In the many works by Indigenous artists included in Open Air: Portraits in the landscape, painting about the land is fundamentally concerned with perpetuating understanding of ancestry. In some of the works of non-Indigenous artists in the exhibition, the landscape is occupied by a more recent type of ancestor figure.

There is, of course, a significant difference between the way non-Indigenous Australians might apply the word ancestor to denote a forebear and the Indigenous understanding of ancestral beings who created the law, the land and the order of the world. There are, however, threads in the painting of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists that pick out stories of either family members, or historical figures whose influence persists through generations. These impulses to explore and inscribe personal or national origins are often enacted in places that mean a lot to the non-Indigenous artist – either because he or she has spent a particular period of his or her life there, or because he or she has developed a compelling imaginative attachment to a place, as a result, perhaps, of reading about or travelling through it.

Arthur Boyd, born into a family of several generations of artists, grew up the semi-rural suburb of Murrumbeena on the outskirts of Melbourne. Between the ages of sixteen and twenty, he lived with his grandfather at Rosebud on the Mornington Peninsula. In his teens, he made some frank head-and-shoulders portraits and a number of bright landscapes; he later said that this period, in which he enjoyed ‘pure contact with the landscape’, was his life’s most formative, spiritually and artistically. During the war, when he was stationed in Melbourne, his paintings became darker, and from the mid-1940s onward they lurched with scant respite between the desperate and the apocalyptic. After visiting Central Australia in 1951 Boyd turned to anguished depictions of the conditions of Indigenous people he had seen; in the late 1950s he made his harrowing Bride series.

Arthur Boyd’s father, the potter Merric Boyd, died in September 1959. In December that year Arthur, his wife Yvonne and their children moved to London, where they were to live for the next two decades. In 1968 Boyd returned to Australia and visited the Mornington Peninsula, exploring the area where he had lived with his grandfather. Once he returned to London, Boyd looked at his father’s drawings for the first time in years, and they prompted him to reflect on how much his own creative destiny had been shaped by the older man’s life and art practice.

The visit to his grandfather’s territory and the revisited drawings of his father combined in Arthur Boyd’s imagination to trigger a series of paintings of Merric that he painted in London, from memory. Merric Boyd drawing at Rye 1968–1969 is one of this so-called ‘Potter’ series of works. Boyd remembered the way his father sat drawing or painting, with ‘a particular way of holding his feet straight out, of holding a book on his lap. The boots are characteristic of my father.’ For Andrew Sayers, the ‘Potter’ series packs great emotional power, reaching beyond nostalgia, as the landscape ‘seems to participate in the life of the older artist. Just as the artist is himself in the landscape, in all of these paintings there is an inescapable sense that the specific details of the landscape have been internalised by the artist – a sense heightened by our knowledge that many of these most precisely captured and nuanced landscapes were painted far away from the places they evoke.’

Boyd was not just physically far away from the hazy coastline of the Mornington Peninsula when he made these pictures. At the same time as he was producing them in London in the late 1960s, he was bringing forth his Nebuchadnezzar series, a world away from them in sensibility. For the artist, curator Barry Pearce believes, the series of pictures including Merric Boyd drawing at Rye constituted a necessary aesthetic and imaginative counterpoint, ‘a sanctuary for nostalgia and innocence, something recovered from the rich terrain of his own immediate history’ as he conjured up image after image of the Biblical figure’s horrible debasement. Artist and wife near Arthurs Seat 1969 goes one better, in depicting Arthur Boyd himself in the act of painting his wife, Yvonne. In it, Pearce observes, Boyd replicates his father’s pose in Merric Boyd Drawing at Rye, but he teams the nod to his ancestry with ‘an open homage to the naked beauty of his muse, beneath an open, pellucid sky in which there is no trace of the cloud.’

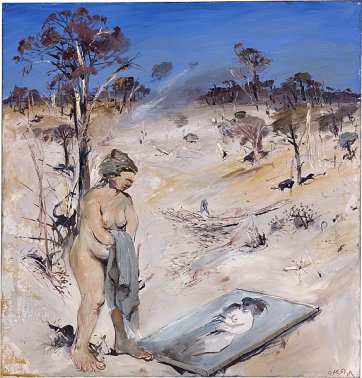

A second selection of works by Arthur Boyd in Open Air depicts Yvonne in the dry surrounds of the Australian Capital Territory. In late September 1971 the Boyds came to Canberra for Arthur to take up the Creative Arts Fellowship at the Australian National University. After the family settled into a house in the new suburb of Garran, the artist began painting in the bush just minutes from the city. In the vivid words of art historian Mary Eagle, in the capital, where ‘a remarkably blue sky rose endlessly above white-grey pastureland on which shadows were etched in black’, the painter ‘responded to the crystalline light’. Boyd told an interviewer that Victoria had been his main inspiration until he went to Canberra, where ‘I could walk into the country in five minutes. It was quite marvellous: there was this undulating, rolling quality. And the weather – the blueness of the sky … the blue is so intense compared to the Victorian.’ Recalling the times when she and Boyd went out into the country, Yvonne Boyd said the large canvases the artist painted in the Canberra landscape were the first of the ‘blond landscapes with blue skies. He liked the way the ground was lighter than the brilliant sky. There was some wonderfully clear weather. The summer sun was fierce … The days when I posed nude for Arthur were the blue days.’

