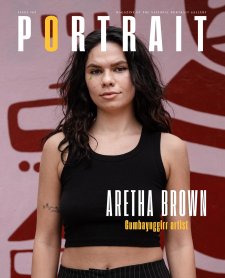

Wrapped around the construction hoarding of Melbourne’s Collins Arch precinct, Aretha Brown’s 190-metre mural honours the late Uncle Jack Charles and celebrates First Nations history, knowledge and empowerment. Painted in her signature playful graphic style of figures and symbols, it’s difficult to miss. But then Aretha has never been afraid to make her presence known.

Born and raised on Wurundjeri Country, Aretha made a speech at the 2017 Invasion Day rallies in Melbourne to an estimated 50,000 protesters – at the age of 16. She was the youngest ever Prime Minister of the National Indigenous Youth Parliament, and her first painting, Time is on our side, You Mob, was selected for the 2019 Top Arts exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria while she was still at school.

Now 22, Aretha is well-known for her large-scale public murals (53 so far). Together with her team of young women and non-binary artists – the Kiss My Art Collective – she has painted murals on walls, hoardings and shipping containers across the world, from Melbourne and Sydney to the UK, India and Indonesia.