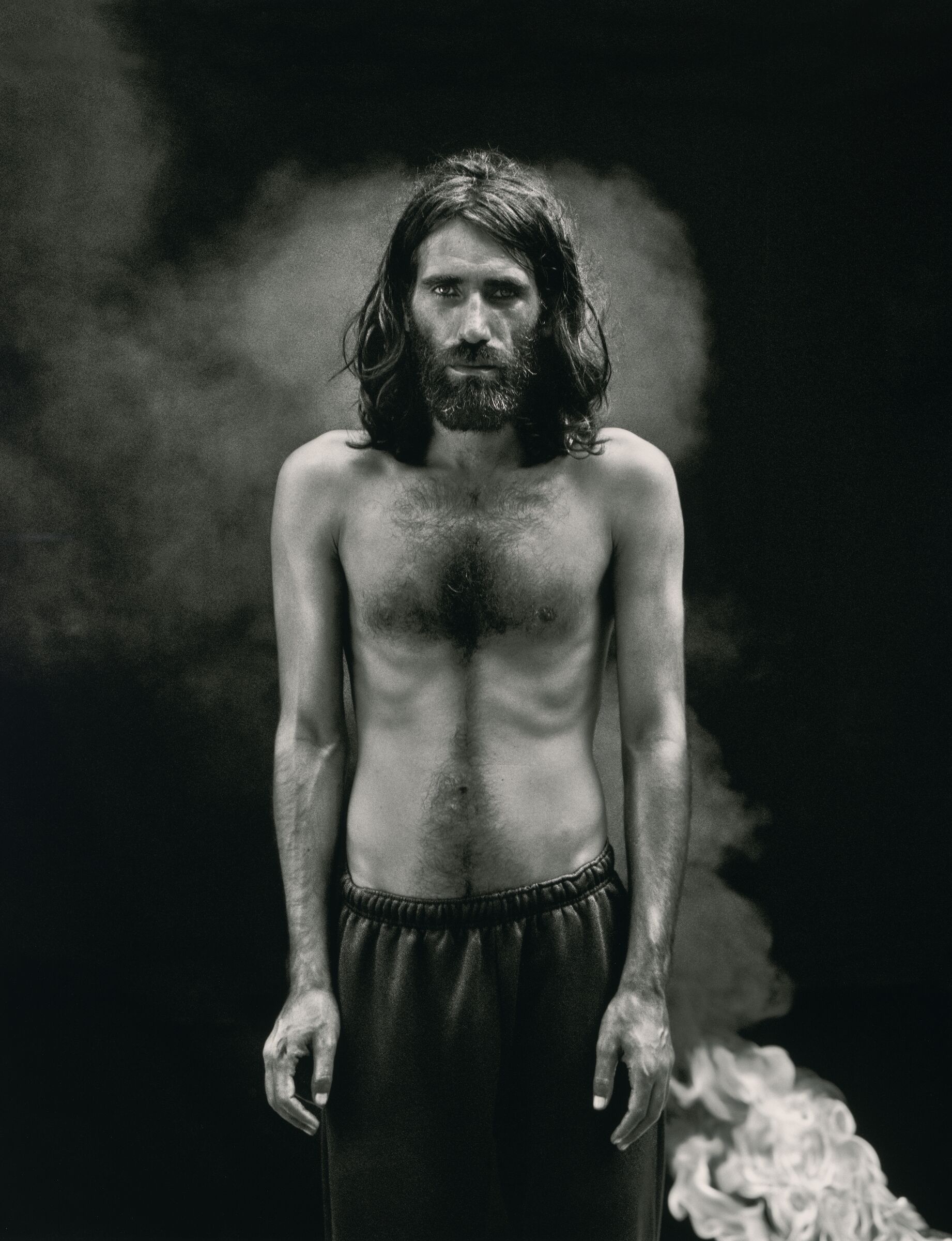

I first stood before Hoda Afshar’s camera five years ago on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea. I was still in indefinite detention, one of the many hundreds of men caught up in Australia’s asylum-seeker system. Hoda had made her way to Manus Island in secret to create a new body of work with us. It was a hot day – even hotter than usual – and a small group of us had snuck into the forest to avoid being seen by the guards. Hidden from their view, we created a series of images which were to become the work Remain (2018), including a portrait of me that has had an interesting journey in the years since. Five years after that photograph was taken I finally stepped onto Australian soil, and for the first time I saw it, up close and in person, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney.

I confess that this experience was harder than I had expected. I secretly wished everyone out of the gallery – the crowd that had gathered around us, the journalists, and even Hoda – so that I could be alone with that photograph. I had seen it countless times in newspapers and on computer screens, but here it was something else. I felt the weight of the image for the first time; the weight of my own gaze cast upon me from the gallery wall. I stared at my cement-like pallor; at the bulging veins of my hands; at my ribcage, which seemed to stick out through my skin. I tried to recall what I was thinking about when Hoda took the photograph. I remembered feeling that eventually we would triumph over the system that had banished us to that island, we refugees with our frail, half-naked bodies.

