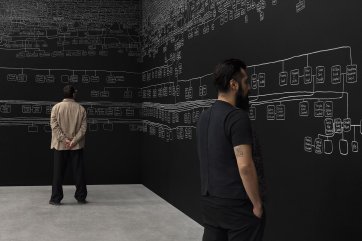

First Nations Peoples of Australia are among the oldest continuous living cultures and one of the most incarcerated, as evidenced in kith and kin by Archie Moore. After viewers’ eyes have adjusted to the low light levels in the Australia Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, an immense genealogical chart hand drawn in white chalk on the black walls and ceiling comes into view. It inscribes the artist’s relations from the Kamilaroi and Bigambul Nations over 65,000 years and more recently his paternal British and Scottish relations. The vast drawing traces the artist’s personal history from himself, close kin, distant relatives, segueing through racist slurs, and extending to countless generations of Ancestors. Anthropologist Norman Tindale’s genealogical diagram that professed to document Archie’s Aboriginal relations is exceeded by the greater complexity of First Nations kinship systems. In kith and kin, the linear chart concerned with the transfer of property transforms into an undulating web of connection that reinforces responsibilities to all living things. Kinship is the organising principle for Indigenous social relations, and incorporates plants, animals, land and waterways. Archie’s drawing reaches so far into time that it captures the common Ancestors of all humans, a timely reminder that every person on the planet has kinship duties to one another.

kith and kin

by Ellie Buttrose, 22 July 2024

In school, Archie was taught that Australia’s history started with British colonisation in 1770, founded on the principle of terra nullius (land belonging to no one), without reference to the First Peoples who cared for the continent for millennia. The artist’s choice of materials for this celestial map of names – fragile chalk on blackboard – invokes the transmission of knowledge and how what is taught within, and what is left out of, the prevailing education system reverberates into the future with consequence. This is not the first time Archie has used the medium of chalk and blackboard. The 2002 series Words I learnt from the English class is comprised of a series of white words written in chalk onto black canvases including racist, sexist and homophobic slurs heard in the classroom. The artwork points to how a discriminatory attitude is something that is taught rather than inherent. kith and kin includes racist terms to teach a similar lesson. The slurs in the later work are terms that Archie found in government, anthropological, church and personal archives when he was searching for references to his family members. The inclusion of terms such as ‘full blood’ and ‘half caste’ points to how people’s humanity is removed when they are abstracted into racial categories. These terms become a boundary line in the composition between the European names of his British, Scottish, Kamilaroi and Bigambul antecedents at eye level and the vast number of Aboriginal names that fill the upper walls and ceiling.

Most of the densely written words that appear high on the wall and the ceiling are comprised of Ancestors’ names. Some are traceable within the written archive, while other designations are speculative propositions by the artist in recognition of the gaps in the written records or oral cultures. At different points across the mural, the artist has used Gamilaraay (the language of the Kamilaroi Nation) and Bigambul kinship terms such as waabi (mother’s mother) or tamar (woman). The inclusion of Archie’s Ancestors’ languages enacts Indigenous language maintenance. Following British invasion First Nations peoples were not only killed off and dispossessed of their land but were also often banned from speaking their native tongue. It is difficult to express the violence that the suppression of language had on Australia’s First Peoples, on their relationships and on their cultures. Archie is a product of this history; both his Kamilaroi and Bigambul grandparents were separated from their lands and his mother had little knowledge of their traditional languages to pass on to her son. While Archie recalls some Gamilaraay words used by family members during his childhood, his primary engagement with the language has been through dictionaries and history books. Placing words such as baaman-di (my father’s sister, Gamilaraay) and kagul (baby, Bigambul) into circulation is both an acknowledgement of what has been lost by his family, and a way to imprint these words on the present so that they can re-enter common usage.

