa Walker specialised in making portrait medallions in wax. The National Portrait Gallery owns her medallions of the Governor of South Australia Sir George Grey and his wife, Eliza. For the first display in the new National Portrait Gallery these have been supplemented by her portraits of South Australian Aborigines – Keretamaroo and Mocatta lent by the National Gallery of Australia.

Theresa Walker is often described as Australia’s earliest women sculptor. The National Portrait Gallery display shows that women have been strongly represented in portrait sculpture ever since. The display includes Theodora Cowan’s massive bust of Edmund Barton; Barbara Tribe’s humane portrait of Stanley Bruce; Enid Fleming’s Art Deco busts of Kingsford Smith and Ulm made during their lifetimes; Daphne Mayo’s bronze portrait of Dr Christine Rivett; contemporary racing driver busts by Julie Edgar and Paula Dawson’s bronze and hologram tribute to dancer/ choreographer Graeme Murphy.

Sculpted busts and several full figures are found throughout the new galleries, though as yet there are no life-sized full figures in the collection. Their presence is a nod to the tradition of public statuary on buildings in porticos, in gardens and on street corners, most notably the New South Wales Department of Lands building whose façade is studded with portraits. The National Portrait Gallery is, of course, a public building and an element of urban design, therefore fittingly a site-specific sculpture has been commissioned to stand at the entrance to the building. Faces by contemporary Australian sculptor James Angus will be unveiled towards the end of 2009 and will become, I am sure, associated in the public mind with the National Portrait Gallery experience.

As well as forming a part of the history of the forms of portraiture in the collection galleries, sculpture forms a significant part of the Gallery’s opening exhibition Open Air: Portraits in the landscape. The exhibition, whose aim is to demonstrate different dimensions of ancestral identity in Australia, includes many figurative sculptures made by Indigenous artists. Some of these sculptures have functions within ceremonial contexts associated with funerary rites and mourning. It seems that sculpture is inescapably linked in many cultures with remembrance and the creation of presences that continue to live in the present as reminders or embodiments of past lives.