Over the course of his career, Boyd produced the most anguished body of work of any Australian artist, repeatedly depicting cripples, persecuted lovers, ravaged women, humiliated men and tortured animals. But in the small corpus of paintings such as those exhibited in Open Air, Darleen Bungey suggests, Arthur presents Yvonne Boyd as ‘a vital ingredient of the day.’ She observes that this is ‘the only time that a full-blooded, naked woman has entered any of Arthur’s paintings stripped of myth, allegory, tension, despair, angst, frustration, burden. She is out in the open, on her own terms … Now, after almost thirty years, the viewer exhales.’

As the spring of 1971 moved toward summer the Boyds went on weekend trips away with academic friends such as Valerie and Peter Herbst, Rosemary and Bob Brissenden and Dymphna and Manning Clark. The portrait of Manning Clark with Tuppence, the Clark family dog, in the scrub at Wapengo south of Bermagui on the New South Wales coast dates from this period. Bungey finds the painting ‘so still, so expectant, we can almost hear through the stillness a faint scuttling, a crackling’. Dymphna Clark, apparently, could not look at the portrait without sensing a malevolent presence lurking about her husband. But Boyd thought Clark ‘a beautiful person … very delicate’ with a ‘very gentle Christ like approach to life’, and most people, especially those unfamiliar with either Boyd’s demons or Clark’s, would see the direct and simple painting, completed in an afternoon, as one of Boyd’s most poignant portraits. Above the artist’s signature and the painting’s date are inscribed the words of friendship, ‘for Manning’.

The Boyds stayed in Canberra until late February 1972. Mary Eagle says that Boyd ‘jumped a groove’ in the city: ‘You don’t mean to break out, but when you do you can delude yourself into thinking the next thing will be better,’ he said. Indeed, the stay that produced these lovely pictures of Yvonne out in the open also gave rise to the Caged painter series, painted in London, of the frustrated artist in a variety of anguished situations with rabbits, rams, dogs, chains, wire, syringes and boiling billies, the blinding brightness of the Monaro punching through their darkness. Yet also after Boyd had returned to England, he made another Port Phillip painting, of his old friend and fellow artist John Perceval, who had taken up the first Creative Arts Fellowship at the Australian National University in 1965. Boyd made scores of landscapes after he returned to Australia to live in the Shoalhaven area in the early 1980s. Very seldom, however, did he again paint a complacent figure in the landscape such as those exhibited in Open Air.

Boyd’s great contemporary, Sidney Nolan, grew up in Melbourne, and as a young man he spent time in the white Wimmera landscape of north-west Victoria and at Heide, near the Yarra at Heidelberg. Between 1945 and 1947 he created his first major series as a mature painter – the Ned Kelly series – as meditations around ‘a story arising in the bush and ending in the bush’. Andrew Sayers, who wrote the catalogue accompanying the exhibition of the Kelly works at New York’s Metropolitan Museum in 1994, has observed that Nolan sensed that there was a way in which the landscape is defined by the stories that happen within it, and which ‘persist in the memory’. Nolan’s interest in the Kelly story took him to the ‘Kelly country’ of northern Victoria; yet in this series of paintings he distils some of the sense of space and light he had experienced in other parts of Australia, and which he discovered in photographs – such as those he found in the pages of the Australian travel magazine Walkabout.

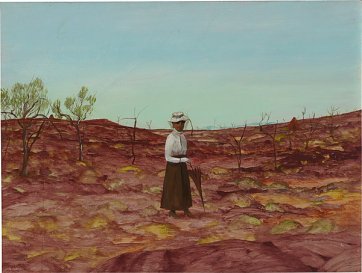

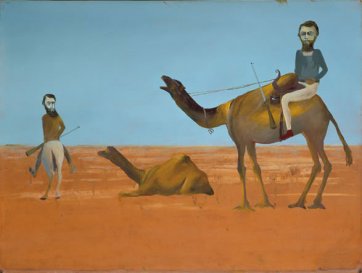

Ned Kelly’s short-lived battle with authority was only the first instance of Nolan’s interest in the conjunction of Australian stories and specific landscapes. During the second half of the 1940s he went on to paint other place-based stories, notably of the heroic Mrs Fraser (shipwrecked on the island later named after her). In 1949, when he was in his early thirties, Nolan first saw the desert from an aeroplane, and soon after he travelled through it on the ground with his first wife, Cynthia. Seeing the continent’s ‘ghastly blank’ from these perspectives effected a change in the way Nolan understood himself as an Australian and an artist. ‘I doubt that I shall ever forget my emotions when first flying over Central Australia,’ he wrote, ‘realizing how much we painters and poets owe to our predecessors the explorers, with their frail bodies and superb willpower.’ Nolan’s trips to the desert gave rise to a series of void aerial-perspective Central Australian landscapes, which were shown at the David Jones Gallery in 1950. Alongside these, however, he made a number of desert scenes incorporating European figures, the first being Burke and Wills Expedition 1948. He was to return to the theme of the explorers in the mid-1980s. The three paintings of Burke and Wills in Open Air, together with the stark depiction of Daisy Bates at Ooldea, span the years 1948 to 1961.

