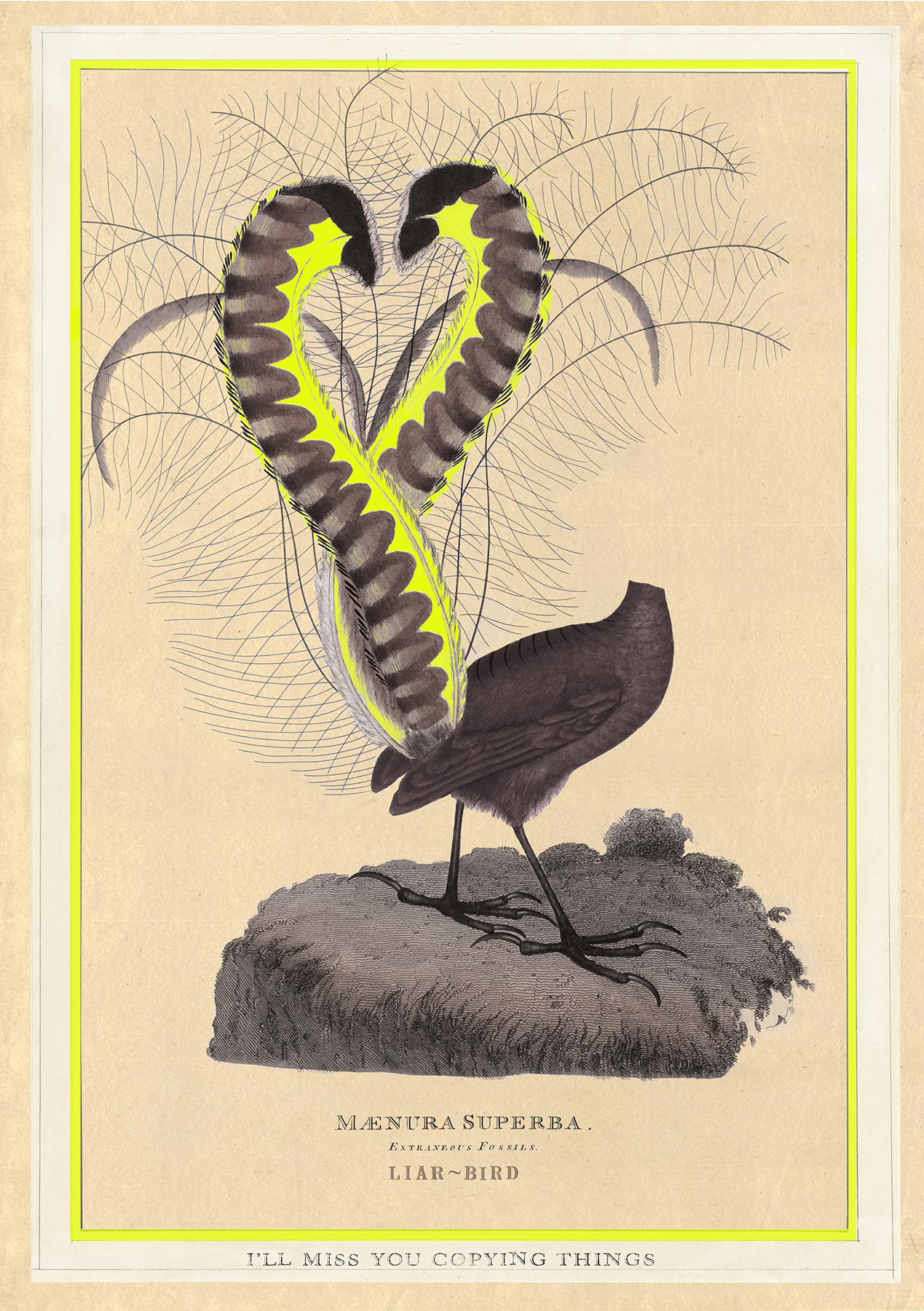

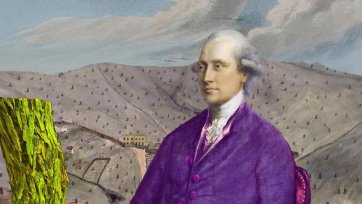

I’ll miss you copying things, 2018 Joan Ross. Courtesy the artist and N.Smith Gallery. © Joan Ross

In the work of Joan Ross we encounter the rich, sometimes weird, and often unexpected textures of an artistic practice that probes the enduring consequences of colonisation, climate change and consumerism with wit and a deft flexibility across histories. This year the artist is working with the National Portrait Gallery on a collaborative project that continues her deep interrogation of the legacies and lies that dwell within the archives of history, situating her work in dialogue with the Gallery’s collection.

Ross is an artist who works in the language of images in preference to words. She describes her process as deeply intuitive with a strong conceptual understanding, and it is often only on later interrogation that the punch of a work is felt. Her use of fluorescent yellow is a visual response to the creep of hi-vis into the everyday environment, the colour used to alert us to the dangers of unquestioned authority. As the fluoro uniform was more frequently donned by construction and security workers following the September 11 attacks, Ross told Byron Arts Magazine in 2016 that she noticed ‘you could do anything you wanted to the land whilst you were wearing it, without being questioned. I began to use it as a metaphor for colonisation as I saw it beginning to colonise my environment’.

