In the months leading up to the opening of its dedicated building the National Portrait Gallery acquired two separate gifts of portraits by Sir William Dobell (1899-1970).

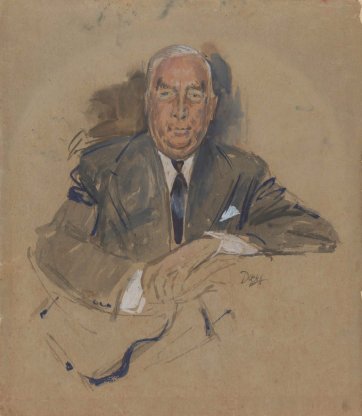

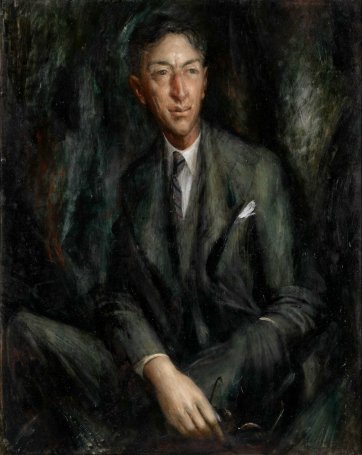

Painted within a year of each other in 1950 and 1951, Dobell’s portraits of Sir Charles Lloyd Jones and Sir Hudson Fysh date from the period of the artist’s return to portraiture after the scarifying fallout from his portrait of Joshua Smith in 1943.

Sir Charles Lloyd Jones (1878-1958) was born in Burwood and grew up in Sydney, where he studied at Julian Ashton’s art school in 1895. Showing little promise as an artist, he qualified as a tailor and cutter in London before marrying for the first time. His grandfather was David Jones, and he began work in the David Jones clothing factory in 1902. By 1905, he was the store’s advertising manager; he became a director in 1906, when David Jones Limited became a public company. Together with Sydney Ure Smith and Bertram Stevens, he founded the pioneering art and lifestyle magazines Art in Australia and The Home at the end of the First World War. In 1920, he embarked on his nearly four decades as chairman of David Jones Limited, which gradually expanded in Sydney and then across the country.

Charles Lloyd Jones took a keen interest in music and the visual arts, and amongst many other public positions he adopted as his career progressed was the first chairmanship of the Australian Broadcasting Commission, in 1932. That year, as a member of the Board of Control of the Australian National Travel Association – then three years old and under the chairmanship of Harold Clapp – Jones gave a lecture on ‘Selling Australia to the World’ to students of Blennerhassett’s Commercial Education Society. Jones explained that overseas, until a few years previously, Australia was either unknown ‘or known only by its misfortunes, strikes and other regrettable instances’. Suggesting that one day, tourism in Australia could rival the wool trade in importance, he pointed out that he was ‘very often told that if the Americans had a beach like Bondi or Manly or any of our famous beaches the whole world would know about it. Everybody has heard of Wai-Ki-Ki but nobody has heard of Bondi Beach. We have got some wonderful things to sell the world.’ To encourage international visitors, who promised a source of substantial and uncomplicated income, the Travel Association arranged for the production and overseas distribution of posters and booklets showing the country’s scenery, flora and fauna. In addition, they produced a booklet, ‘Talking Points’, available to any Australian travelling abroad, suggesting conversational gambits ‘which we feel will make him a good representative for us’. Interestingly, Jones emphasised that ‘those travellers who come here with their money will not only bring their material wealth but help to educate us with ideas for the advancement and development of this country’.

A generation younger than Jones, Sir Hudson Fysh KBE DFC (1895-1974) was one of Australia’s great aviation administrators. Born in Launceston, Tasmania, he enlisted at the beginning of the First World War and served on Gallipoli before joining the Australian Flying Corps as an observer and winning the Distinguished Flying Cross. In 1919 he qualified as a pilot. Later that year he was commissioned by the Australian government to survey the Darwin to Longreach section of the Britain– Australia Air Race, which lack of funds had prevented him from entering. In November 1920 Fysh and Pat McGinnis, who had driven with him on the survey, joined several others to form Queensland and Northern Territory Air Services Limited. Fysh became managing director of the company in 1923, but continued to work as a pilot over the next seven years as QANTAS established various routes and functions – including an air ambulance service – in Queensland. In the early years of his marriage, he and his wife lived in Longreach; it was there, during a storm, that he witnessed the freak phenomenon of fish falling from the sky and flipping around in the streets (he contrived to keep a few alive in a water tank for a few days). In 1934, in partnership with Imperial Airways, QANTAS began to operate the Singapore–Australia air route, trading as Qantas Empire Airways. Six years later Fysh became a director of Tasman Empire Airways Ltd, which flew to and from New Zealand.