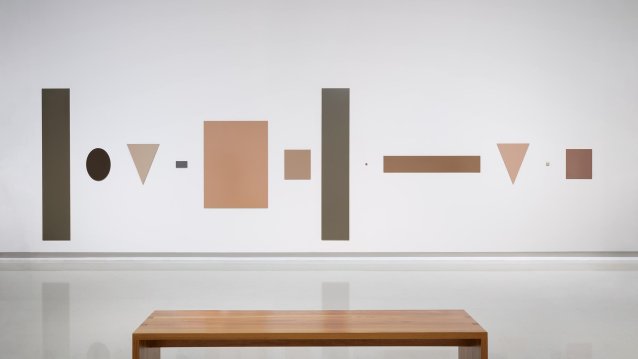

Archie has used his Ancestral languages in other artworks such as Mīal (2022), in the National Portrait Gallery collection. Comprising 34 monochromes that abstractly refer to different parts of the artist’s body, the work is titled Mīal, a Bigambul word which translates into English as ‘Aboriginal man’. Archie named the individual paintings with as many Gamilaraay and Bigambul terms for the corresponding body parts as he could find, such as Walarr (Left) (Gamilaraay for ‘shoulder’) and Bou-you (Right) (Bigambul for ‘leg’). In some instances, Archie points to how these neighbouring languages converge with the inclusion of mara (palm) and mūru (nose) or bin-na (ear). By using these terms in his artwork titles, Archie proliferates the number of mouths annunciating Gamilaraay and Bigambul words beyond those who speak these languages to broader gallery audiences. Returning to kith and kin, the blackboard is a device that is paired with oral learning: the teacher explains ideas verbally, sometimes incorporating a back-and-forth dialogue with students, and then reinforces the ideas through the written word. Archie offers a language lesson that viewers participate in through speaking the names as they walk around the artwork and recount them to friends and family once they have left the pavilion.

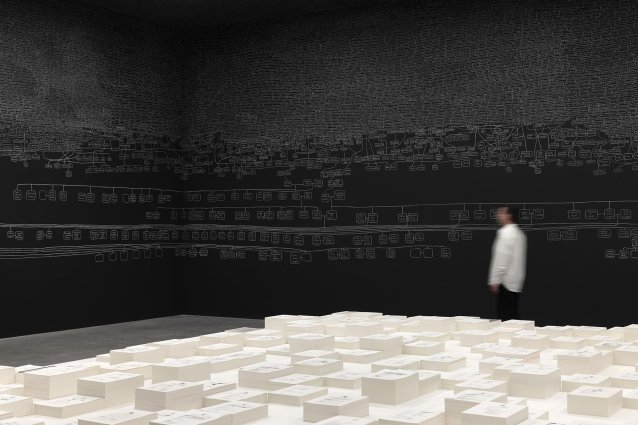

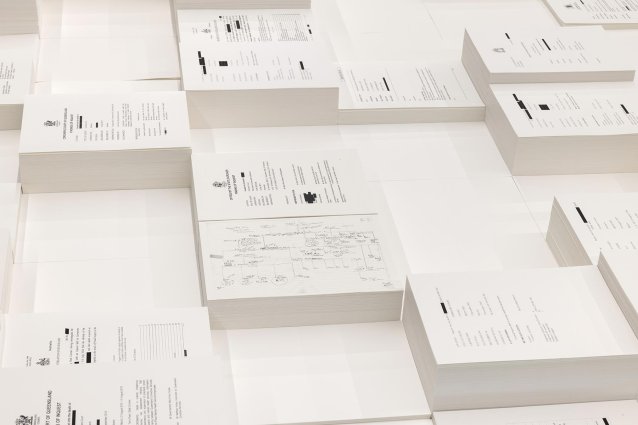

Holes occur throughout the family tree in kith and kin, these absences signalling the severing of familial ties. Another black void occupies the centre of the pavilion. This reflective pool is a memorial for the First Nations individuals who have perished in police custody since 1991. Indigenous Australians are one of the most incarcerated people globally; according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics they comprise 3.8 per cent of the Australian population yet are 33 per cent of prison inmates. Above the water hover stacks of coronial inquests that date back to the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody 1987–1991. Appointed by the Australian Government, it found that self-determination and addressing health, schooling, employment and housing inequality would contribute to a lower incarceration rate. More than 30 years later, many of its recommendations have yet to be implemented, and deaths continue unabated. The volume of coronial inquests makes visible the vast scale of this preventable horror.