In exploring the story of Burke and Wills, Sayers writes, Nolan began with the narrative and dipped into the large archive of visual material that had been created in the early 1860s at the time of the expedition. It was the first great public event in Australian history to be extensively recorded in photographs, drawings and prints, and in the popular press, but such raw material was simply a cue for Nolan’s imaginative drawing together of the story and of his own visual exploration of the Australian landscape.

Nolan’s first series of Burke and Wills paintings suggests a disjunction between the figures of the explorers (with their camels and horses) and the landscapes through which they moved. In Burke and Wills expedition 1948, for example, the figures appear as collage elements stuck onto the landscape, like the hard-edged figure of Ned Kelly in many paintings of the series that had come before. The scrapbooking mood is evoked, too in Daisy Bates 1950, painted in Sydney after Nolan and Cynthia had visited Ooldea. While the glued-on effect was part of Nolan’s artistic strategy in the 1940s, to create landscape space, the effect of both of these pictures is to emphasise the foreignness of the figures in the landscape; they are ridiculous, poignantly puppetlike in their tiny uprightness. Yet once the artist returned to the series of Burke and Wills, and his appreciation of the scale and ramifications of their non-achievement intensified, a subtle transformation took place. By the 1960s man and camel became fused in the seamless treatment of the material of their construction. The figures are apparitions, ghost-like in a landscape of mirages – man and nature finding themselves together at the Gulf of Carpentaria, in a place where water and earth meet in a shifting, indivisible mix.

The dates of the works from the Burke and Wills series in Open Air are confusing, but puzzlement on the part of the viewer will not be resolved by consulting the dates of works in the series as a whole. Although Nolan painted many phases or episodes of the expedition of exploration, he neither painted them in the order in which they occurred, nor aimed to produce an accurate historical record of the trip. Burke and Wills leaving Melbourne 1950, a lonely and empty representation of what was, in fact, a tumultuous public departure, comes after Perished 1949, showing Burke moribund or dead. Burke and Wills at the Gulf 1961 shows the explorers in the water of the Gulf of Carpentaria, notwithstanding that Burke recorded that they ‘could not obtain a view of the open ocean, though [they] made every endeavour to do so’. By contrast, Perished reflects what has long been accepted as a terrible truth. Following the disintegration of the expedition, when Burke, Wills and King were starving, Burke and King left Wills in camp while they went to try to find Aboriginal people who would help them obtain food. According to King’s account, Burke collapsed, and knowing he was dying, told his companion not to try to bury him, but to leave his body on the desert ground, his pistol in his hand. Perished shows Burke’s body flatly conforming to the undulations of the dusty soil; he is drained of life, his feet slack paddles, his face rock-like and his beard a tangle of desiccated roots. In Perished the man is in the process of becoming a part of the landscape he set out to explore; already the vegetation is taking over.

In theory, the figures in Perished and Burke and Wills at the Gulf should look less alienated than those in their ‘cutout’ counterparts. Still, however, there is a sense of emotional distance about them, for which various critics have attempted to account in different ways. Kenneth Clark wrote that ‘there is in nearly all Nolan’s work a preference for the insubstantial … His pictures levitate … his dehydrated horses are so light that a man can pick one up.’ Nolan, however, responded that ‘These are considered rare qualities by the Chinese … Even when I was young, I had this feeling of transience.’ James Gleeson suggested that when Nolan looked at something it was ‘as though he had no memory of ever having looked at such a thing before. He notices startling and beautiful relationships because he is not predisposed to interpret his visual experience in any particular way. The very nature of Nolan’s particular genius precludes an introspective or meditative quality.’ Although these paintings depict both jubilant and desperate stations of a tragedy, they are serene, impassive as the landscape and of history itself.

Nolan’s body of work has contributed directly to how Australians see and sense the country that surrounds and shapes them. But it is also a progenitor of influence. At Nolan’s suggestion, Alan Moorehead wrote the book Cooper’s Creek, a compelling factual account of the Victorian Exploring Expedition published in 1963 with Burke and Wills expedition 1948 as the cover image. Nolan’s desert paintings of the late 1940s triggered a novel that had for some years lain dormant in Patrick White: Voss, which was one of the novels for which the author won the Nobel Prize for ‘an epic and psychological narrative art which has introduced a new continent into literature’. Further, Nolan’s Kelly series, exhibited in Melbourne in 1962, sowed the seed of True History of the Kelly Gang in the mind of Peter Carey, who recalled in an interview in 2001 that this, the second art exhibition he had been to in his life, ‘just burned into my brain, forever’. Each of these novels, in turn, further embedded the relationship to country in the imagination of several generations of Australians.