Charles Lloyd Jones was a trustee of the National Gallery of New South Wales from 1934 to 1958 (in which year it became the Art Gallery of New South Wales). In the early years of this period, in 1939, William Dobell returned to Sydney after a decade abroad. He had taken the steps necessary for any jejune Australian artist to metamorphose into a credible practitioner: he had travelled widely in Europe looking at art, and had exhibited at London’s Royal Academy. Sure enough, as soon as he arrived home his experience and demonstrated artistic influences managed to impress adherents to conservative and modernist art factions alike. In his first year back, the National Gallery of New South Wales bought his Boy at the Basin 1932; over the next few years the Gallery purchased several more of the paintings he had made in London, including The speakers, Hyde Park 1934, Mrs South Kensington 1937 and Street Scene, Pimlico 1937. By 1944 Dobell was made a Trustee of the National Art Gallery himself.

As prominent Australian businessmen, through the 1930s, 1940s and beyond both Fysh and Jones were called upon to state their observations about where the world was heading and possible future roles for Australia. Because of his line of work, Fysh, in particular, was widely travelled. In early 1939 he conveyed his ‘Impressions of a Trip Abroad’ to members of Sydney’s Millions Club. Naturally, he spoke specifically about developments in aviation (‘we must remember that nothing ever built for aviation yet was half big enough for more than a very short time’). Also, though, he described how he had seen ‘great crowds of Jews clamouring for passports’ at the British embassy in Berlin. ‘With typical German thoroughness and ruthlessness the country is unloading its Jews onto the world,’ he reported. ‘[A]ll else which she thinks stands in her way will be swept aside unless might is met by might and the Democracies marshal their forces in a truly convincing fashion’. Having lovingly described a Christmas dinner he had enjoyed in an English country house, he concluded by stating that there were tough times coming, but ‘our heritage is amply worth defending’. Similarly, in 1958, in the midst of a critical period of the Cold War, Fysh wrote an engaging booklet about what he had seen on a trip to Russia. ‘The bath, supplied with really hot water, was almost big enough to dive into – most luxurious – but without a bath plug. This deficiency one tried to overcome by keeping one’s foot over the drain hole.’ Fysh admitted to becoming obsessed with the question of where all the Russian plugs had got to: ‘Our hand basin had no plug, neither did the basin of the latest Russian aircraft’. He described seeing ingenious portable toilets on a lorry, and the absence of not only dogs (of which the only specimen he saw was the British Ambassador’s) but advertisements: ‘No where could one see the rival claims expressively set out as to whose toothpaste was the best. Presumably in Russia there is a State toothpaste.’ At a visionary level, however, the pioneer of air travel stressed that: ‘We can recognise that the peoples of the world cannot continue to live in sealed off segments … Using aircraft now on the drawing board, it will be possible to fly from Australia to Russia in under four hours. It seems certain that the intense development of world travel which is taking place will have a profound effect on international relations and must form a valuable medium for peace, travel being one of the world’s major businesses in which each nation depends on the other.’

During the Second World War Dobell served in the Civil Construction Corps and in a camouflage unit, alongside his fellow artist Joshua Smith. Great figurative works including The Cypriot 1940 and The Billy Boy 1943 arose from this experience. However, the war years ended in personal anguish for Dobell in a way that he could not have foreseen. In January 1944 Dobell’s portrait of Joshua Smith was awarded the Archibald Prize for 1943. Disgruntled, two other Archibald entrants alleged that Dobell’s work was a caricature of his friend, and the most famous court case in the history of Australian art ensued. Notwithstanding that the prosecution called a doctor as a witness, who stated in some detail his opinion that the painting represented a corpse well on the way to decomposition, the court found that it was a ‘good likeness’ of Smith. The whole affair was mortifying for both Dobell and Smith (although the publicity it generated brought 53 382 people to the Dobell exhibition at the new David Jones Gallery, established by Charles Lloyd Jones in 1944). Happily, the following year Smith rallied to win the Archibald himself. Dobell fell into profound nervous prostration after the case, retreating in 1945 to live at Wangi Wangi on the shores of Lake Macquarie, but he, too, returned to the artistic fray and won both the Archibald and the Wynne Prize in 1948.

