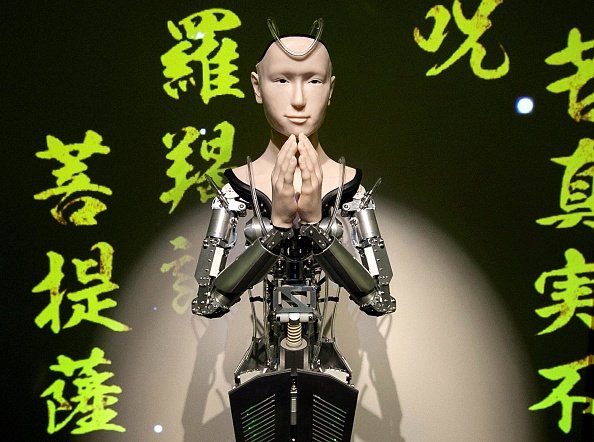

Human-like robots provoke unsettling feelings of familiarity crossed with unease and sometimes revulsion. The ‘uncanny valley’ (bukimi no tani), coined by Japanese roboticist Professor Masahiro Mori in 1970, essentially describes the relationship between an object’s degree of resemblance to a human being and an observer’s emotional response to the object. As Professor Mori wrote, ‘We should begin to build an accurate map of the uncanny valley, so that through robotics research we can come to understand what makes us human.’ Anyone who is familiar with the Netflix hit series, Black Mirror, or has encountered one of Australian artist Patricia Piccinini’s hyper-real sculptures, will have experienced the feeling of blundering into the uncanny valley.

These humanoid robots can be viewed as a kind of portrait; of humanity, of our desire to relate to each other, and of scientific discovery. This brave new world of technological advancement is pushing the boundaries of portraiture, and indeed art, as we know it. Let’s consider what the future might hold by taking an experimental journey into the weird, wired world of the post-human.

Transhumanists have long speculated that technological developments will bring about a kind of digital utopia whereby humans are able to live on after death. In 2023, with the evolution of artificial intelligence, blockchain and the proliferation of social media use, it is now possible to imagine a future where we can create new forms of posthumous digital presences. The rapid evolution of chatbots such as Project December, ChatGPT or Google’s recently announced Bard project can emulate the style of whatever text is fed to it. Through learning from the preserved remnants of our digital trails – emails, text messages, social media interactions, voice recognition software, voicemail, photos and video recordings – AI can enable a digital presence to ‘talk’ in a way that mimics someone who is no longer with us. Not only will our presence be preserved, but it has the potential to replicate and continue to evolve after we die.