When I talked about this portrait with Hoda before that gallery visit, I told her that it used to scare me. It embodied a moment in history when a naked, homeless man with empty hands stood up against a system. But when I was standing in front of the photograph that fear was gone. I found it glorious and mysterious. And as the subject of this picture, I felt more strongly than ever the artist’s urge to challenge the common perception of refugees as victims.

Shifting the dominant ways of seeing is a central preoccupation of Hoda’s work, and it is what distinguishes her practice, I believe, from the usual approach of documentary photography, which all too often simply reproduces the image of refugees and other marginalised figures as powerless victims because of the unequal power relation between the photographer and the subject. In such images, the camera becomes a weapon that targets the refugee and inflicts a fresh wound on his body to produce a sense of pity or sympathy in the viewer. Depicted as if lacking his own will or individuality and incapable of demonstrating complex feelings or aspirations for autonomy, the refugee is denuded of his identity by the camera.

In Hoda’s work, by contrast, the subject is invited behind the camera and becomes an active collaborator in the process of the image’s creation. Here, there is a bond between the photographer and her subject that generates trust. Here, the camera is not a weapon but a tool that the artist wields to open up space for the subject, allowing them to express their identity, their desire, their narrative. So it was that in the process of making Remain, Hoda gave us the freedom to appear before the camera as we wanted to be seen. We were allowed to sing or laugh or walk in the forest or on the beach and play with the sand.

We were allowed to present ourselves however we wanted and articulate our stories as we saw fit. Thus the work incorporates performances, songs, historical references and human emotions, and tackles topics such as death, forgetting and nature – elements that are all but absent in most works that adopt the dominant journalistic approach to picturing the plight of refugees.

The value of Remain lies in how it conveys the narratives of a few of us who were trapped on Manus Island. Also important is its portrayal of humans violently expelled from the human community, of contemporary individuals reduced to bare existence.

In Hoda’s portraits these excommunicated people gaze back at the viewer, not just with their eyes but with flesh and bone, with their ribcages sticking out through their skin, and silently shouting, ‘Look at me, here I am, I am human too.’ In this respect, the work has a strong historical significance, as it forces us to confront a part of Australia’s recent history that had been kept hidden, a period in which the Australian Government, for purely political reasons, banished thousands of innocent people to offshore immigration detention camps and systematically punished them for years.

This is an extract from Behrouz Boochani’s ‘Embodiment of resistance’, translated by Amir Ahmadi Arian, in Isobel Parker Philip, ‘Hoda Afshar: A curve is a broken line’, published by the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2023. Text © Behrouz Boochani.

پنج سال از روزی که روبه روی دوربین هدا افشار ایستادم می گذرد. در آن زمان من یکی از چندصد پناهنده ی گرفتار در جزیره ی مانوس بودم که در مسیر پناهندگی به استرالیا از آن جا سر درآوردیم. هدا مخفیانه به جزیره آمده بود تا روی پروژه ای با ما کار کند. در روزی ب ینهایت گرم به دور از چشم نیروهای گارد استرالیایی به داخل یکی از جنگ لهای جزیره مانوس خزیدیم. دور از چشم نگهبانان کمپ او پرتره ای از من گرفت که بخشی از شد و بعدها به سرانجامی جالب رسید. بعد از پنج سال در سفری دراماتیک بالاخره پایم به خاک Remain پروژ هی استرالیا رسید و پرتره را در موزه هنرهای مدرن استرالیا در شهر سیدنی برای اولین بار دیدم.

اعتراف میکنم رویارویی با این پرتره برایم سخت تر از آن بود که انتظار داشتم. احساس می کردم باید تنها باشم. دوست داشتم تمام آدمهای داخل گالری به اضافه عکاس های روزنامه از آنجا خارج شوند, حتی هدا به عنوان خالق پرتره که کنارم ایستاده بود، دوست داشتم او هم از آنجا برود. سال ها آن تصویر را فقط در روزنامه ها و سای تهای آنلاین دیده بودم. حالا روبه رویش ایستاده بودم, به رنگ سیمانی اش, به چشم ها, به رگ های باد کرده روی انگشتها, و به دنده های برآمده و قامت استخوانی اش نگاه می کردم . وقتی هدا این پرتره را ازم گرفت دقیقا نمی دانم به چه فکر می کردم اما احساس آن روزهایم این بود که بالاخره روزی فرا می رسد که ما پناهنده ها با این بدن های نیمه لخت بر سیستمی که ما را برای سال ها در تبعید شکنجه می کرد پیروز خواهیم شد.

پیش از آغاز نمایشگاه، اولین بار که پرتره را دیدم، به هدا گفته بودم که من از این پرتره می ترسم, چون نماینده نقطه ای از تاریخ است که انسانی با بدنی نیمه لخت که به مکانی دور پرت شده است حالا در برابر سیستم قد علم کرده است, اما حالا از آن نمی ترسیدم. به نظرم پرتره شکوهمند بود، رازآلود و شگفت انگیز.