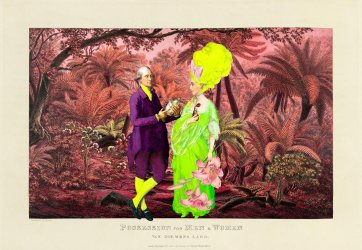

Artists such as John Glover and Joseph Lycett formed a persistent representation of the colonial project that took root in the late 18th century and remains ongoing today. In an art-historical sleight of hand, Ross integrates and repurposes their depictions of the land, treating their work as source material that can itself be laid claim to, and intervened upon, to create new compositions. These borrowed landscapes are often dominated by her insertion of looming privileged figures plucked from the portraits of yet another artist, the 18th-century British Royal Academician Thomas Gainsborough. Across her practice these figures enact the colonial gaze – wanting, taking, claiming. In Ross’ M’Lady Ikebana (2015), Gainsborough’s Honourable Mrs Graham, now dressed in fluorescent yellow and sporting flamboyant ostrich plumes, engages in ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arrangement. As Ross noted in Look magazine in 2018, she used this traditional practice to recast the imposed structuring and control over nature as ‘an act of total disrespect and disregard, which is how I see the impact of colonialism’. Ignorant of the small figures of pakana (lutruwita/Tasmanian First Nations people) that become part of her display, the colonial lady arranges the stems of eucalypts – stripped out from Glover’s Natives on the Ouse River, Van Diemen’s Land (1838) – into vases. Here is a landscape tamed.

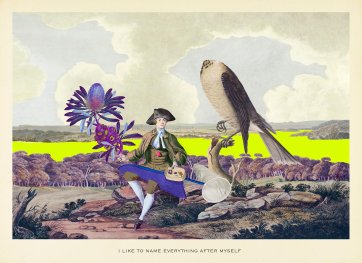

1 I like to name everything after myself, 2021. Collection of Bernard Ryan and Michael Rowe, Singapore, courtesy of N.Smith Gallery, Gadigal Country / Sydney. 2 View of Manly. Land of the tame, 2021. Courtesy of the artist. Both Joan Ross.

In works such as I like to name everything after myself and View of Manly, land of the tame (both 2021), Ross performs a nimble ‘cut and paste’ of various topographies drawn from Lycett’s Views in Australia or New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land (1825). In quoting the work of Glover and Lycett, Ross retrieves these artifacts of Empire, unsettling the statements of possession and plenty they represent. ‘One of the reasons I make the work I do is that I don’t think you can be anywhere in Australia and not be aware that we’re on Indigenous land,’ Ross says. ‘And I’m constantly alert to colonial influence, and the disjunction between that and nature.’

1 Possession for men & women - Van Diemens Land, 2024. Courtesy of the artist. 2 I have your cake and now I’m eating it too , 2014. Courtesy the artist and N.Smith Gallery. © Joan Ross. Both Joan Ross.

The headless bird is a key motif for the artist. In I’ll miss you copying things (2018) Ross has beheaded a ‘liar-bird’ drawn from an engraving of the Superb Lyrebird that appeared in David Collins’ An account of the English colony in New South Wales from its first settlement in January 1788 to August 1801 (1804). Ross sees birds, part of this vast continent’s ancient flora and fauna, as atavistic beings whose song carries the histories of connection and custodianship practiced by First Nations peoples since time immemorial. Ross asks us to consider what will happen to birds in a future beset by climate change, the beauty of this land destroyed. When birds no longer sing.

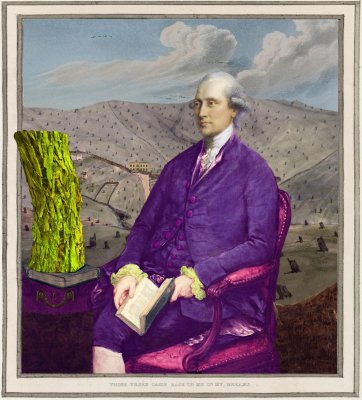

1 You were my biggest regret: diary entry 1806, 2022. Courtesy of the artist. 2 Those trees came back to me in my dreams, 2024. Collection of N.Smith, Gadigal Country / Sydney. Both Joan Ross.

Ross assumes the persona of the colonial woman in her self portrait You were my biggest regret: diary entry 1806, a 2022 Archibald Prize finalist. Embracing a log cut from a native tree with fluorescent yellow gloved hands, the figure is laid over a landscape referencing a view of Castle Hill Government Farm painted around 1806 by an unknown artist. The scene was intended to denote progress. And yet, the dark stumps of trees mark the violent intrusion and ongoing burden of Empire. In her artist statement Ross wrote: ‘There is regret in my eyes as I look back through time, thinking about the damage caused through colonisation … She sees, and we see, that she is a part of it, part of the greed and all the sadness and destruction colonisation has caused.’