It’s the sort of image that makes you smile and shudder at the same time. Julie Rrap’s Overstepping (2001) is a square-format digital photograph depicting the artist’s calves and bare feet. Her toenails are painted red; the skin of her ankles is creased; and her heels are shaped like stilettos, as if her bones and flesh have morphed into an inbuilt, permanent pair of high-heeled shoes. It’s a work which prompts us to contemplate the cosmetic and surgical interventions women willingly submit to in conformity to the dictates of ‘beauty’ and fashion, and to imagine the grotesqueries that might ensue when this willingness remains unquestioned and unchecked. Rrap created the work having been invited to enter an art prize organised by a footwear company – who she assumes were expecting her to contribute a sculpture, not a two-dimensional work in which the sculpting has been effected by means of digital technology. Among the best-known of Rrap’s many works, Overstepping exemplifies signature features of her practice: the use of her own body to contest the depiction of women in art; her gleefully subversive appropriation and deconstruction of established codes in visual culture; and what art historian Ann Marsh has described as the ‘renegade experimentalism’ with which Rrap devises means of refining the incisiveness and wit embedded in her works. Portraiture, especially self portraiture, is another preoccupation, although not in the sense of seeking to show something about herself. Instead, for Rrap, portraits are a method of drawing attention to questions about the nature of looking and seeing, the function of representation, and the visibility – or invisibility – of women in the art world, especially as agents or creators. As she explained in 2023, ‘I’ve donated my body to the history of art as a kind of reflection on the fact that history can be very reductive and revisionist’.

Julie Rrap is one of the most influential artists of her generation, her career spanning five decades and encompassing performance, photography, installation, video and sculpture. Born in Lismore in northern New South Wales in 1950, she did a Bachelor of Arts at the University of Queensland from 1969 to 1971 and was influenced by the activism of the time, particularly feminism and the anti-Vietnam War movement. Her introduction to art came through working with her brother, the artist Mike Parr, on his performance works, and through her increasing engagement with other practitioners experimenting with concepts and techniques. At the same time, she perfected her skills as a photographer while running a business that specialised in photographing artworks for magazines and books. Her subsequent experience of living and working in Europe, she says, ‘really tested and proved my own inner drive to make art’.

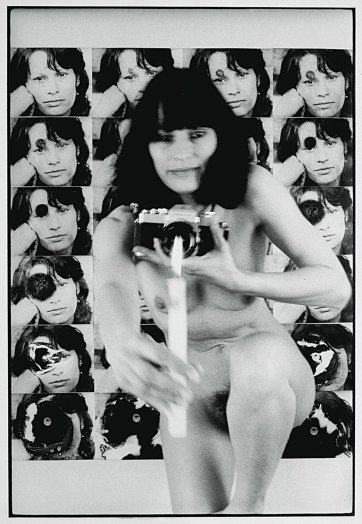

Her persistent curiosity about different mediums and processes – photography, performance, activism and what Rrap has called her ‘restlessness with materials’ – fused in Disclosures: A Photographic Construct, Rrap’s first major work, which also formed her first solo exhibition at Sydney’s Institute of Contemporary Art in 1982. A single-room installation, Disclosures included 60 individual black-and-white prints suspended from the ceiling to form two corridors. On one side of each row were portrait-format photographs of the artist, nude or nearly so, with a camera hanging from a strap around her neck. On the other, landscape-format photos showed Rrap in the act of capturing herself by simultaneously setting off two cameras – the one around her neck and one on a tripod on the opposite side of the studio. Disclosures examines voyeurism, the objectification of women’s bodies, and the power imbalance inherent in the act of looking. Yet in making viewers experience the work by walking between the rows of mirrored images, Rrap constructs a sense of how it feels to have lenses trained on you from both sides – to be the viewed rather than the viewer – making it ‘a work about what photography does to a subject,’ she says, and specifically about what the camera does when it is pointed at a naked female body. In this way, Disclosures also speaks to another characteristic Rrap has subsequently observed of her practice – that of ‘feeling the need to engage the audience very directly, almost as performers themselves in the work’.