به عنوان سوژه ی این کار آن چه برایم مهم است فاصله گرفتن هدا از نگاه غالب رسانه ها و هنرمندانی ست که تمایل شدیدی به قربانی سازی از پناهنده ها دارند، دیدگاهی که در آن پناهنده موجودی ست منفعل، قربانی چیزی فراتر از Remain و بی هویت که حق ندارد کنشگر باشد. برای من این پرتره به همراه ویدئو اینستالیشن داستانی شخصی ست. رویکرد هدا به این موضوع متفاوت از دیگر هنرمندان بود. قبل از اینکه به جزیره مانوس برود چندین ماه به شکل فشرده مطالعه کرد، بعد به مدت دو هفته با چند نفر از پناهنده ها و از جمله من زندگی کرد و در ادامه از ما خواست که در یک پروژه عکاسی و ساخت فیلم با او همکاری کنیم. در ادامه آتشی برپا کردیم، مشارکت کردیم. Remain دود راه انداختیم و در فضای دوستانه ای در پروژه خلاقانه دیدگاهی که اغلب مایل است پناهنده ها و یا گروه های اقلیت را به عنوان یک سوژه بی دفاع، مطلقا منفعل و فاقد هر نوع قدرت به تصویر بکشد, عکاسان و هنرمندان را مسلط بر بدن پناهنده می خواهد. رابطه عکاس و سوژه او مطلقا یک طرفه است و دوربین در جایگاه اسلحه قرار دارد، به طرف سوژه نشانه گیری می کند و تصویری از پناهنده م یگیرد که بتواند حجم زیادی از دلسوزی را متوجه او کند. در واقع سوژه، یعنی پناهنده ، در این نوع نگاه یک موجود فاقد اراده، فاقد فردیت، فاقد پیچیدگی های انسانی، قدرت و استقلال فردی ست. دوربین به طور کلی در جهت هویت زدایی و فردی تزدایی از سوژه ها که همان پناهنده ها باشند عمل می کند. اما در پرتره ها و ویدیو اینستالیشن هدا روایتی بر خلاف تصویر تثبیت شده و تکراری همیشگی از پناهنده ها ثبت شده است. در این کار نه تنها سوژه منفعل نیست بلکه خودش در جریان خلق این کار فعال است، خود بخشی از جریان خلق ما می توانیم Remain است و حتی می توان گفت خالق است. در این پرتره ها و به خصوص ویدیو اینستالیشن آتش را ببینیم، دود را ببینیم و مشخص است که شبیه صحنه ای از یک نمایش کاملا فضاسازی شده است. آنچه برای او مهم است خلق کردن زبان جدیدی از هنر است که در چارچوب زبان استعماری و منظومه های فکری استعمارگرایی نباشد.

در کارهای هدا یک نوع اعتماد عمیق بین عکاس و سوژه برقرار است که در نهایت به خلق این تصاویر ختم شده است. این البته صرفا اعتمادی اخلاقی نیست و یک نوع اعتماد عمیق سوژه به تفکر و نوع نگاه هنری عکاس است. در این پروژه دوربین نه تنها اسلحه نیست بلکه ابزاری ست که فضایی را ایجاد می کند که سوژه می تواند پناهنده ها کاملا آزاد هستند که آواز بخوانند، شعر بگویند، Remain هویت، فردیت و شخصیتش را آشکار کند. در بخندند و یا اینکه در جنگل و ساحل راه بروند و با شن ها بازی کنند. آن ها کاملا آزاد هستند که خودشان را و داستان شان را آنگونه که دوست دارند عرضه کنند و عکاس و یا فیلمبردار در جایگاه دیکته کردن و تصمیم گیری نیست. این دقیقا نگاهی ست که در ژورنالیسم سطحی، سازمان های حقوق بشری و بسیاری از هنرمندانی که درباره موضوع پناهندگی و یا حقوق اقلیت ها کار م یکنند غایب است.

هدا افشار آشکارا در پی ایجاد یک زبان و نگاه جدید به پناهنده به عنوان یک انسان است. هر چند کارهای او تکان دهنده هستند، این مساله به خود پناهنده ها بر نمی گردد بلکه تصاویری که او خلق می کند تصویر لخت انسان معاصر است. تصاویر او می توانند نماد انسانی باشند که به بی رحمانه ترین و وحشیانه ترین حالت از جامعه انسانی طرد شده است. انسانی که با نگاهش ، با بدن و استخوان ها و دنده های لاغرش به جامعه انسانی نگاه می کند و می گوید "من هم انسان ام"، می گوید "این منم با تمام پیچیدگی های انسانی ام".

از این منظر،این اثر نقشی تاریخی و کلیدی دارد, چرا که ما را مجبور میکند که با بخش تاریکی از تاریخ معاصراسترالیا که از انظار عمومی پنهان شده بود مواجه شویم. دورانی که در آن دولت استرالیا چند هزار نفر انسان بی گناه را به دلایل منافع سیاسی و قدرت طلبی به جزایر نارو و مانوس تبعید می کند و برای سال ها تحت شکنجه سیستماتیک قرار می دهد. اهمیت این تصاویر با گذر زمان بیشتر معنا پیدا می کند