Dobell’s portrait of Fysh coincided with the thirtieth anniversary of QANTAS in 1950. The portrait was to be a gift to Fysh from employees of Qantas Empire Airways Ltd; Dobell was commissioned at the suggestion of Fysh’s fellow aviator, Scotty Allan, one of the subjects of Dobell’s great wartime series of portraits. Though he was honoured to be painted by Dobell, whose work he greatly admired, Fysh knew that he never flattered his subjects, and indeed, he writes, he was to become ‘another Dobell victim’. Enervated after a heavy day’s work, he sat for the artist in his small studio in King’s Cross with the late-afternoon summer sun streaming in. ‘Bill gave me two whiskies. I always wore glasses but was induced to take them off to be painted. This produced an inevitable squint. The finished portrait could well have been entitled Man Without Glasses,’ he recalled. Though he and his wife liked it, Fysh described the painting as ‘rather a shock to some people’ when it was unveiled at a function at the Wentworth Hotel, part of the newly formed hotel company Qantas Wentworth Holdings. It was, he said, ‘a magnificent piece of work of a great master, but the treatment of the face … made me look so dissipated and haggard as to cause me to remark that if someone in fifty years’ time were told that the subject was a founder of the great airline QANTAS, he would refuse to believe it.’ (The National Portrait Gallery’s photograph of Fysh, taken by Max Dupain at around the same time the portrait was made, affords a point of comparison with the painting.) The picture of Fysh was entered in the Archibald Prize at the end of 1950, and there was general public agreement that it was the standout for the year, but Dobell was pipped for the prize by William Dargie. In the view of the Bulletin reviewer, the representation of Fysh ‘is ugly. But yet it is alive. There is something genuinely memorable in the negligent ease of the portrait, with so much alert vitality, both of sitter and painter, underlying the surface of polite humour.’ One of Fysh’s sisters saw in it ‘all the evils of our ancestors’ and threatened to slash it; however, hanging in his home, the portrait seemed to the subject to reflect his appearance more and more as he grew older.

In 1949 and 1950 Dobell visited the Territory of Papua and New Guinea, in which QANTAS had been crucially active during the war. The art historian Mary Eagle judges the small works Dobell made in New Guinea to be a high point of his late output. Hudson Fysh, too, admired the exquisite miniatures he made there, and in his own trips to the fascinating region he was reminded, on encountering certain scenes, of works of the artist’s. Once again, however, Dobell was dispirited by public criticism of this body of work and after painting New Guinean subjects for some five years, he relinquished them and returned to portraiture, his subjects including Dame Mary Gilmore and Helena Rubinstein. He won the Archibald again in 1959, and Time commissioned his portrait of Robert Menzies for its cover in 1960. His knighthood came in 1966.

Hudson Fysh oversaw further expansion of QEA, and its purchase by the Australian government, before retiring as the company’s managing director in 1955 and chairman in 1966. Knighted in 1953, between 1965 and 1973 he published three autobiographical volumes covering the history of QANTAS; a biography of his grandfather, Henry Reed, a key figure in the early development of Launceston; and a book on fishing, Round the Bend in the Stream, its lyrical descriptions of fishing, friends and flora in the Monaro region still a trove for local anglers.

Charles Lloyd Jones persisted with his own painting, and exhibited often with the Society of Artists, of which he was treasurer from time to time; he is represented in the Art Gallery of New South Wales and the National Gallery of Victoria. At the same time, he built up a very significant collection of paintings by other artists. He lived at Rosemount in Ocean Street, Woollahra, and was a genial member of several clubs. Dobell painted him the year he was knighted, during the six-year period in which he was commodore of the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron (by the time he took up the position, in 1949, he had been sailing out of the Squadron for forty-six years). Jones’s close friend, Sir Robert Menzies, gave his funeral oration.

These two paintings – one donated by the Australian War Memorial in association with the Fysh family and one part of a group of portraits generously given by the Simpson family in memory of Caroline Simpson – add significantly to the National Portrait Gallery’s collection of works by pre-eminent Australian artists of the twentieth century, as well as to its representations of urbane and visionary Australian business figures. Both the portraits will be hung in the Fairfax Gallery at the time of the opening of the new National Portrait Gallery, as will the portrait of Menzies Dobell completed in just two weeks for Time magazine (on loan from the Art Gallery of New South Wales) and the watercolour sketch for the latter, purchased by the National Portrait Gallery with funds provided by Gordon Darling in 1999.