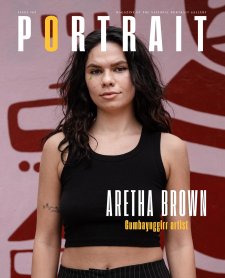

The Archibald Prize. A century. Over 6000 works and 1500 artists. Where do I start!

In 2018, as the honour – and enormity – of curating an exhibition tracing the history of Australia’s most beloved portrait award finally dawned on me, the herculean job of tracking down that vast number of past works from which a selection of paintings from across the decades would be brought together for Archie 100: A Century of the Archibald Prize began. The Archie 100 project team – comprising myself, assistant curator Ciara Derkenne and online producer Kirsten Tilgals – started writing emails. Lots of emails. We contacted institutions, both public and private, across Australia and further afield to find out what portraits they held in their collections: art galleries, museums, libraries, schools, universities, churches, sporting organisations, town halls and the many agencies of government. Of course, there were the artists and their families, as well as the subjects of Archibald portraits and their families.

Many people assume, understandably, that every work that has appeared in the Archibald Prize must have been documented and photographed. Yet it is only relatively recently, in a digital age, that this has been possible. Not even a list of works survives for the inaugural 1921 Archibald Prize, and that first exhibition, held in January 1922, garnered little interest in the press. We’ve been able to determine there were 41 works, and identify many of them, from scant records kept in the Art Gallery’s archives and a few newspaper reviews. In the years that followed, the winning work was always reproduced in the press, but little else.

For the first few decades, artists were able to submit as many works as they wished, and all entries were displayed. Then the rules changed. With nearly 200 Archibald portraits lining the Gallery’s walls in 1945, the Trustees declared that, from 1946, a selection of works would be made for exhibition. Artists could enter just two works, with both portraits eligible for selection. In 2003, this was reduced to one work. Even knowing the details of the paintings in the prize, we rarely knew what happened to them after they were exhibited – not even the winners (the prize is not acquisitive). Some have found their way into public collecting institutions, but the vast majority are in private hands, with their current owners often unaware of the work’s history.