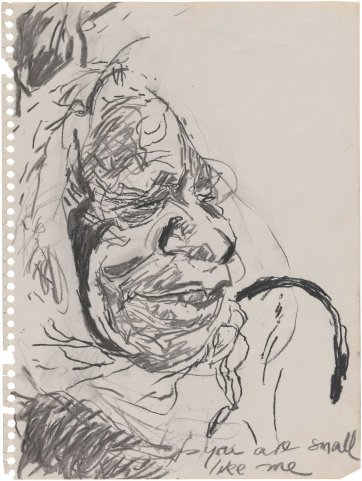

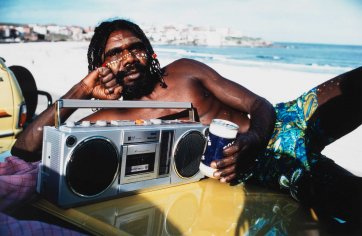

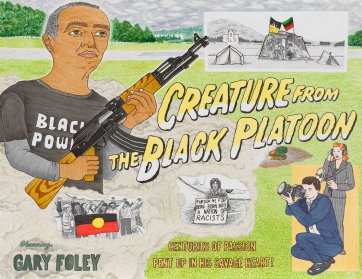

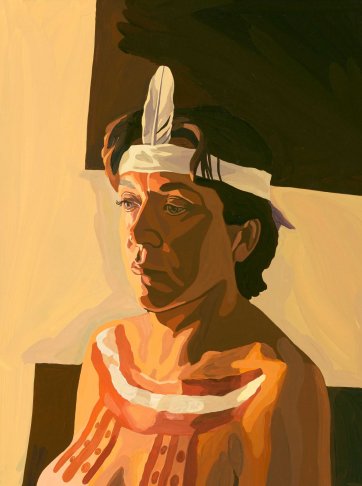

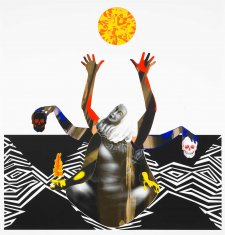

Of the first seven works acquired by the National Portrait Gallery of Australia on 27 May 1998, none were pictures of people who were powerful or beautiful or filthy rich, and there wasn’t a prime minister or a monarch or a Test cricketer in sight. Their subjects were artists, a satirist, a vaudevillian, a musician and a trade unionist. Two of them depicted women and were painted by a woman, and there was one which some would struggle to describe as a portrait at all. All of them were gifts to the Gallery with one exception: a shimmering depiction of Anmatyerre artist Emily Kame Kngwarreye, painted by Jenny Sages in 1993. Should proof be needed that Australia’s National Portrait Gallery was never conceived of as a place for the veneration of staid paintings of (or by) dead white males, Sages’ Emily Kame Kngwarreye with Lily is it.

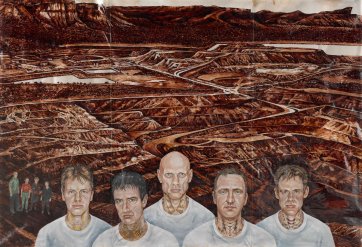

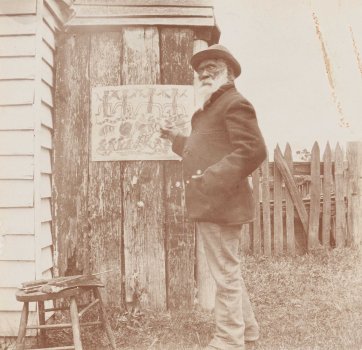

From its outset, it was clear that the National Portrait Gallery would be a very different institution to the one painter Tom Roberts envisioned at the start of the twentieth century, when he wrote to then Prime Minister Alfred Deakin to encourage the idea of establishing a portrait gallery along the lines of the example founded in London in 1856. Referring to the Australian Parliament in a letter to Deakin in March 1910, Roberts said ‘it disturbs me to think that most of you are likely to go on till the inevitable comes, and leave behind nothing that will give the future anything that will show what you all were as men to look at.’ Implicit in Roberts’ phrase are a number of the concepts underpinning the establishment of NPG London – such as the notion that portraits served a memorialising, reverential purpose, and that qualities such as courage, foresight and leadership (associated only with men, evidently) could be discerned from the accurate transcription of an individual’s outward appearance. In forming our own collection of portraits of those whose lives and stories make them notable or memorable, Gallery curators have of course remained cognisant of these traditional, historical aspects of portraiture. Indeed, for the first 20 years of its life, the Gallery’s permanent displays presented the collection in chronological order, linking us to our handful of international counterparts through what inaugural NPG Director Andrew Sayers called the ‘belief that portraits illuminate history; and that a continuous display of portraits, embracing the historical and contemporary, helps us to understand the way in which individuals have shaped and continue to shape our national identities’.

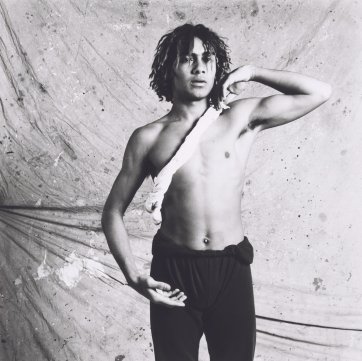

Equally, however, the collection has always sought to highlight the question of how artists, in their innumerable and unique ways, convey a sense of a sitter’s story. While the Gallery has embraced the concepts of historical significance, likeness and authenticity as criteria for the inclusion of portraits in the collection, it has also foregrounded that Australia is home to ancient First Nations traditions in which identity is not necessarily defined by appearance but by relationships to people, to the past and to place. The equal weight accorded to artist and subject, along with the adaptability of the collecting framework, has supplied a formula for the creation of a diverse and textured collection that enables the Gallery to present a national story that reads, as Sayers once phrased it, ‘like a tapestry, rather than a tombstone’. In this respect, Jenny Sages’ painting of Kngwarreye and other foundational acquisitions set the tone for the building of a collection that continues to test the flexibility and sophistication of what is often perceived as an unbending, narrow field of visual arts practice.