By placing this publicly available information at arm’s length Archie articulates the gap between knowledge and action. Names have been redacted out of respect for the deceased. Reports that are not accessible are represented with a blank ream of paper, with these white voids expressing breaches in the record. The administrative reports are cradled by the reflection of the family tree in the water below, commemorating that each of the deceased belongs to this expansive web of relations.

Archie has often used doctrinal documents in his artworks to point to how institutions have failed First Nations peoples. In the sculptural series On a Mission from God (2012), Archie delicately folded miniature bibles into the shape of churches situated on Queensland reserves where Indigenous people were forcibly relocated. Archie chose the biblical page that reproduced Luke 12:47: ‘The servant who knows what his master wants him to do, but does not get himself ready and do it, will be punished with a heavy whipping’ in reference to the punitive conditions First Nations peoples endured in the church-administered missions. In kith and kin, Archie clearly shows how the learnings of the past are yet to be implemented in the present. Coronial inquests include evidence of how policing and medical institutions failed the deceased and contain recommendations for how to ensure these failures are not repeated. By including stack upon stack of coronial inquests into First Nations deaths in custody in Australia dating over more than 30 years, Archie highlights how these institutions continue to resist changes that could halt deaths.

Australia’s history is inextricably linked with the carceral system. British colonisation was established with penal colonies from 1788. Archie’s genealogy is illustrative of this, with his British and Scottish great-great-grandfather arriving as a convict in 1820; while his Kamilaroi and Bigambul great uncle was imprisoned in the notorious Boggo Road Gaol after accidentally killing his father during a fight over their paltry wages. Within the sea of coronial inquests, Archie incorporates archival records referencing his kin that evidence how vindictive laws and government policies have long been imposed upon First Nations peoples. These include reports by the Protector of Aboriginals denying his grandparents exemption from the Queensland Government’s Aboriginal Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897, and subsequent amendments that would have enabled them to access rights that non-Indigenous citizens enjoyed. Archie uses his family history to make the systemic issues imposed upon First Nations peoples uncomfortably tangible.

The reproduction of material about historical massacres where Archie’s family once lived and recent deaths in custody alone in kith and kin cannot carry the weight of the devastation to which they refer, and so Archie also turns to abstraction. The gaps in the paper records and moments of erasure in the chalk speak to incidents of physical destruction such as diseases, massacres and preventable deaths in custody; and to incidents of spiritual and psychic destruction including amnesia and the concerted efforts to efface people from the public record. The family tree’s black voids and severed branches reflect historic incidents, while the white lacuna at the centre of the room focuses audiences on fatal incidents within their lifetime and jurisdiction. The centre of the ceiling is also void of names; the artist notes that in Kamilaroi astronomy the Ancestors reside in the dark patches of sky between the stars. A cue that voids and abstraction do not necessarily signal the absence of life.

kith and kin is an extensive account of history – a vast abyss of time – yet it is a statement told from one point of view. The fragility of Archie’s perspective is reflected in the impermanence of chalk that could seemingly be wiped away without a trace. While his voice is singular, the vertiginous volume of names is confirmation that Archie’s position draws upon the knowledge of hundreds of thousands of his forebears. Archie’s white drawing on a black background resembles an astronomical chart and pays tribute to Kamilaroi astronomers. The artwork reaches into the deep time of space and simultaneously into the future through the suggestion of endlessly reproduced kinship connections. In the First Nations understanding of time, the past, present and future co-present. By placing 65,000+ years of family on a single continuum, kith and kin immerses audiences in the co-presence

of Ancestors and the co-existence of time, and by doing so Archie enfolds each of us into the everywhen.

Related people

Related information

Mīal by Archie Moore

In Gallery One

Previous exhibition, 2024Archie Moore is a celebrated Kamilaroi and Bigambul artist whose practice is embedded in the politics of identity, racism and language systems. Mīal is a conceptual self portrait that counters expectations of what a self portrait should be.

Portrait 71

Magazine

Ryan Presley about portraiture, Emma Kindred on the career of Joan Ross, Ellie Buttrose looks at Archie Moore’s kith and kin, and Joanna Gilmour steps into the world of Julie Rrap.

Embodiment of resistance

Magazine article by Behrouz Boochani

Kurdish-Iranian writer and filmmaker Behrouz Boochani on his portrait by Hoda Afshar, recently acquired by the National Portrait Gallery.